English PhD student Aaron Bartels–Swindells played a lot of rugby and basketball growing up. When he was a child he had three teeth knocked out during a game. He got them replaced, and he was fine.

But when Aaron, who is now 28, was in his second year at Penn, he went for a dental checkup and discovered that his teeth were breaking down. They needed to be extracted and replaced immediately before painful abscesses or root damage occurred.

Aaron was enrolled in the Penn Dental Plan, which he thought would fund the procedure. But he found out its annual coverage of $1,500 was not enough for the surgery—he was about $3,000 short.

He scrambled to save $3,000 in the two months before the dental plan expired. He was working as a Graduate Advisor in Harrison to save money—the University does not pay GAs a wage, but the position meant he didn’t have to pay rent and had a partial meal plan. Even so, “it just wasn’t possible” to save up so much money in such a short period.

Two and a half years later, he still hasn’t had the procedure.

“I could show you the parts of the tooth that are breaking down,” he half–joked. “It’s quite noticeable. It’s sort of shedding, ever so slowly.”

For Clint Williamson, English PhD student and member of GET–UP, Penn’s graduate student union, the foremost benefit of unionization is “the ability to combat precarity,” so that students with medical problems even more urgent than Aaron’s can have some reassurance about their health while trying to earn their degree.

“You have people doing very large amounts of work...but making what amounts in many cases to poverty level wages,” Clint said. “They’re one emergency away from not being able to continue with work, not being able to pay their bills, being potentially evicted.”

Graduate students at Penn live off stipends and sometimes grants, but students rarely finish their degrees before their fixed stipends run out. Sudden medical emergencies can drastically delay their academic careers. They work as teaching assistants—and sometimes even instructors—on top of rigorous course loads. But they don’t have a contract of employment, so Penn can can change their working conditions and give or take away benefits whenever it wants.

Last year, a group of students revived GET–UP, a group that tried and failed to form a graduate student union over a decade ago. The new GET–UP rallied support and brought their cause to the National Labor Relations Board to decide whether they could form a union. On December 19, after months of legal rebuttals from Penn, the board granted GET–UP the right to hold an election. This spring, Penn graduate students will vote if they want to unionize. If they do, and if Penn recognizes the vote, they will be legal employees of the University with the right to contracts of employment, collective bargaining, and “a seat at the table”.

Making ends meet from 3,000 miles away

Over the phone from California, graduate student Victoria Gill breaks off mid–sentence to address the squealing noises in the background of the call.

She apologizes, laughing. “Sorry, I just had the baby,” she says. “One second.”

Though she’s still in her third year at Penn’s Graduate School of Education, Victoria moved to California when she got pregnant. Because Victoria is earning a Doctor of Education degree, she receives less funding than her PhD counterparts, though both are doctoral degrees in the Graduate School of Education.

While living in California with her partner makes sense financially, it comes at a cost for Victoria. She can afford to take care of her child, but she’s 3,000 miles away from her colleagues and Penn’s campus.

“Graduate students are not just students, we’re also workers,” Victoria says. “We’re TAs, we work at Weingarten, we work at the Writing Center, we work at different offices on campus. We’re working to have our voices heard so that our conditions are fair and livable.”

GET–UP stages a 'work–in' and calls on Gutmann to 'protect' them from the GOP tax bill in November 2017.

Unlike many of her peers, anthropology and GSE PhD student and GET–UP organizer Miranda Weinberg has not had major funding issues, problems with advisors or other superiors, or suffered from severe medical problems.

Miranda remembers a friend in her program who contracted tendonitis from the typing–heavy coursework required of graduate students. It was severe enough that he had to take a leave of absence to recover—but since he was on leave, he lost his Penn health insurance.

“Right now they sort of hold your fate in their hands, and so it ends up being about luck. I’ve been lucky,” she says, “but I don’t think you should have to be lucky.”

Graphic by Alana Shukovsky

An administrative cold shoulder

Victoria is a member of GET–UP, Penn’s graduate student union. She shares the belief—along with an increasing number of her peers—that her issues with the University will be solved by forming a graduate student union.

GET–UP, short for Graduate Employees Together at the University of Pennsylvania, was formed in the fall of 2000. In 2003, GET–UP held an election for Penn graduate students, and according to DP exit polls from that day, a majority voted to unionize. But the results were never released—Penn petitioned to have the ballots impounded.

Current GET–UP members have already noticed parallels between the current Penn administration’s behavior and that of the administration that quashed unionization in the 2000s. They’re worried there might be a repeat of history.

The morning after this spring’s election was announced, the administration sent out an email, signed by Provost Wendell Pritchett, urging students not to support unionization, noting that a union “would in fact be counterproductive to the goals for graduate student success that we all share.”

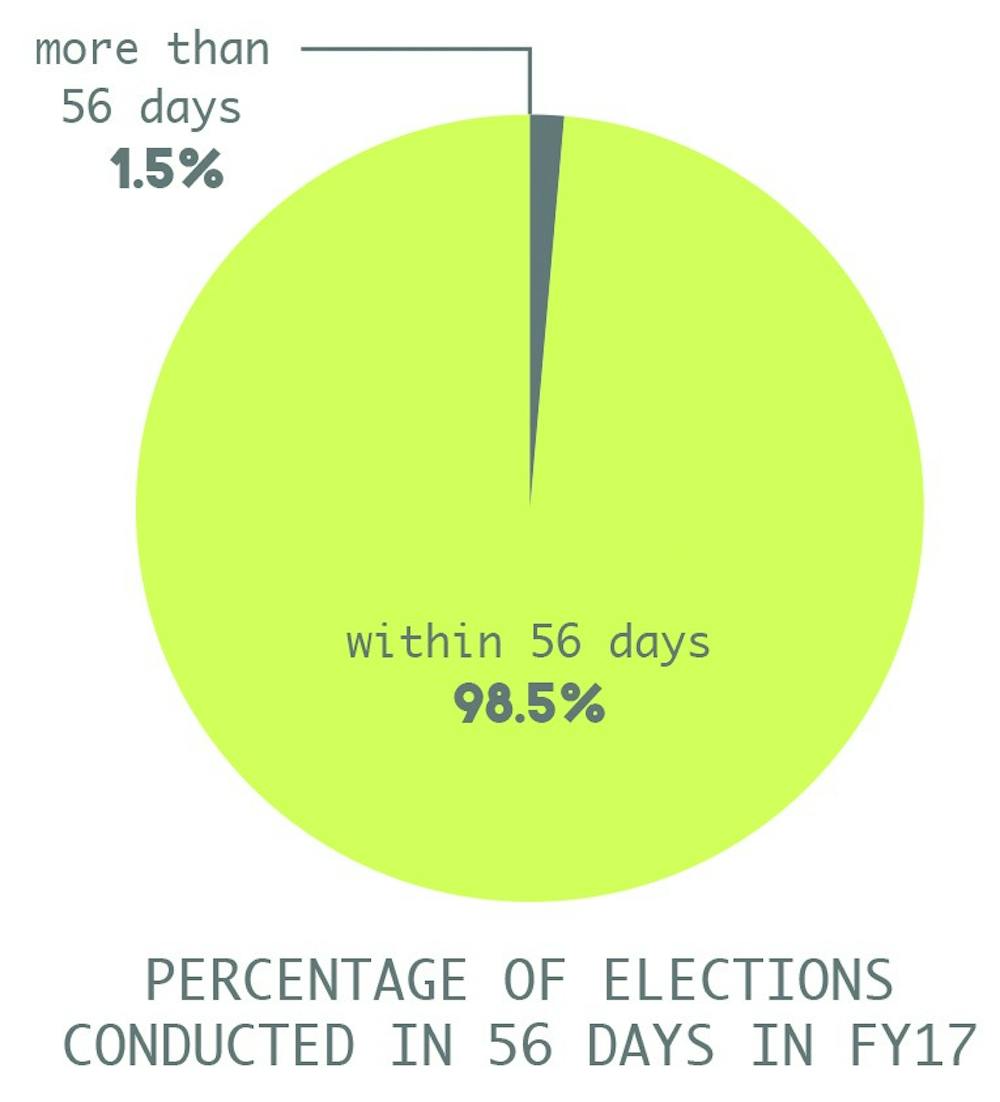

Graphic by Alana Shukovsky

Miranda points out that numerous Penn faculty had signed a letter in support of unionization.

The Provost also wrote, “President Gutmann and I believe strongly that graduate students are our students, mentees, and future colleagues rather than our employees.”

Some students agree with the administration’s opposition.Shortly after GET–UP went public, a counter–group formed: “No Penn Union.” They believe a single union representing several graduate schools would be detrimental to some schools.

On their website, No Penn Union cites signatures from 550 PhD students who oppose unionization. No Penn Union member Ian Henrich, a PhD student in Biomedical Graduate Studies, says in an email that many students in his school are happy with how it’s run and “don’t want a barrier between them and the [BGS] administration.”

He notes that he and other friends are also turned off by GET–UP’s aggressive recruitment tactics and concerned that strikes might interrupt students’ research,possibly delaying their graduation time.

These experiences have caused him to “completely lose faith” in GET–UP’s ability to run a union.

Graphic by Alana Shukovsky

Small reward, big risk

After GET–UP went public, Aaron notes, Penn announced three things: it was going to increase funding for graduate students with families, reduce the annual cost of the dental plan from around $400 to $200, and provide free gym membership for graduate students. Aaron believes that Penn has tried to quell support for unionization by offering material benefits to students.

Aaron views this as an attempt to “buy the support of PhD students against unionization.”

Miranda also noticed the peculiar timing and sudden arrival of the extra benefits: “[The Graduate and Professional Student Assembly] has been asking for free gym access for years, and we were given it last year, coincidentally right after GET–UP became a public campaign.”

Penn alum and former GET–UP organizer Joanna Kempner remembers Penn deploying similar tactics during the push for unionization in the early 2000s. When Kempner started at Penn in 1998, health insurance was not available to graduate students. After GET–UP was formed in 2000 and then started gaining traction, Penn “suddenly provided health insurance” and “significantly” increased stipends.

“You know, that’s great, but the cynical part of me thinks of that as a union–busting tactic.” Kempner says. “Those advances didn’t occur until [we] began to organize and apply pressure on the administration.”

Miranda says that although these benefits are “great,” they also display the gross imbalance of power that exists between Penn and its graduate students. A union, Miranda says, would obligate Penn to consult with students on the kinds of benefits they receive, instead of deciding for them. The lack of discourse can also lead to policies that aim to improve students’ lives, but actually fail to do so.

Referring to the dental plan, Aaron remarks that even though Penn provided a 50% discount for it, the cap for the actual insurance still stood at $1500, and so was not able to help him afford his procedure.

“On closer inspection, it didn’t change anything,” Aaron said. “It’s still not a plan that’s designed to cover dental emergencies.”

An even more worrying aspect to this is if the University can dole out gym memberships and dental plans without warning, then the reverse is true, too. “Maybe five years from now they’ll decide to stop [providing the benefits]. The advantage of a contract is we can say, ‘no, this is really important to grads, and it needs to be written down that we can have this,’” Miranda said. “[Otherwise] the same way that it’s given to us, it could be taken away.”

The puppet in College Hall

On February 27, 2007, roughly 55 GET–UP supporters trudged through the snow from 40th Street to College Green. They crowded outside College Hall, which houses Amy Gutmann’s office, chanting “Amy, don’t you run away, listen to what we have to say!” They were armed with a ten–foot–tall puppet—a terrifying caricature of Gutmann with giant reddish fists, a grimacing papier–mâché face, and billowing strips of yellow paper hair. The protest was not successful.

2007 GET–UP activists with a puppet of Gutmann. Photo courtesy of Stefan Heumann.

GET–UP staged the protest in an attempt to convince Gutmann to meet with them and discuss their demands, something she had promised to do in a letter she wrote to GET–UP when she was a Princeton professor. 2009 graduate Stefan Heumann, who was in GET–UP while earning his PhD, remembers the atmosphere of optimism among GET–UP activists when Gutmann became Penn’s president in 2004. They thought Gutmann’s influence might “change or at least soften [Penn’s anti–union stance], so that dialogue would become possible.”

Ten years later, Gutmann has still never met with the group, and GET–UP still sees Gutmann as the primary emblem of the administration’s hypocrisy.

“We decided to make a puppet of Amy Gutmann and symbolically chase her across campus, as she was cowardly, always running away from us instead of engaging,” Heumann recalled in an email.

As president, Gutmann has discouraged support for GET–UP on the grounds that a union would “adversely affect both current students and faculty members, and future students for years to come.”

“To this day, I remain very disappointed in her behavior and poor leadership,” Heumann, who is now co–director of a Berlin think tank, wrote. “We knew that getting her to drop the University’s opposition to our union would be hard, but she could have at least mustered the courage to talk to us.”

“With a president like Amy Gutmann who values deliberative democracy so much, I would expect that she would like to sit down and deliberate with us,” Zach said. “There’s nothing more we’d like.”

Zach, Clint, Miranda, Victoria, and Aaron all express hope that Penn’s administration will do what it has not done in the past: recognize the election results if students vote for a union and sit down with GET–UP to negotiate their employment.

But to observe Penn’s historical precedent is to observe an unwavering opposition to unionization.

“The University doesn’t want to give up power, and why would you?” Zach says. “You’ve got 100% say over the working conditions and wages and benefits of your employees—why would you want to give that up?”