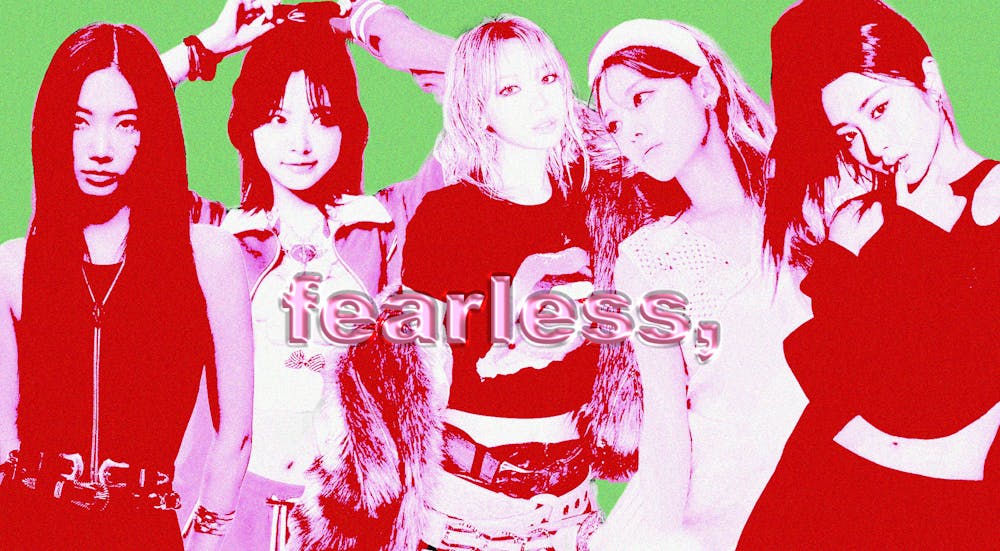

“LE SSERAFIM - SATURDAYS, COACHELLA.” In the billboard announcing their upcoming set at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, the members of the K–Pop girl group LE SSERAFIM are positively aglow: hair swept, gazes confident, skin sculpted. The day before their set, frontwoman Yunjin posts a photo of the group on Instagram posing with the announcement, Hilary Duff's “What Dreams Are Made Of” playing in the background. It is the youngest K–Pop group to clinch a set at the lauded Indio, Calif. music festival a mere two years after its debut; the members are excited, ready to mark a significant milestone in their artistic career.

What followed their performance rapidly took a turn for the worse.

The group performed a setlist of ten songs, ranging from popular hits “ANTIFRAGILE” and “FEARLESS” to punchy live–band renditions of “Fire in the belly” and “Eve, Psyche & the Bluebeard’s wife.” As videos of its set began to circulate online, however, LE SSERAFIM found itself under fire for poor performance quality. In particular, discourse first expressed disappointment at the members' perceived lack of vocal control and pitch stability, then outright resentment towards the group as a whole.

In the months that followed, what began as one–time criticism spiraled into what became known as the “LE SSERAFIM hate train”: a monthslong stream of negative comments, threats, and attacks on the group based on its perceived lack of talent and undeserved popularity. LE SSERAFIM member Sakura released a personal statement sharing she was proud of her members regardless of the negative reception of their set. But, this PR move did little to stop momentum as the movement roared forward—all members were forced to turn off the comments on their Instagram posts. They were certainly not the first artists to deliver an underwhelming performance, nor were they the first to make a musical blunder at Coachella. So why did LE SSERAFIM become the target of such extensive, all–consuming criticism?

At its core, the underlying themes of the backlash have nothing to do with the actual performance itself. Rather, LE SSERAFIM’s Coachella controversy reveals the tenuous position young female artists hold in the K–Pop industry, which still exists in the context of patriarchal norms.

Modern cultural discourse often characterizes K–Pop as emphasizing mass appeal and cookie–cutter production, but we dedicate less discussion to what this means for the idols themselves: in particular, young women and girls. Girl groups have and continue to hold up a significant portion of the K–Pop industry, from Girls’ Generation in the 2010s to the likes of LE SSERAFIM and aespa today. However, the young women in these groups also face unique pressures that lay bare the nebulous line between the gender dynamics and popular culture dominating K–Pop.

We can see this most clearly when thinking about cultural capital—the social assets that are associated with social mobility within a culture. Notoriously, society regards young women as a demographic that lacks cultural capital, our interests often disregarded or belittled as childish and shallow. This notion appeals not just to consumers of culture, but also to its creators. As young Asian women—no matter how successful they are—girl group idols are equally subject to the scrutiny of patriarchal norms attempting to undermine their platforms. The cultural space they’ve staked as artists and celebrities is tenuous and temporal; their abilities are quick to be called into question, and these questions are quick to turn into claims that they are unworthy.

In July, LE SSERAFIM released a five–part YouTube documentary titled “Make It Look Easy,” a nod to its title track "EASY" released in February—which was seen by many as a response to the negative reception of the group since its Coachella performance in April. Even the first episode alone—a short and sweet 20–minute assortment of the members’ fast–paced, glittery lives interspersed with carefully constructed vignettes of candid, emotional conversations—reads almost as a determined plea to justify their success. From shots of Eunchae hyperventilating midperformance to a segment of Chaewon taking an IV drip in order to finish a music video shoot while sick, the series appeared less like the fare typical of artist documentaries and more like an attempt to subtly justify the girls as worthy of their own careers.

In their one–of–a–kind musical and visual universe, LE SSERAFIM embodies themes of self–confidence and energy, much like the images of the members glowing on their Coachella billboard. Underneath this feel–good image, however, the Coachella controversy serves as a reflection of the tenuous space held by female idols in their own careers as young women in a patriarchal industry. In the middle of the first episode of “Make It Look Easy,” Yunjin discusses her career alone in her studio. “There’s an end to everything, right? I’m already afraid of the end.” It’s a common trope, the celebrity discussing the temporary nature of their own spotlight. As Yunjin looks pensively into the camera, however, I am reminded that she is just four years older than I am; yet for young women like her, some endings feel a lot more immediate than others.