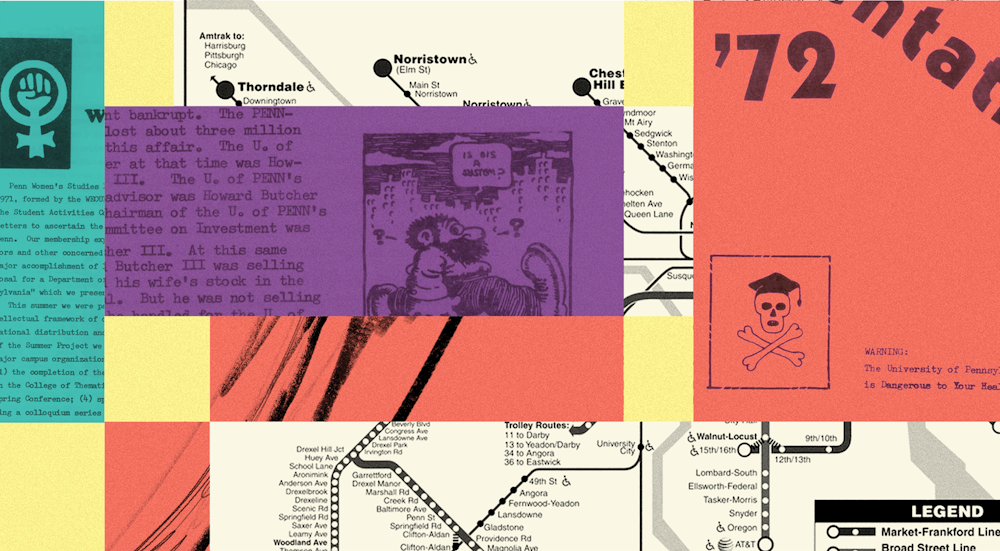

“WARNING: The University Of Pennsylvania is Dangerous To Your Health,” reads the typed subhead on the 1972 Disorientation Guide, the first edition of the now regularly produced student activist response to Penn’s traditional, institutional orientation.

The ‘72 DG is a bright pink, 52–page pamphlet that was sent to me by Owen*, one of the writers and editors of the upcoming 2024 edition. Today, the pamphlet lives primarily on the DG’s Instagram and their website, but its heart remains the same—to be a platform for student activists who want to effect change in the University.

The Disorientation Guide started with the ‘72 pamphlet and has been an on–again and off–again production orchestrated by student organizers on campus since. Penn having one isn’t unique, but it’s notable. With a 54–year legacy, the DG is an archive of the social issues of the time, all from the perspective of Penn students and how such issues are felt at Penn. In recent years, editions have focused on issues like the UC Townhomes, or racism and sexism at Penn. This year’s issue, according to writers and editors interviewed by Street, will have an additional focus on pro–Palestinian activism on campus and Penn’s temporary open expression guidelines.

The Disorientation Guide’s aim is to provide a non-institutional perspective on Penn, from its politics to its history to its general goings–on, while also giving student activist groups a place to speak their piece. The DG covers both the hyper–local campus culture to much broader involvement Penn has had with Philadelphian and Pennsylvanian politics, like the MOVE bombing. But from each publication in the last three years from the revival, one thing has remained the same: the DG ends with a list of on–campus and off–campus organizations and resources that students can look to if they want to get involved with activism at Penn or in the broader Philly community.

These days, the pamphlet is accompanied by Disorientation Week, which is “an on–the–ground manifestation of the Disorientation Guide’s principle,” according to Owen. The title is a riff on New Student Orientation week. It’s a week of illuminating the activist groups and spaces at Penn, allowing them all to talk and host various events to get newcomers interested.

In 1972, one of the most pressing issues tackled by the DG was the Vietnam War, but the DG also discussed rape culture on campus, sexism in hiring practices, and being Black at Penn. “The anti-war movement was huge,” says Sherrie Cohen (C ’75). “The civil rights [movement] and then the Black Power movement was huge [...] and then the beginning of the Women’s Liberation Movement. That was just so exciting.”

Cohen, David Fair (C ’75), and Carol Tracy (a 1975 graduate of the College of General Studies, which is now the College of Liberal and Professional Studies), are buoyant in their Zoom reunion, talking animatedly about sit-ins in College Hall and fighting with the administration for a staffed Women’s Center as opposed to having “a little room someplace where we could have volunteers,” which Cohen says was what the University initially suggested as the Women’s Center.

“We were on the ground floor of that,” Cohen remarks. “[...] And many of the issues have stayed the same over the decades.” Indeed, many of the issues talked about in the ‘72 DG are still being written about today. One example is affordable housing, which the DG dedicated space to in their 2023-24 issue and The Daily Pennsylvanian has reported on frequently. Ken Kilimnik (C ‘73) notes that this issue is one that the DG is still focusing on and one he worked heavily on while at Penn, including contributing to the housing section of the ‘72 DG.

Both the ‘72 DG and the ‘24 DG also tackle war and conflict. The ‘24 DG will, according to its contributors, have a lot to say about student activism regarding the ongoing war in Gaza; the ‘72 DG placed the Vietnam War front and center. “I like to believe that the [support for] anti-war resistance was more commonly held within the university community,” says Fair, in discussing protests against the Vietnam War. “When I look at things that are going on now, like the recent Palestinian demonstrations, it brings back those memories.”

Kilimnik, on the other hand, says he’s not sure if the situation is exactly the same—the ‘72 anti–Vietnam War protests had to do specifically with the U.S. Army’s direct involvement with the war, whereas many of the demands of the recent occupation of College Green had to do with Penn’s and the United States' financial relationship with the Israeli government.

Cohen says she’s “thrilled that the pro-Palestinian movement is stronger than ever.” Tracy lauds the early efforts of the encampment: “I was seeing posts from people who were talking about these really important conversations that were going on between Jews and Palestinians, really serious, thoughtful [conversations],” she says.

And whose voices are contributing to those conversations is a question some are raising, with an increased focus on anonymity among student activists. Gone are the days when the DG’s contributors wrote their names on the inside cover of the booklet. Kilimnik argues that there’s a need for transparency in activism; anonymity avoids letting readers know whose voices are being amplified.

The ‘24 contributors, however, see this as a matter of personal safety and academic security. Owen, who, like all the other ‘24 DG contributors interviewed, requested anonymity to avoid University retaliation, is slow and careful when Street interviews him. “I think we are expecting some—at least a little trouble. Even if it doesn’t come, we are expecting and planning for it […] We use encrypted messaging services and non–Penn emails, because [the Penn emails] are monitored, and there is a possibility of [retaliation from the Center for Community Standards and Accountability] from this.” According to Penn’s Policy on Privacy in the Electronic Environment, “[w]hile the University does not generally monitor or access the contents of a student’s e-mail or computer accounts, it reserves the right to do so.”

Tracy notes that there’s also a financial element to the fear of University retaliation. She says that these days, students are graduating with a lot more debt and paying a lot more for tuition. “It makes people a lot more careful about the thought of getting thrown out of school and having a record around it. I think the price is much higher [these days] for that kind of activism.”

The potential negative response from Penn is certainly on the minds of some of the DG contributors. But a recent shift in the guerilla production and distribution of the guide—from physical to digital— works as extra protection from administration, says Sam*, a rising junior who is a writer and the website designer for the 2024 DG.

They add: “Honestly, this year, I’m really unsure on how people are going to take the Disorientation Guide […] but I’m very confident that the people who will want to seek out the information [will], and join us.”

There is a sense of pride in the palpable impact the DG can have. Indeed, Kilimnik says that it’s undeniable that the work of student activists had some sort of direct impact—a 1969 housing sit–in, for example, got the University to come to the table and talk to student activists about mitigating Penn’s impact on the community. Tracy and Cohen are quick to hammer home the ways that activism on campus led to the Women’s Center and the establishment of the women's studies program in 1973. “I think dissent is always good,” Tracy says. “I think that it pushes the needle, pushes the envelope. We always need to have people who are out on the edge.”

That group of people seems to find the DG—or else it finds them. Rising sophomore writer and editor for the 2024 DG Tara* discusses her initial involvement with the DG: she was first introduced to the DG via a flyer handed to her during NSO. Tara and her friends read it later that day. “It sparked a conversation. We’re at Penn, and we’ve just had a really rich week of being shown all these opportunities that can help us get involved in our community. And now what are we going to do to get involved in this other side of campus that we haven’t heard this much about?”

From there, Tara joined the DG. She says she wants to “help showcase a fuller picture of the power at Penn,” and investigate “who’s really running Penn and what types of interests or morals or values they might uphold.”

This reflects what’s to come for the fall issue: “A flagship and thematic focus of this year’s Disorientation Guide is who owns Penn,” says Owen. “There’s a lot of donor influence, donor voices influencing the administration this year, and the different policies—that will be a specific article, exploring that relationship in terms of the Liz Magill resignation.”

The sentiment of investigating what interests are supported by the University is one that was felt in 1972 as well, with high–profile protests against involvement in Vietnam, and against ROTC at Penn, to which the ‘72 DG dedicates an article. “One thing I love that we did is just examining the power structure of the university,” Cohen says. “[What made things like] the displacement of the Black Bottom so possible [was] because Penn had placed itself in the top of the city’s power structure.”

Owen agrees that the DG does a lot of work shining a light on power dynamics in and around Penn. But the organizers don’t want readers to stop there. “Now that you’re aware, this is how you learn to engage.”

The DG also is a living archive for generations in the future. “It’s important for, in my view, a historical record of, ‘this is what’s happening.’ These are our perspectives […] not just the Penn–sanctioned story.” ‘72 contributor David Spector, a student at Penn off and on from 1970–1975, agrees that the ‘72 DG does much the same, writing that “the booklet is a fair representation of us as individuals and as a group, the state of parts of the Left, and the critique of Penn as an institution—as things were at that time.”

Since this year’s DG will pay extra attention to pro–Palestinian activism on campus and the temporary Guidelines on Open Expression, Sam says that they want to shed a light on the suspensions of four students involved with the encampment on College Green this past semester. “The sanctions are just completely unjustified and unprecedented,” they say. “[...] We’re going to really dig deep into what’s happening and do a full report on Penn’s response and what actually happened at the encampment.”

Owen points out how the guidelines would impact who is able to share their opinions on campus. “If tabling on Locust is something you have to get approved by Penn, no matter what, or else you get kicked off, or you have a CSA case, there’s little to no chance that you could table about Palestine on Locust Walk.” He notes that pro–Palestinian organizations like Penn Students Against the Occupation of Palestine were delisted from Penn’s club directory in the spring.

But overall, the contributors to the Disorientation Guide have a lot of hope about what it can do for engagement with activism on campus. Tara, for example, expresses gratitude for the role it’s played in her early time at Penn, and how the DG connected her with “activist and cultural organizations on and off campus.”

Almost everyone who contributed to the Disorientation Guide past and present made it very clear that the DG is not — and should not be — above growth, criticism, and change. Kilimnik says that it’s important to be critical of everything and not believe everything you read, and that it’s important to understand other people’s point of view. He notes that he does not agree with a lot of what’s in the Guide today; he says that people’s opinions change as they grow, and people’s focus should be on creating a framework within which everyone should coexist, avoiding falling into an echo chamber.

Fair, an out, gay man, says that the gay rights movement is conspicuously absent from the ‘72 DG. “I never remember that community being seen as a constituency that we needed to advocate for until several years later.” Spector echoes that, noting that though overall the booklet did a good job of summarizing the activist atmosphere at Penn at the time, nowadays there would have been a more concerted focus on and integration of women’s rights and gay rights, and that they “probably would not have segregated the women’s or Black articles toward the back of the bus booklet!”

At the end of the day, the Disorientation Guide is a publication like any other—with an extra emphasis on public. “I think that anybody can digest it,” Sam says. “Anybody should be able to criticize it if they would like. We’re not perfect. As long as it’s constructive criticism, I don’t think that’s a bad thing.”

*Some names were changed to preserve anonymity.