Enchanting, eerie island–themed music plays over a stretch of ocean at golden hour as a luxury boat glides through the pristine water. A sheen of beauty, a bedrock of sin. Everything seems perfect, and nothing is as it seems.

Season 1 of The White Lotus brings us a gorgeous, riveting ensemble cast, a beautiful coastal resort in Hawaii, an iconic opening scene that balances humor against an unsettling undertone, a cinematic Pinterest board of clothing and jewelry with bonkers prices … and a pilot teaser with a corpse in a body bag that reminds us that at the end of this idyllic–ish week, someone is going to die. It’s some of the best television ever written.

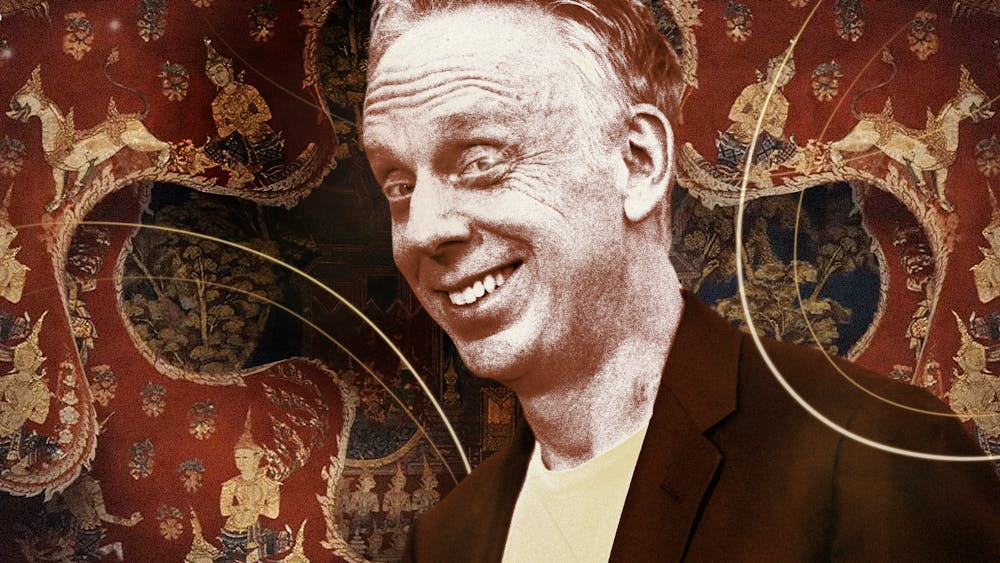

The White Lotus is a black comedy series written and directed by auteur filmmaker Mike White. It first premiered in 2021, and each of its three seasons—distinctly anthological from one another, with minimal character overlap—follows a group of guests and staffers at a different branch of the fictitious The White Lotus Resort & Spa. Over the course of one week, luxury and paradise devolve into messy family dynamics and a clever condemnation of the elite class. The show pivots from continent to continent with every new season (the location of White’s next directorial adventure is always susceptible to a plethora of internet theorizing and opining). Unlike his exorbitantly pampered fictional guests, White always makes sure to expand beyond the bubble of luxury and intentionally engage his narrative with the culture of the local area.

White bats a thousand with each script, holding up a funhouse mirror to the more taboo parts of society and forcing the upper–middle–class members of his audience into corners of tangible discomfort. It’s a classic and meticulously arranged “hate everyone” setup. Over the episodes we travel deeper into the world of The White Lotus, allowing the character arcs to flourish and rot, moving through firelit dinner scenes, hotel rooms, and pool–side lounges as White cross–cuts between interparty conversations. Characters are relatable one moment and abhorrent the next, entertaining all the while.

Right out of the gate, the show establishes that trying to define individual character morality in the name of locating a hero to root for can get complicated very quickly. Instead, the fun part of The White Lotus is watching them all make each other worse, and appreciating the detail–oriented cinematic mastery behind every dramatic plot point. As Tanner Stening of Northeastern Global News writes, “The series is shot through with interstitial symbolism. The effect is the feeling that there’s meaning to be found in almost every frame—that even the pattern in the wallpaper hints at some imminent disaster.”

The other major creative trademark of The White Lotus is the focus on meticulous and juxtaposed dialogue. In Season 1, scenes interlay a complicated interrogation of privilege. The show asks who is the “most” marginalized in a given situation … but how sorry can we actually feel for them, when the broader context is applied? Rachel (Alexandra Daddario) is arguably a victim in some capacity—the magic of her fantasy wedding is fading, and she now finds herself stranded in luxury with a petulant mama’s boy (who outright states that he only values her for her looks), wondering if she’s sold her soul to be a trophy wife. But the fact that she can now wipe her "tears away with a Louis Vuitton handkerchief,” as Natasha Rothwell puts it in a behind–the–finale interview, makes it hard to entirely sympathize with her and makes us understand why she ultimately retracts her annulment threat to instead just “be happy” with her husband Shane (Jake Lacy).

Another case study in privilege is Paula (Brittany O’Grady), a college friend of Olivia Mossbacher (Sydney Sweeney), who feels the effects of microaggressions as a middle–class Black woman in the midst of this well–meaning but slightly out–of–touch white family. (Steve Zahn and Connie Britton portray top 1% vague Gen X liberalism perfectly as the Mossbacher parents.) But when Paula tries to take herself out of her placement in the hierarchy by abetting a dangerous robbery—positing herself as the “good” guest that understands the plight of the poor and exploited—it backfires horrifically, alienating her both from the locals she tries to “save” and the Mossbacher family that, for all of their elitist faults, have very generously invited her to join their expensive vacation.

If Season 1 explores hypocrisy, privilege, and exploitation, Season 2 dives headfirst into questions about fidelity, patriarchy, and the dark side of sexual liberation, set against a Sicilian sky. White’s sequel season is not only an endlessly fascinating continuation of his attempts to scrutinize how wealth warps its glamorous victims, but it also bumps the level of action and sexual shock value up a notch from Season 1, which works well. While Season 1 doesn’t shy away from adult content—Paula’s clandestine fling with a hunky bellhop Kai (Kekoa Kekumano), for example, or Armond’s rowdy drug–induced night with his young employee Dillon (Lukas Gage)—it almost feels tame in comparison to Season 2.

The show’s first introduction to a potential gay incest storyline (well before that season three episode had viewers clutching their pearls) serves as a well–timed episode five cliffhanger. Local sex workers Mia (Beatrice Grannò) and Lucia (Simona Tabasco) have relations with various wealthy hotel patrons, including, separately, a sex–addict father (Michael Imperioli) and his bookish son (Adam DiMarco); White’s invocation of the exploitation of the underserved by the powerful takes on a new, more graphic form within the Italian setting. Two couples build up an insidious swinger vibe over the course of their joint vacation: the characters of Aubrey Plaza and Will Sharpe wear their insecurities on their sleeves while the other couple (Meghann Fahy and Theo James) conceal theirs behind a sparkling facade. The tee'd up mystery of whether or not anything unforgivably unfaithful happens is more indicative of the characters’ journeys than actually showing the raunchy scandal of the cheating ... another classic White subtlety.

This brings us to Season 3 and a new brand of exploitation: the commercialization of spirituality and identity–seeking into the highly–anticipated setting of Thailand. The premiere episode garnered 2.4 million views, marking a 57% increase from its Season 2 counterpart and proving that the fanbase of The White Lotus has rapidly grown more into the mainstream since its early pandemic–induced cult following days. It is also one of the closest things we have to a modern–day water–cooler show, a brand that HBO in particular has been attempting to craft for itself through its weekly released dramas.

Millions tune in each week for the next installment, but in the past decade or so, communication around television has expanded beyond simply texting your friends your live reactions or talking spoilers in the break room at work. Platforms like Instagram, Tiktok, and Twitter allow niche memes and fan theories to run rampant across the internet at a scale that feels particularly unique to this decade. Gleefully reshared clips of Parker Posey’s iconic North Carolina accent, videos that freeze–frame on easter eggs to build the framework for an intricate prediction of who will die in the finale, and thousands of comments discussing anything relevant to the show.

Season 3 blends pieces that worked well in the past seasons into the present one, inserting the highest peaks of drama and graphic sex into a familiar foundation of interlocked storylines that carefully become unwoven through familiar dialogue–heavy scenes. The catty, surprisingly realistic conversations between the three older women (Carrie Coon, Leslie Bibb, and Michelle Monaghan) tell us just as much about the season’s themes as patriarch Timothy Ratliff’s (Jason Isaacs) jarringly–edited psychological descent into suicidal ideation. The brother–on–brother incest—yes, we’re going to talk about it—carries far less of a narrative sting without the building parallel of the brothers' strange characterizations. Even that Sam Rockwell monologue, already lauded as Emmy–deserving, gets to the essence of White’s creative M.O.: Underneath all of its autogynephilic shock value, it’s incredibly written.

And yet, an interesting theme across the negative responses is one of unsatisfied boredom, more so than I have seen for its predecessors: Fans complain that the episodes drag at a snail's pace, that this is the worst season, and that the ending is unsatisfying.

Everyone is obviously entitled to their own opinions, and I would never blindly defend every facet of a creator’s work, even one I admire as much as White. What I am more interested in is the way that the creative agency of fans on the internet is more prominent than ever before and the way they, consciously or unconsciously, try to encroach on the boundaries of authorship. It may be the case that some fans want to abandon their media literacy, watch a few taboo orgies and drugged–up parties, and point their fingers at the freaky rich people doing weird shit, skipping straight to the murder and incest without doing the extra work to parse through the meticulously scripted character building and dialogue. But White’s confidence in his approach to storytelling is not so easily shaken.

His response to complaints is charged with the same witty snark that persists in his writing: “There was complaining about how there’s no plot. That part I find weird. It never did … part of me is just like bro, this is the vibe. I’m world–building. If you don’t want to go to bed with me, then get out of my bed. I’m edging you! Enjoy the edging.”

That’s not to say that there are no valid criticisms of the show, or that White’s ongoing project is a flawless evisceration of the rich. There is an element of real–life commodification that lingers both on and off–screen, slightly muddling White’s attempts to keep his social satire out of the trap of capitalist entertainment. Despite his cautionary themes, White also happens to be selling a lifestyle, and his vendors are the gorgeous cast with elegant old–money summer aesthetics. And it’s working: I would be remiss not to mention the slightly embarrassing fact that after watching Season 2, I happened across a targeted ad for the shirt that Leo Woodall’s character wears in Season 2 and tacked it onto the end of my Christmas list. Permanently implementing the White Lotus lifestyle is unattainable for a reason!

Whether White genuinely glamorizes his characters or more so demonstrates the inevitable reality of any showrunner's limits, White maintains control of what he can, and even the attractiveness of his actors can be construed as intentional beyond a traditional marketing perspective. Conventionally beautiful stars don’t seem out of place in this luxury setting, in the same way they might in a workplace sitcom or a college drama. Unlike traditional “real–world” media settings where supermodel attractiveness would turn heads, their power and privilege would not operate the same without their hotness.

It’s also apparent that White is more interested in taking things one step further—as usual—to toe that line of freakiness and uncomfortable realism than in simply creating paragons of sex appeal, and the range of his auteurship stretches into unexpected creative corners of the show. While there are plenty of “normal,” soft–pornographic sex scenes across the seasons, he also tends to use nudity, particularly male nudity, in unique ways. Every season premiere incorporates male full–frontal, and that’s not an accident, nor just a self–indulgent trigger for audience engagement bait. Modern masculinity and the crisis of re–masculinization are overarching themes stressed across all three seasons. White’s “subversive queer sensibility permeates the show,” as Men’s Health writer Philip Ellis suggests, and the nudity, like other provocative, queer–infused moments, is “never provocative for its own sake.” No matter how attractive an actor may be, the initial purpose of this nudity is never to make him a sex symbol.

To tear down your characters, you must first humanize them, so White attributes these blatant genital shots to different facets of the modern, almost–regular man. Steve Zahn’s testicular cancer scare demonstrates the sudden vulnerability of the untouchable generation. James’s exposed prosthetic is a calculated display of power over his best friend’s wife, establishing him early as a man who takes and does what he wants with little regard for the consequences. And when Saxon Ratliff (Patrick Schwarzenegger) exposes himself carelessly to his underage brother (Sam Nivola) as he leaves their shared bedroom to masturbate in the bathroom, it seems to be a little of both; a desire to claim dominion while trying to conceal his fear of losing control and appearing weak. The dark cross–section of these ideas lies in how the nudity presents itself, and that urge to push the limits of acceptable television and forge a new playbook for characterizations is what sets White apart from those before him. He very intentionally avoids making clear–cut statements about moral corruption and instead toys with audience desire, comfort, and perspective.

There are no real heroes and no real villains at the White Lotus. Even when the show dips its toes into high–drama moments and pockets of shocking action, the purpose is never to uplift someone and demonize someone else. It’s rare that a character is purely evil beyond audience recognition, or becomes a martyr; we grow to understand the roots of everyone’s motivations and psyche, until whether or not we actually like them as a character ceases to be the main point. Instead we take them apart in our heads, differentiating their unsettling, outrageous qualities from the ones that make us squirm and cringe and think about our own behavior. It’s not impossible for that line, at times, to blur.

Season 4 has long been greenlit and White’s audience knows the drill by now. Everyone will be a little too wealthy, a little unhappy, and a little fucked up. Someone’s going to die. Maybe multiple people. But if you stay along for the next stop on the ride, you have to accept White for the eccentric auteur he is. You have to appreciate that his devotion to character–building and nuanced, interwoven storylines and drawn–out scenes of masterfully–written conversation will always exist alongside the jaw–dropping spectacle and the incest and the infidelity and the tragic, bloody homicide. The slow unfolding of themes and character arcs is the show’s lifeblood, forcing audiences to sit with all of the convoluted moral ambiguity instead of gratifying them with easy answers and stimulating action.

So if The White Lotus is not for you, that’s okay. If it’s just the spectacle you’re after, you might be better off watching reality TV.