Thirteen cold–pressed juices a day, every hour, on the hour. Five coffee enemas. Everything green, everything clean. No need for chemotherapy, surgery, or long, terrified stays in hospital rooms. If you’re just diligent enough, your cancer will go away.

In 2013, an Australian influencer skyrocketed to fame after publicly claiming to have beaten her malignant brain cancer through healthy eating alone. Belle Gibson sold sick, desperate, and vulnerable people an enticing idea, leading them away from traditional medicine and towards the glittering mirage of alternative wellness. Her recipe app, The Whole Pantry, received hundreds of thousands of downloads in anticipation of her cookbook of the same name.

If only any of that were true.

Since then, it has been revealed that Gibson entirely faked her cancer diagnosis. There was never a malignant brain tumor, never a round of radiation, never even a hospital or an oncologist who diagnosed her. She endangered the lives of countless people by giving them false hope for a cure that never existed. Now, ten years later, her story has hit the screen.

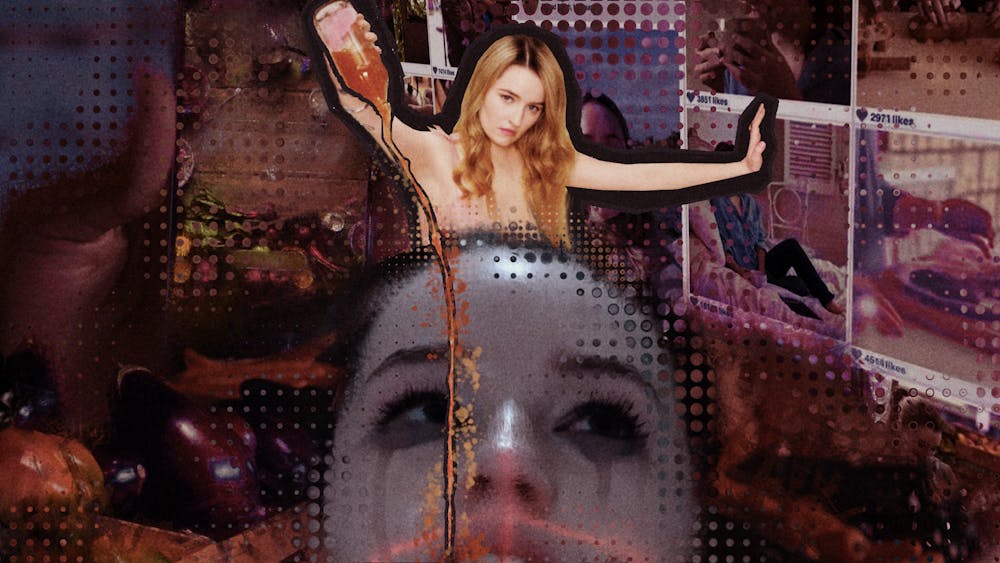

Each episode of Netflix’s Apple Cider Vinegar begins with the same few words: “This is a true story based on a lie.” Six hour–long episodes chronicle the rise and fall of Gibson’s wellness empire. Dated Instagram filters and a best of 2010s soundtrack remind us exactly when and where this took place, drawing focus to the culpability of social media and the digital age. Belle (Kaitlyn Dever) is intensely unlikable, which we see clearly behind the scenes, but to her followers, she appears authentic, warm, and inspirational, which allows her to carefully curate her narrative. “I love you,” she tells breast cancer survivor Lucy (Tilda Cobham–Hervey) in a café. But then she extends a hollow invite to her book launch and walks off. Lucy represents the thousands of people who fell for Belle’s scam—people who are only useful, in Belle’s eyes, to make her feel good about herself.

At the center of the series is Belle’s rivalry with fictional influencer Milla Blake (Alycia Debnam–Carey), who writes a blog also focused on healing cancer through alternative wellness. The difference? Milla actually has cancer: a sarcoma in her arm that nearly threatens amputation. Milla’s arc allows the series to shine a light on the flaws in conventional medicine. At a meeting with her doctors to discuss the amputation, they talk through and over her. Her request—“Please look at me when you’re talking about me. It’s my arm”—prompts condescension from the doctors, and her mother collapses into tears after one of them looks at Milla and coldly asks her, “Do you want to die?”

The scene is a chilling glimpse into the reality of the healthcare system as it exists today. With doctors like that, and the symptoms we see Lucy experience after she begins chemotherapy, it makes sense for Milla—and Lucy—to turn to experimental methods for help. Belle, on the other hand, has no such justification. Her entire endeavor is based on a need for attention—cancer just so happens to be the perfect sob story, waiting in the wings.

For all the deception at the heart of it, the show is remarkably dedicated to telling the truth. While most of the characters are fictionalized, many of the details of Belle’s time in the spotlight are taken directly from real events. The show itself tells us that, “Some names have been changed to protect the innocent,” which clearly, Belle is not. A good number of her lines are real quotes, including her initial proclamation of her cancer diagnosis: “He called me in and said, ‘You have malignant brain cancer, Belle. You’re dying. You have six weeks. Four months, tops,’” a statement immortalized in her now–shelved cookbook. One 2013 Facebook post from Belle claims, “I have been healing a severe and malignant brain cancer for the past few years with natural medicine, Gerson therapy and foods. It is working for me”—words which we watch Dever’s Belle type in the darkness of her bedroom. These constant reminders that what we’re watching is based in fact amplify the absurdity of the situation—and exacerbate our indignation at Belle’s actions.

Apple Cider Vinegar is one of many in a recent trend of dramatized retellings of true crime. Following in the footsteps of The Act and Inventing Anna, ACV falls somewhere in between the two, balancing misdeeds and deception with genuine concerns about sickness and health. While Belle weaves her web, Milla experiences genuine heartbreak over her illness, collapsing in her father’s arms in one heart–wrenching episode, which shows the aftermath of the treatment she believes in failing her. The two women are perfect foils of each other—juxtaposed in a way that makes us empathize with Milla and simultaneously recognize the extent and corruption of Belle’s lies.

But their truthfulness—or lack thereof—surrounding their respective illnesses is not the crux of their rivalry—in the end, it comes down to a fundamental difference in who they are. Belle chases an authenticity that Milla effortlessly embodies. Milla charms crowds of people who have to be paid to look twice at Belle. Milla is truly sick, but more than that, she is truly charming, authentic, and caring. She has something Belle doesn’t, and Belle can’t stand that.

At the end of the day, Belle equivocates so much—both in the show and in real interviews—that her true motivations are difficult to parse. She seems to be allergic to answering a question straight on. One thing remains evident, though. Regardless of whether she began her lie with malicious intent, she influenced who–knows–how–many people to reject treatments that might’ve saved them and place their faith in a fabricated cure because she didn’t know how else to connect with them. Belle’s crocodile tears flow freely, and for a few striking–yet–sparse moments, we do feel bad for her. At her core, she really is sick—just not in the way she has everyone believe. But these moments are sparse for a reason, and Apple Cider Vinegar is firm about that. Feeling lonely is one thing—endangering the lives of thousands of people by intentionally leading them astray is another.