It’s not hyperbole to say that David Lynch changed my life. There are those precious few artists whose work hits you at precisely the right moment in your life that forever alter its course. Through the perfect combination of circumstance and substance, they literally expand your field of view. They show you what art can be, and immediately your life is never the same. David Lynch did that for me and for so many others.

The first Lynch film I saw was Blue Velvet. I was 17, laying alone late at night in my bed, the light of my laptop flickering across my awestruck face. I had never seen anything like it before: something so drenched in evil, yet at the same time so earnest in its belief in the power of human connection.

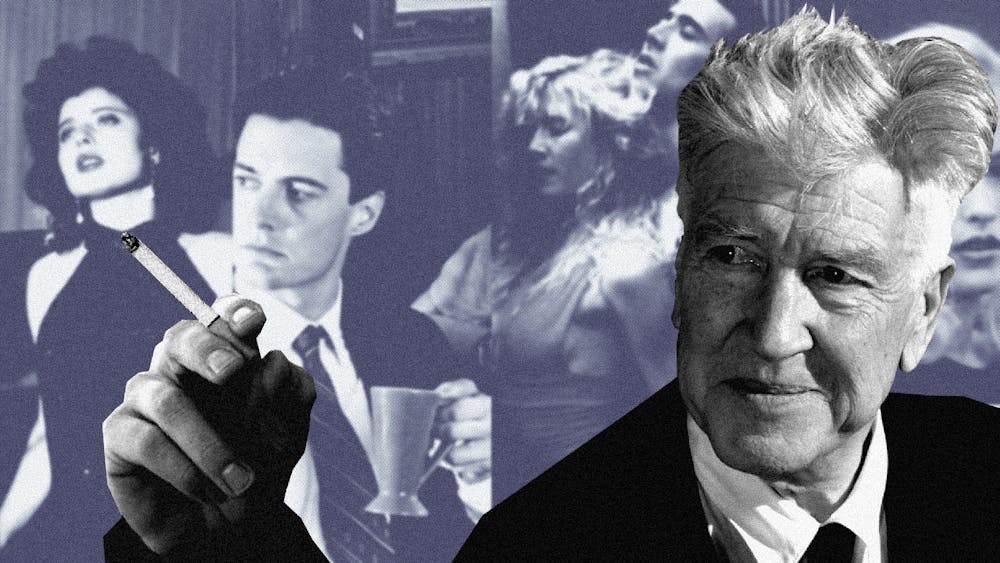

That duality between the light and the dark, the existence of pure good and universe–altering evil, that is what has defined Lynch. He saw this duality in the United States too: the white picket fences of Blue Velvet, the diner coffee of Twin Peaks, and the small–town bar in The Straight Story all juxtaposed with the violence—particularly against women—that lies just beneath this cheerful veneer. Lynch was the best at portraying both the best and worst of Americana on screen, usually at the same time. It felt like he understood this country, all that it can be and all that it really is, in a way no one else could.

But, despite all this artifice around him, the myth he himself helped create, what stands out above all is his supreme earnestness. It’s what so many Lynch imitators get wrong. They view his depiction of American mundanity as ironic, as if Lynch was somehow laughing at his characters for believing in it. In an era where irony and postmodernism has become the norm in mainstream film, Lynch’s earnestness feels like an oasis in the desert.

He loved his characters with all his heart, the good and the bad. It’s hard not to feel his overwhelming empathy for Laura Palmer whenever you watch any form of Twin Peaks, his genuine love for Diane Selwyn in Mulholland Drive, and the deep sadness he felt for John Merrick in The Elephant Man. Despite all the flourishes, all the dream logic that permeated his films, Lynch was ultimately a humanist above all else.

That’s not to say his work as a surrealist should be discounted, as it absolutely should not. To most of the general moviegoing audience of the past 50 years, Lynch represented the furthest extreme away from center they were willing to go. He was the “weird” auteur sanctioned, at least in some part, by the mainstream. This, I think, comes from the fact that his weirdness was so specifically and undeniably his own. Where others are weird just for the sake of being weird, or because of some need to be edgy and push boundaries, Lynch was weird because he was honest to himself. He did not care what was popular and what was niche, he loved what he loved and was unapologetic about it.

In this way, Lynch introduced so many to the idea of avant–garde art. So much of the landscape of modern film, modern music, and even modern art have been informed by generations interpreting and synthesizing Lynch’s aesthetic. If you read any piece of film or music criticism these days, there’s a good chance you’ll see said piece of art described as “Lynchian.” Like Franz Kafka and Thomas Pynchon before him, Lynch represented a style so his own that he changed the English language.

It’s impossible to talk about Lynch without talking about dreams. He was famously a major proponent of transcendental meditation, believing it allowed him as an artist to access the subconscious mind. Many of Lynch’s most famous works, from Mulholland Drive to Lost Highway to Inland Empire, touched in someway on the power of our dreams—and even those that did not still operated on some sort of dream logic. It felt at times like Lynch had the rare power the access the sublime, some unknown void beyond our world, and call back to us from its caverns and crevices—like he had the unique ability to explicate feelings we didn’t even know we had.

No one saw the world quite like Lynch. I think that’s ultimately why he impacted me so greatly. He showed me what was possible when an artist puts their point of view above all else. He did things I didn’t know a director—or any artist for that matter—could do.

So what happens when an artist like that leaves us? Fortunately, they leave behind a body of work we can bathe in and celebrate forever. In that way Lynch is immortal. His work that has inspired so many people lives on within them. And so, as I’ve tried to process this monumental loss, that’s where my mind has wandered: to all the wonderfully strange, wholly original little moments that Lynch gave us.

I think about the dinner scene in Eraserhead and what a perfect representation it is of the odd social norms we as humans have all agreed to follow.

I think about the overwhelming tenderness Lynch has for John Merrick in The Elephant Man, a level of empathy most filmmakers would overlook in favor of some crude joke or sight gag.

I think about the ending of his rendition of Dune when rain finally comes to Arrakis, something fully original to Lynch’s version of the story: a completely nonsensical change that makes for an astoundingly beautiful crescendo.

I think about the closet scene in Blue Velvet, one of the most chilling portrayals of human perversion I’ve seen.

I think about the scene in Twin Peaks when Garland Briggs states that his biggest fear is “the possibility that love is not enough,” the closest thing I’d argue Lynch had to a mantra.

I think about the “don’t turn away from love” quote in Wild at Heart, when Lynch finally gets to make his lifelong love of The Wizard of Oz literal in maybe his most earnest depiction of love.

I think about the scene in the woods in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me when Laura Palmer, on the verge of death, tells James her version of how she disappeared: the perfect encapsulation of the sadness Lynch could portray on screen.

I think about the mystery man scene in Lost Highway, a simple yet absolutely chilling entrance into the surreal.

I think about the final scene of The Straight Story, a mostly silent reunion between two brothers who have a lifetime of pain shared between them.

I think about the audition scene in Mulholland Drive, when Lynch shows us how performance, and what we hide within us, cannot be contained, and that we are all, to some degree, actors in our own lives.

I think about the rabbits sequence in Inland Empire, one of the most chilling and oppressive scenes I’ve seen in any major work; the scene is a look inside Lynch’s brain that reveals how singular he is as an artist.

I think about the moment in Twin Peaks: The Return when Big Ed and Norma finally act on their long–gestating love—which everyone, including Lynch himself, had been waiting for, for 30 years—as Otis Redding plays underneath.

I could list many more. And I know that if you asked a different Lynch fan their favorite moments, they would come up with a completely different list.

Last night, I watched Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me again as a way to honor Lynch. It’s one of my favorite movies of all time, and I’m always struck by the overwhelming sadness present in the entire runtime of the film, an entire town allowing Laura Palmer to self–destruct right in front of their eyes, her death inevitable. And yet, Lynch allows her a final moment of happiness, a respite from her short life of suffering and pain.

That, to me, is David Lynch: the ability to show us the deepest, darkest fears that lie within all of us, while still having the empathy to view us as people worthy of a final moment of joy and grace. He was the best of us. And I’m going to miss living in the world with him.