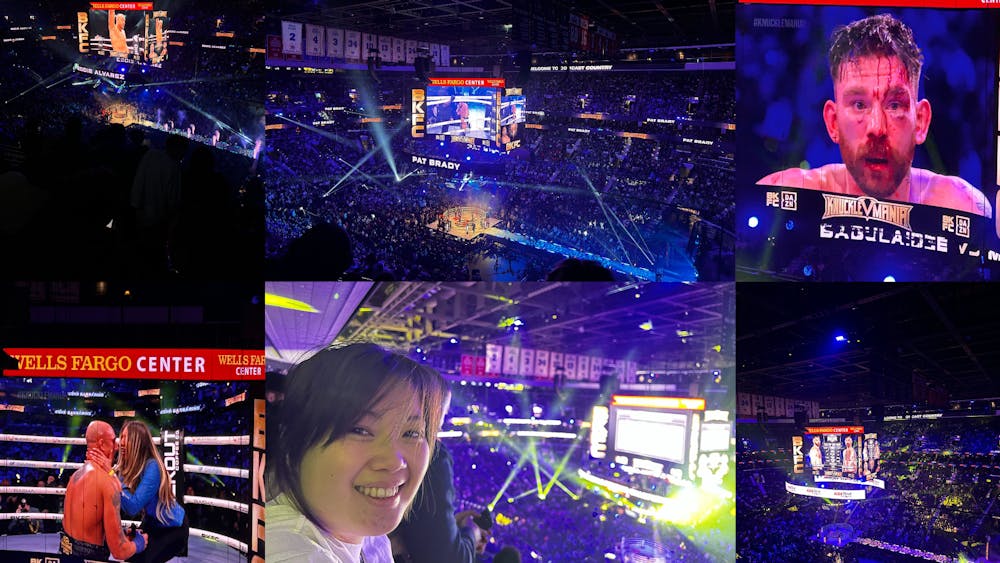

“Weeeeelcome to Philly, the best blue collar fighting city in the world,” the announcer’s voice echoes across Wells Fargo Center. We were just two of the 17,762 fans in attendance on Jan. 25 for Knucklemania V, Pennsylvania’s first ever state–sanctioned Bare Knuckle Fighting Championship.

The crowd’s attention was fixed on the square circle at the end of a catwalk—where 24 fighters would soon emerge and take their turns performing dances of violence in front of spectators thirsty for blood. One thing was clear: The age of gladiators clearly wasn’t left behind in Rome.

Headquartered in Philadelphia, BKFC was founded in 2018 by David Feldman—a native of Broomall, Pa. and a Temple University graduate.

“I started this vision back in 2009. I did a bare knuckle fight in a warehouse in South Philly—six people in attendance, one bare knuckle fight—and that was it. I knew we had to do this,” Feldman said at a pre–event press conference on Thursday, Jan. 23.

Unlike contemporary boxing, which requires the usage of boxing gloves in order to soften the impact of each hit, bare–knuckle fighting forbids the use of gauze or tape within one inch of the knuckles. Despite its strict set of rules—including no eye gouging or use of body parts outside of the fist—the sport remains extremely raw and bloody compared to other combat sports. In 2021, fighter Justin Thornton died weeks after being knocked out at his BKFC debut, sparking widescale condemnation from the fighting world, including from UFC founder Dana White.

Wyoming was the first state to sanction a BKFC fight, and on June 2, 2018, BKFC became the first promotion to hold an official knuckle fighting event in the United States since 1889. Despite being headquartered in Philadelphia, the Executive Director of the Department of State’s State Athletic Commission at the time denied Feldman’s request to officially sanction a BKFC event on nine separate occasions.

But after a change of leadership in late 2023, Feldman’s petition, now going to new SAC Executive Director Ed Kunkle, was finally successful. On Dec. 23, 2024, the SAC announced that Philadelphia would host BKFC Knucklemania V on Jan. 25, 2025 at the Wells Fargo Center. Pennsylvania is now the latest addition to a growing list of over 30 U.S. states that have officially sanctioned bare–knuckle fighting.

Bare–knuckle boxing was originally popularized in the British Isles, and it didn’t reach the United States until the late 19th century. The National Police Gazette—a men’s lifestyle magazine founded in 1845 that focused on crime and sports—became the first organized boxing sanctioning body in the country and started issuing championship titles in 1882. The sport lasted seven years before it began to fade—unable to compete with gloved boxing events that were more widely accepted in the mainstream.

Outside of the ring, people have been bare–knuckle fighting throughout history. As a result, the sport has branded itself as a working class pastime. There are no added costs of equipment or training gym fees when it comes to entering bare–knuckle boxing—all you need is your fists and a willing opponent.

For the four Philadelphia natives fighting that Saturday night, bare–knuckle boxing was an opportunity to transform fighting from an act of pure violence into a way of life. All hailed from a working class background. One fighter, Zed ‘King’ Montanez, credited the sport with saving him from going down “the wrong path”.

The Philadelphia favorite was probably native John ‘Johnny Garb’ Garbarino. Garbarino was kicked out of 12 schools for fighting and arrested twice before turning 18. Garbarino turned his life around after learning how to cook at the Gloucester County Institute of Technology while also becoming a student of martial arts. Years of fighting had sent him down a troubled path, yet those very same instincts became a means of survival in the ring.

In his BKFC debut, Garbarino walked out wearing a gladiator kilt to the tune of "Eye of the Tiger." As an Italian American from Philly who has worked with unions in the area, Garbarino seemed a modern–day Rocky, even being introduced to the crowd as the "Italian Stallion."

Garbarino was a crowd–pleaser, knocking out his opponent in the dying seconds of the first round before getting down on one knee to propose to his girlfriend. The cheering was loud, but it couldn’t compare to the applause he received following his first words when he was given the microphone. “I want to give my lord and savior Jesus Christ a shoutout,” Garbarino proclaimed as he made the sign of the cross.

The star of the night, however, was the decorated and beloved Philadelphia fighter Eddie ‘The Underground King’ Alvarez. Like the other fighters of the night, Alvarez saw his talents with his fists as his way to a better life. And while he wrestled in high school, Alvarez considers his greatest skills those he developed while defending himself on “the streets."

Alvarez, already a star in the UFC world, was advertised as the title fight of the night. Over 17,000 fans were in attendance, smashing a previous indoor Philly boxing event attendance record set in 1976. Much of the crowd were first–timers to a bare–knuckle fighting event, but they brought the same energy that they would for any other major Philadelphia sporting event. While there were some spectators wearing BKFC merchandise, most of the crowd showed up wearing a shade of green more commonly spotted at the arena’s neighboring football stadium. By the time the night was over, no less than 25 “E–A–G–L–E–S, Eagles!” chants had made the rounds.

In a sense, the entire event felt like one massive pregame for the Philadelphia Eagles’ NFC Championship game, set to kick–off the next afternoon at 3 p.m. As it turns out, some people would be attending both events. We overheard one man say to his friend, “Bro, we got to be back here in like 12 hours." Even the event–specific merchandise leaned into the well–known fanaticism of Philadelphians for their hometown teams, selling green shirts with the phrase “Philadelphia vs. The World.” At one point, the announcer for the event Brian Soscia played into the crowd’s support for the Eagles, saying “Today we spill blood in this circle, tomorrow we do it on the field.”

Leading up to the event, BKFC live-streamed a press conference on its YouTube channel on Thursday, Jan. 23. In the comments section, one user stated that “Every eagle fan that couldn’t afford a ticket to the NFL game will be there.” At the time of the press conference, the cheapest ticket to attend the Eagles game was $623—it only cost $40 to witness Knucklemania V.

But while the night may have started out as an NFC pregame, as the event progressed, the Eagles chants subsided and the Philadelphia faithful seemed to buy into the event itself.

After all, the ethos of fighting seems to permeate every corner of Philadelphia. Consider the Philadelphia Museum of Art, forever preserved in cinematic history as the home of the quintessential “Rocky Steps,” where the hero of the 1976 boxing film Rocky raced up and down. Rocky came to represent Philadelphia’s underdog spirit, the very city acting as his gym.

Off screen, the Broad Street Bullies of the Philadelphia Flyers were absolutely dominating the National Hockey League during that same period. The team from the 1970s made what was already a violent sport even more so, integrating fights into their game strategy to intimidate opponents. In fact, three members of the Broad Street Bullies—Dave Schultz, Joe Watson, and Jimmy Watson—were in attendance at Wells Fargo Center for the inaugural BKFC. Each was honored with a championship belt with the organizers of the event, attempting to connect the phenomena of bare–knuckle boxing to a much larger legacy of fighting.

“From the Bernard Hopkins of the world to the Broad Street Bullies, Philadelphia is, has been, and always will be a fighting city,” BKFC pre–event press conference host Cyrus Fees had said to introduce the event. “But now fighting in its most purest form is coming to Philly.”

By the first knock out, less than an hour into the four–hour fight, the crowd was enamored, sharks drawn to blood in the water. The EAGLES chants faded away, replaced with a different arsenal of cheers. All it took was for one person in our section to scream “Kill him” before phrases such as “Rip his head off” became staples for the rest of the fights. It felt as if we had gone back in time over 650 years to the Colosseum.

“The louder you get, the harder they hit,” was Soscia’s go–to phrase to in between fights. Soscia continuously reiterated the primal nature of the sport, feeding off the crowd’s desire for bloodshed. At one point, he stood at the center of the ring shouting “Watch the blood spill all for you, Philadelphia,” before pointing at one section of the audience, calling them animals while pounding his chest.

The crowd clearly indicated their values with their cheers. In the very first fight between middleweights Itso Babulaidze and Bryan ‘Iceman’ McDowell, the crowd booed as a timeout was called on behalf of McDowell after he sustained a particularly tough set of blows. But when McDowell signalled that he wanted to continue despite the blood streaming from his nose, the stadium reverberated with hoots and hollers.

Yet the audience was not unilateral with its respect. Their cheers seemed akin to an experiment in defining their ideal masculinity. For example, heavyweight fighter Zach ‘Shark Attack’ Calmus was received with hostility, scorned for his long hair. “He looks like a queer,” shouted a man with his hands cupped around his mouth.

Later in the night, when heavyweight fighter Steve ‘Panda’ Banks first made his way into the ring, the crowd showered him with jeers. Standing at 6 foot 5 and 289 pounds, Banks didn’t quite look like the ideal muscular fighter that the crowd was looking for. A man sitting behind us in the nosebleeds hissed: “You fat fuck! Get on a treadmill!” After knocking out his opponent to win, Banks seemed to have won a reluctant crowd’s approval. When the camera panned to Banks, he put up a sideways thumb and slowly turned it upward—a common practice at gladiator fights to indicate a fighter winning the support and approval of the crowd.

Even with the crowd’s bloodlust, strict boundaries were drawn between what was and wasn’t acceptable. In a contentious round between bantamweight fighters Noah ‘Cannon’ Norman and Phil ‘Hitman’ Caracappa, Norman had the crowd cheering him on as he had Caracappa on the ropes. The support quickly turned to disdain when Norman laid a late hit to the head on Caracappa after the referee separated the two, immediately disqualifying Norman from the competition.

The shouts of “You dirty fuck” and “Fight like a man” made one thing clear: Though the crowd was there to revel in violence, there was something “unmanly” about the act of cheating.

During that fight, it wasn’t just Norman tangling with Caracappa. Two fans sitting in the section right next to ours were locked into their own back–and–forth argument. It quickly devolved into a measure of masculinity, as one man spat at the other, “I got bitches on their knees n***a.” Later in the night, another fight erupted in our section—this one physical. Several rows cleared out to follow the action into the concourse.

Between the two of us, we had been at the Wells Fargo Center previously for a handful of 76ers and Flyers games in addition to concerts. Neither of us could recall encountering U.S. military recruiters at the arena. But when we entered the lobby ahead of KnuckleMania V, front–and–center were three U.S. Air Force and Space Academy recruiters.

It seemed like it was an effective strategy, too. There was a constant stream of men in line at the table, waiting to test their strength on a grip machine that the recruiters had brought with them. After talking with one of the recruiters, an Air Force Technical Sergeant, she told us, “We’ve had a lot of good prospects tonight.”

The recruiter mentioned that while they sometimes recruit at 76ers games, they are always active at events like the BKFC because “we sponsor them.” We were unable to find any sources online that corroborate this claim that the U.S. military directly sponsors events like the BKFC. Still,there was an undeniable ethos of patriotism that permeated the stadium. The announcer repeatedly labeled the fighters in the rings as “warriors,” reminiscent of the U.S. Army’s Soldier’s Creed: “I am a warrior.” In the few fights where an international fighter entered the ring, the crowd would immediately erupt into spontaneous chants of “U–S–A." One fighter, Apostle Spencer, entered the ring fully decked out in red, white, and blue--only to be knocked out a few minutes later.

The Star–Spangled Banner—traditionally performed at the start of a major sporting event—didn’t come until right before the last fight of the night. The choice was clearly made to ensure the crowd was amped up as much as possible before the main event, as the anthem’s conclusion was followed immediately by “Seven Nation Army” blasting from every speaker in the arena.

All evening, the arena had been full of energy and cheering. However, the atmosphere shifted uncomfortably as the first feature fight of the night began—the all–female face–off between Bec ‘Rowdy’ Rawlings and Taylor ‘Killa Bee’ Starling. As Rawlings and Starling began their fight, the noise levels suddenly dropped several magnitudes in terms of intensity—we could pick out individual instances of heckling which had been impossible with the previous fights. It was as if the crowd no longer knew whether or not it should be cheering.

These two women seemed to confuse the primarily male audience. These weren’t the first women to grace the ring in this testosterone riddled atmosphere. All night long, ring girls decked out in leather bikinis held up the match numbers—and encouraged by the announcer, the crowd wolf–whistled and ogled them. But these two women—both of whom were white and blonde, yet heavily tattooed and muscular—seemed to confuse the crowd's dichotomy of fighter and feminine.

As the two women threw haymakers at each other, the crowd oohed and ahhed. But there were no calls to “Fight like a man” as had popped up in the previous fights. After all, these two weren’t men. There were no calls to “Take her head off.” While there were some sexually charged comments such as “hug it out” and “make out,” the spectators mostly sat in uncomfortable silence—an uncomfortable silence forced by two women who were proving with each passing second that they could be just as violent and ruthless as their male counterparts. After all, if two women could very well beat up most of the spectators in the crowd, what did that mean for the hypermasculine culture of bare–knuckle fighting?

BKFC seems to have won over its audience that first night at Wells Fargo. The beginnings of BKFC, riddled with yellow tape and criticisms of violence, seem reminiscent of its far more popular counterpart UFC, despite the attempts by founder Dana White’s attempt to separate the two. Like UFC, BKFC seems to offer a novel violence to entertainment fighting. A number of UFC fighters have even left to join BKFC. After all, like BKFC, it wasn’t long ago that the UFC, deemed violent and dangerous, struggled to find venues and supporters, until one investor decided to bet on the combat sport—an investor now better known as the President of the United States.