Engaging with the rich history of Philadelphia’s Black communities requires balancing the specific and the universal—examining the unique, localized histories of individual neighborhoods and people while also identifying broader themes and shared experiences that connect them. These local histories form a diverse tapestry, challenging the idea of a single, monolithic Black experience in Philadelphia, while still revealing common struggles, triumphs, and cultural threads. Temple Contemporary’s exhibition Black Like That: Our Lives as Living Praxis furthers this dynamic exploration, contributing to a unique vision of art as living praxis—an art informed by both archival research and engagement with Philadelphia’s neighborhoods.

Three artists—Pat Phillips, Karyn Olivier, and Tiona Nekkia McClodden—worked for nearly two years producing paintings, sculptures, and videos, as well as organizing public interventions in various areas of Philadelphia. Their works delve into distinct yet interconnected themes: Phillips examines Black existence, ownership, and anti–Black violence; Olivier looks at unseen spaces that pose “blind spots” in our interpretation of historical and present–day perspectives; and McClodden explores the work of “re–memory” and Black queer figures who have been neglected. Together, their efforts invite audiences to participate in a dialogue about Black history and the role of art in communicating struggle.

Through this innovative exhibition, artists temporarily leave the walls of the gallery behind, moving out into communities to “activate” zones from which inspiration has been drawn and local histories remembered. In this way, both a gallery exploring Black existence through disparate but connected lenses of labor, housing, violence, queerness, and everyday life, and activations that directly enter communities take part in a living dialogue.

The Gallery

Housed in Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Black Like That inhabits clean, white walls and shiny floors. Each piece commands attention against the sterile backdrop, whether it’s Olivier’s Grief and Loss—an archival photograph embedded in drywall and metal studs, weighed down by sandbags—or Phillips’ Landlord Special/Open in Case of…, a painting addressing themes of Black ownership. While these works stand out individually, they also work in concert with one another. This consonancy, according to assistant curator William Toney, was one of the best parts of putting together the gallery. “[One of my favorite experiences] was to see … these beautiful works that really were about different geographic locations within the city, but how, as artworks, they really were in symphony together, in concert together,” Toney says.

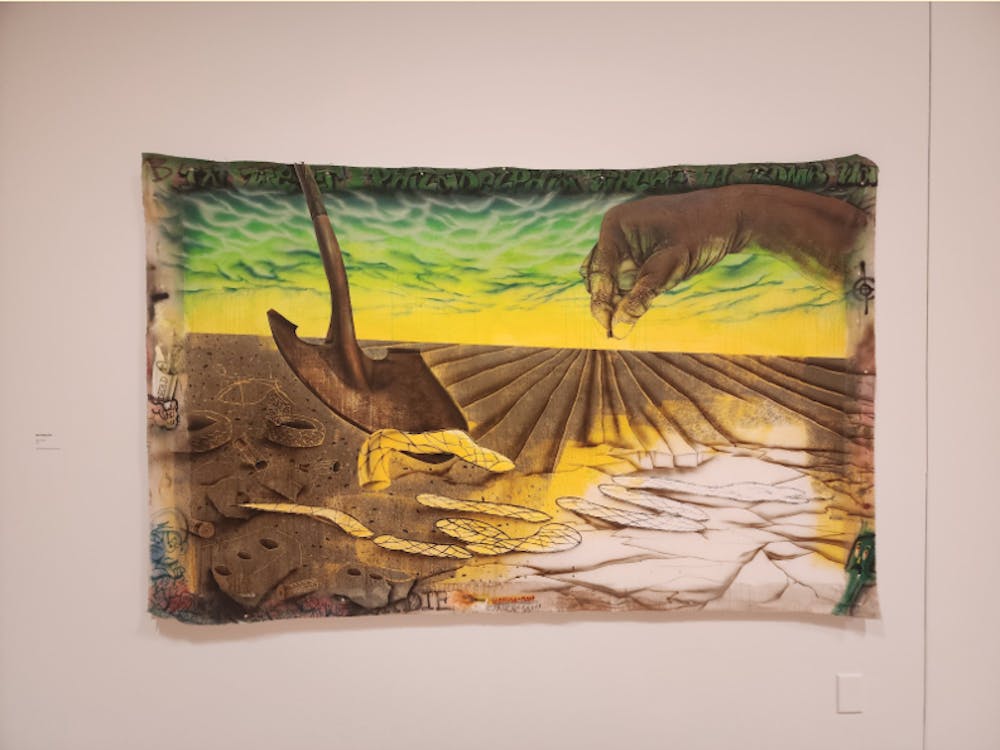

Photo of Landlord Special / Open In Case of….

Courtesy of Pat Philips.

Phillips’ large painting installments tower over the gallery, essentially forcing the audience into reflection about Philadelphia and their place in it. Drawing from the tradition of graffiti, Phillips not only uses formal elements like tags, phrases, and doodles, but also discusses themes of protest and overpolicing taken from the practical element of street art. Originally from Louisiana but living in Philadelphia for the duration of the exhibition, Phillips has found many resonances with his past interests and has discovered further inspiration through learning of momentous events in local Black history, like the MOVE bombing.

After entrenched frictions between police and the Black liberation group MOVE reached a head in 1985, the city dropped a satchel bomb on the group’s house, killing 11 people and destroying 61 homes in West Philadelphia. Deeply affecting the community, this atrocity still remains not only a watershed historical marker but also a present issue. As recent as this fall, further controversy over the mishandling of human remains by the Penn Museum has brought indignation from the community.

Phillips takes the sensitivity of his artistic subjects into account, using self–reflection to temper wild creativity. “I always look internally and think of my own skin in the game and the narrative, which is why thinking about MOVE and overpolicing and things like that are largely a part of my work, because that’s just where I started from. And then I just start digging into the history,” Phillips says.

The history of MOVE and the treatment of Black Philadelphians in the 1980s can be seen in Landlord Special. In this lively work, Phillips comments on the practice of slapdash maintenance landlords would do to cut costs when dealing with tenants. While some of this shoddy work pertains to poor painting and cosmetic jobs, there were much more hazardous practices such as keeping old pipes, HVAC systems, or using harmful construction materials. In Landlord Special, Phillips depicts a figure painting an apartment white with lead paint from the brand Rust–Oleum, which was only outlawed in 1978—the same year as a major standoff between MOVE and the police in Powelton Village.

The painting shows a toddler going for the phone of a Fisher–Price toy; they are not yet completely covered in the white paint but seemingly will be. The toy looks up as if it knows the health risks involved with the paint accosting it. In the floorboards underneath the painting and the Rust–Oleum cans propping it up, one can find an image from Tyler’s Charles L. Blockson Afro–American Collection of Black servicemen, on top of which lie bullets. This evokes the unfair treatment experienced by Black soldiers in terms of benefits denied to them after World War II. Tying together these different historical facts, Phillips is able to communicate not only themes surrounding health and biopolitics, but also Black ownership and its unequal history.

Scattered around the painting are phrases—one of which reads, “A mouse only falls for the trap because it doesn’t understand why the cheese is free.” Another painting, Join or Die, which deals with themes of labor and the building of the United States, has text scribbled in the margin which reads, “In West Philadelphia where a bomb won.” Phillips uses the margins to help shape the work. “The edges echo my background, going back to … graffiti. It’s a lot of doodles and crude drawings that sort of helped me get to the finished product. … Graffiti, while in itself is very political, it’s … the vessel that helped me come to some of the conclusions and inform a lot of the dialogue and language that I’m interested in,” says Phillips.

Photo of Join or Die.

Phillips is not the only artist in the gallery who utilizes the written word. Indeed, McClodden also does in the Sleight of Figure series, which deals with the Black lesbian musician and performer Gladys Bentley. On an all–black leather hide, with black leather dye and paint, the piece Headlines reads, “[Q]ueer and even sported a girlfriend/twilight zone of sex/I am a woman again/risque/nimble in manipulating the ivories.” McClodden also uses the motif of a top hat throughout the Sleight of Figure series, which expresses Bentley’s habit of cross–dressing.

McClodden at times delves into granular history, even including maps of Philadelphia. This attentiveness to geography and space runs throughout the exhibit, with the artists demonstrating a fidelity and sensitivity to the locations where lives unfolded. For Olivier, this means a use of archival material and images from her native Germantown, which can be seen in her piece Lighthouse (Rite Aid, 6201 Germantown Ave.). Olivier uses local images to problematize the power relations that harm people of color, including housing insecurity and building practices.

Photo of Lighthouse Rite Aid (6201, Germantown Ave.)

Beyond the Walls of the Gallery

Nestled quietly in Germantown, a potter’s field—a communal burial site with unmarked graves—stands as a call for reflection. In 2015, residents of Queen Lane and the surrounding area fought to protect this historically Black burial ground. As part of an activation event, Black Like That and Olivier seek to explore the intersection of past and future, examining how communities can honor their ancestors while continuing to use shared spaces for enjoyment. The community continues to grapple with this question as local parents lament the loss of recreational space due to the memorialization of the burial ground.

To uphold the exhibition’s commitment to praxis, the activations are designed to give back to the community. For Olivier, this took the form of an intervention at Queen Lane, while for Phillips, with his focus on West Philadelphia and graffiti influences, it involved live painting and music at the Pentridge Station pop–up.

Phillips chose this Black–owned space, as it represents a forum for the surrounding communities. Working with an advisory board that includes community members, Black Like That taps into rich local histories to reach locals. Phillips finds this side of the exhibition just as important as the gallery wall. “I wanted to do something that could counter [the white wall space] that would be a little bit more festive, a little bit more celebratory, that could be in contrast with some of the work and the subject matter. … I thought this would be a way to not only bring a different approach to what was being spoken about in the paintings, but also celebrate other Black creatives,” Phillips says.

The live–painting aspect of the West Philly Activation highlights the inspiration of graffiti for Phillips and its importance in Philadelphia. Artists spent the day listening to music and working on large canvases hoisted onto beams and on walls. In attendance was Darryl “Cornbread” McCray, widely held to be the first graffiti artist of the modern world. Having not only living legends but also community members in attendance made for a successful activation. Phillips was wary of being an outsider talking about the community without actually engaging in it, but he counteracted this through an informed involvement with Philadelphia’s rich tradition of graffiti.

Art as Dialogue

The local histories of West Philly, North Philly, and Germantown create a vivid patchwork of rich, specific details, while also conveying broader themes of Black existence. Each artist explores a sense of struggle in their own way—Phillips through the MOVE bombing and Black liberation, Olivier by examining “blind spots” and power structures, and McClodden through queerness and “biomythography.” Though their works address distinct sites and tensions, the dialogue between their perspectives ensures a thorough and multifaceted exploration, leaving no stone unturned.

Bringing to the fore archival research, Black Like That utilizes collective history in an uncommonly active way. “[The most important part about this project to me] is to understand archival practice comes from both existing archives, but then also comes from creating them and doing research and being very active, and respecting the lived experience,” Toney says.

This sentiment of bringing art down to earth is echoed by Phillips, who emphasizes that for art to truly be a dialogue, it needs to meet people where they are: “We have to sometimes acknowledge how intimidating these sort of institutions can be. … I didn’t start off as someone who wanted to be an artist. I didn’t go check out the museums in my town when I was a kid. It didn’t feel like my scene. So as artists, we’re talking about a community, we’re talking about this group, we’re talking about that group. Sure, we’re having a dialogue about them, but sometimes, you gotta be able to meet people halfway,” Phillips says.