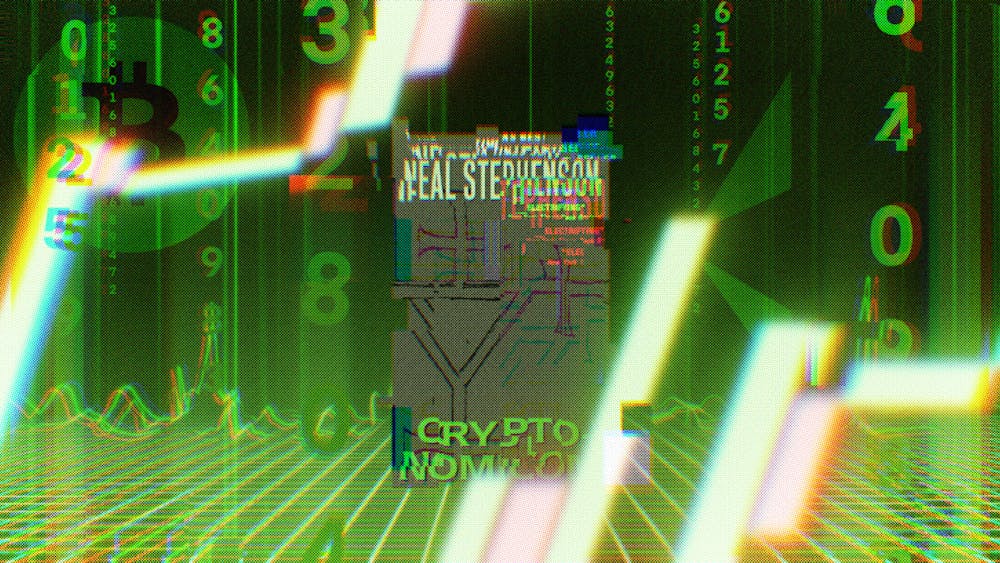

Today, Bitcoin hit 100,000. But long before crypto bros were salivating on Reddit, Neal Stephenson’s was imagining a blockchain future in his 1999 novel Cryptonomicon. Over the course of its 900–plus pages, the storyline spans half a century, ranges from the barren islands north of Great Britain to the jungles of Southeast Asia to the depths of the Atlantic Ocean, and features real–life historical characters such as Alan Turing alongside concepts which were ahead of mainstream society by the turn of the millennium.

Despite all of these complexities, the book is about a group of entrepreneurs in the late 1990s seeking to build a data storage facility—where people all over the world can place information free from government intervention—within the fictional Sultanate of Kinakuta. However, this data haven is largely a front for a much grander project: a digital currency which can be used by anyone around the world, untethered to a central bank.

The book includes technology which was around in the late 1990s. Beyond discussions of mathematical subjects like prime number theory and modular arithmetic, the characters use a software called Finux—similar to Linux—and are worried about being targeted with a specific type of hacking known as Van Eck phreaking, where hackers can read the information displayed on one’s computer screen.

But the biggest piece of technology in Cryptonomicon—the digital currency the characters attempt to create—didn’t exist in our world when Stephenson wrote the novel, but has become quite popular today, with the rise of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

In 1999, digital currency was just a theory. The first Bitcoins wouldn’t be distributed for another decade, and it would take longer for the cryptocurrency to achieve the prominence it has today. The idea of a currency untethered to any government’s central bank but which could be exchanged for goods just like dollars or euros would be was just a glimmer in the eyes of certain futurists when Stephenson wrote about it.

So, this part of Cryptonomicon’s story is quite prescient for its time. But Stephenson misses one key aspect of what makes Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies unique. They are, essentially, backed by nothing but the trust of the other people who use it. That is, Bitcoin only has value because other people think it has value. This fact has become a sticking point among critics of cryptocurrency and a vector from which they can assail its legitimacy.

The digital currency in the novel works slightly differently, however. This currency would be backed by a massive cache of gold, held in a mountain in the Philippines. Users could theoretically exchange a unit of digital currency for a certain amount of gold. Therefore, this currency has value because you can exchange it for gold, and everyone agrees that gold has value.

For all of Stephenson’s technical knowledge and the fact that he successfully predicted cryptocurrency, he got this one part wrong. This could have just been an error on his part. Even the most successful prognosticators of the future tend to get a few things wrong, especially when it comes to something as complex as cryptocurrency.

But there could be another reason for Stephenson to craft the story this way: It makes for better storytelling. A major part of Cryptonomicon is about these entrepreneurs trying to find the gold needed to back their currency. In the novel, it had been deposited in a secret vault by the Japanese army during World War II, and no one knew its location.

Having the novel revolve around the search for a mythical lost horde of gold makes for more compelling fiction than a group of people trying to set up the complicated mathematical functions which underpin the Bitcoin blockchain. Even with all of the talk of computers and mathematics, Stephenson is trying to tell a story, and his publisher needs to sell books. As a novelist, Stephenson’s job is to tell the most compelling story, and this quest for a long–lost stash of gold certainly benefits the narrative.

And this fact—beyond just the complexity of our world—is a key reason why art cannot always predict real life. Many of the stories behind how major parts of our world were created are not always interesting enough. People sometimes say that if a real–world phenomenon was a movie script, no one would buy it because it’d seem too unrealistic. Well, the opposite is sometimes true as well. If a novel accurately predicted a future trend, perhaps it would be too boring to even consider reading.