In the early glow of dawn, while the campus still lingers in shadow, Amaan Omer (C, W ‘25) steps into a quiet room, faces Mecca, and begins to pray. For Penn’s senior class president—a man bound to the weight of a double degree, double Chipotle bowls, endless meetings, and the pulse of campus life—this is one of the rare, sacred moments where he isn’t a leader or a student, but simply himself.

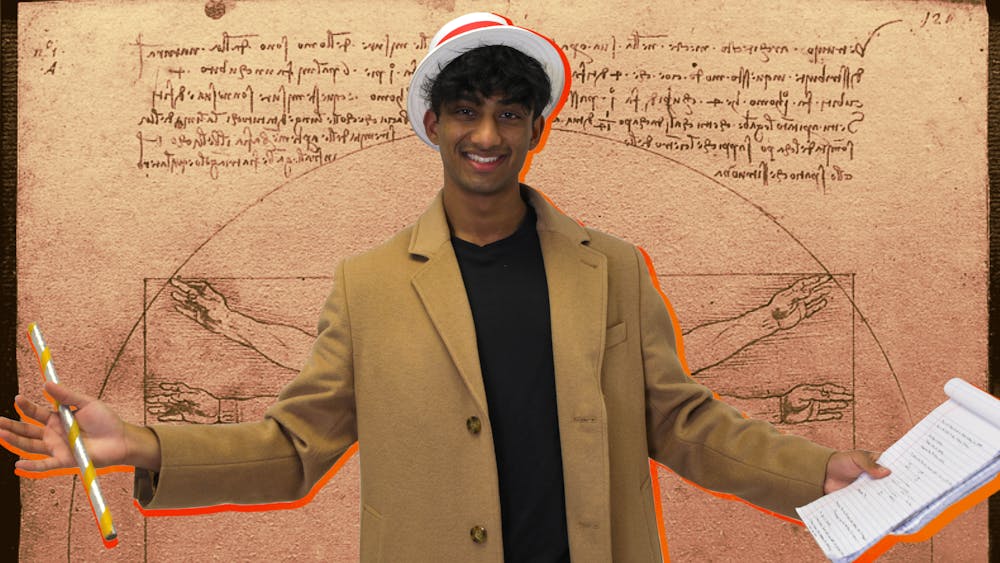

To an outsider, Amaan’s journey might seem like an unbroken chain of triumphs. He’s a Renaissance man with a resume as intricate as it is demanding, an Atlas capable of shouldering the entire world. But beneath these accomplishments lies a quieter story, shaped by fears he seldom shares with others; the unrelenting drive, the late nights when he questions if he’s enough, and the shadows of unfulfilled dreams that linger at the edge of his thoughts. For Amaan, ambition isn’t a road paved with certainty; it’s a journey through the fog, guided only by glimpses of purpose and a relentless desire to make good on the promises he’s made to himself.

His studies are driven by practicality and not prestige. He chose neuroscience and health care policy as a way to bridge two worlds—the science of the body and the strategy of systems that govern it.

His decision to take on both fields was shaped by something deeply personal: a memory of his mother, hurt by a medical oversight that could have been prevented. It was a mistake that would affect her for the rest of her life, leaving Amaan to wonder how many others had been let down by a lack of transparency. “It’s something I carry with me,” he says, his voice quiet but resolute. “I don’t want anyone else to lose faith in a system meant to protect them.” When an advisor in the Biology Department suggested he drop one degree instead of encouraging his pursuits, Amaan chose instead to switch his focus entirely, leaving biology for neuroscience, which he felt better supported his goals. The advice had stung, but it hadn’t stuck. Each semester since, he’s registered for seven, sometimes eight courses—a feat even by Penn’s standards—grappling with labs and policy seminars like a man juggling fire.

After his first year, Penn's Global Research and Internship Program gave him the chance to work on medical frontlines an ocean away. In The Gambia, Amaan came face–to–face with health care’s harshest realities. Gone were the theoretical frameworks and neatly bound textbooks; here, medicine was survival in its most raw form, stretched thin across lives that depended on more than the hospital could give. Paper records climbed to the ceiling, gathering dust, threatening to overwhelm a room already bursting at the seams. His goal was to implement an electronic record system, a project that seemed manageable back home but quickly became a lesson in adaptability. Computers were rare, storage space rarer, and the idea of “data management” seemed laughable at times. Yet, by the time he left, the digital records were in place—a fragile but crucial promise that the hospital’s history wouldn’t be lost in piles of paper. To this day, his system remains in use, a quiet testament to a project that had outgrown its original design.

But digitizing records was only one part of a daily struggle that felt like endless triage. The neonatal intensive care unit—a half–functional refuge against the staggering rates of infant mortality—was barely holding on, with the maternity ward beside it often flooding under the rainy season’s relentless downpours. Mothers arrived out of desperation, but the lack of privacy—overcrowded rooms, deliveries in full view—made many hesitate. The conditions were stark and unyielding, leading some to opt for the risks of home births rather than the indignities of public labor. For these women, the NICU and maternity ward offered not only critical medical care but small sanctuaries of dignity, rare pockets of protection in a place where safety and respect were often as scarce as the resources themselves.

One night, Amaan witnessed firsthand the life–or–death fragility of this system. A patient arrived with an open head wound, blood pooling on the cracked linoleum, and the doctors scrambled, only to discover there was no blood left for a transfusion. A quiet fell over the room—the kind of silence that answers questions before they’re asked. Amaan watched, helpless, as the patient slipped away, another life lost to a shortage that should never have existed. “I felt the failure as if it were my own,” he recalls. It was there, in that hospital room, that he realized his work wasn’t just a plan to manage health care; it was a duty to bridge a gap no one should have to fall through.

“When I left, I understood healthcare was more than policy,” he says, weighing each word. “It’s about responsibility.” The lesson traveled with him back across the Atlantic, a quiet realization that aspirations, at its core, must be tempered with empathy and guided by a purpose deeper than titles.

When Amaan first stepped onto campus, he wanted to find a community, but felt the quiet pressure to prove himself in every new role he took on. It was dance, unexpected and unfamiliar, that first offered him an escape. During his first year, he stumbled into Penn Raas, a South Asian dance team, and what began as a reluctant commitment to cultural roots quickly became his sanctuary.

In those early months, Raas became more than just practice sessions and performances—it became a second family. In rehearsals, he was surrounded by teammates who were more like older sisters, pulling him through the growing pains of his first year. Dance made him confront his stage fear, his doubts, his discomfort. But as he moved with his teammates, his mental fears gave way to physical freedom. The rush of stepping onto stage, heart pounding, became a ritual—a release, a reminder that he didn’t have to face his anxieties alone.

Raas was only the beginning. When he joined Broad Street Baadshahz as a sophomore, Amaan’s life took on a new intensity. If Raas was about warmth, BSB was all passion—a team bound by sweat and discipline, by late nights spent pushing their limits until the lines between exhaustion and exhilaration blurred. BSB was a brotherhood that demanded everything, a place where Amaan learned what it meant to hold himself accountable to something larger. Here, he found camaraderie in the rawness of competition, in the back–to–back hours of practice, in the relentless drive to perform not just as individuals, but as one body, one force.

That lesson hit home during their first national competition, where they placed sixth. Amaan remembers the silence that fell over them, the shock that had everyone standing there, unsure of what to say. “I’d never seen so many guys cry on stage,” he recalls. They hadn’t come this far to lose, but that night, they tasted the bitter edge of defeat. With the loss weighing on them, he rallied his teammates, channeling their frustration into determination. “Remember this feeling,” he told them, “and make sure we never feel it again.” They took his words to heart, returning to practice with a fresh resolve, the sting of that loss turning into fuel. Less than two weeks later, at another competition, they took first place—a victory that was sweeter for the pain they had endured. Now, they were the team to beat, and they carried that title with pride.

Mock Trial at Penn was where Amaan sharpened the skills he’ll carry into his future legal career. Each case was an opportunity to master the craft of argumentation, to learn how to think on his feet, and to distill complex issues into compelling stories. It taught him to be decisive under pressure—a battlefield where every pivot and question was significant. For Amaan, the experience was a rehearsal for the kind of advocacy he plans to bring to health care law and medical malpractice cases, where the stakes are even higher and lives hang in the balance.

Amid this demanding schedule, faith provided Amaan with clarity and purpose. The Muslim Students Association became his refuge, a space where he could step away from the pressures of leadership and connect with a community that shared his values. During Ramadan, he helped coordinate meals for fasting students, ensuring that hundreds of his peers had a place to break their fast together—a logistical feat that required as much planning as any of his other commitments. Even as class president, where neutrality is often the default, Amaan didn’t shy away from standing up for what mattered to him. “Faith guides me, not just in what I believe but in how I act,” he explains. Whether it’s ensuring inclusivity during Ramadan or speaking out on behalf of underrepresented groups, Amaan views his advocacy as an extension of his values—an essential part of the leader, and the lawyer, he aspires to be.

Faith is Amaan’s foundation, but it’s the drive to fulfill his potential that propels him forward, unwavering and unyielding. “I think about it sometimes,” he admits, “all the things I might leave undone—the paths I might never explore, the skills I may never truly master.” Every role he steps into, every late night and early morning, is part of a promise he’s made to himself: that no opportunity will be left on the table, no ambition unexplored. It’s not about chasing endless achievements; it’s about ensuring that his time at Penn, and beyond, is used to its fullest.

But Amaan’s ambitions extend beyond his own aspirations; they’re tightly interwoven with his family’s dreams. Chief among them is his commitment to retiring his parents early—this isn’t just about climbing a ladder; it’s a promise to honor those who have sacrificed for him, to offer them security as they once did for him. Every responsibility he assumes carries the quiet weight of this promise, adding a layer of purpose to each decision, each step forward.

For Amaan, the journey is one of love, not just for what he might become, but for those he’s doing it for. He is an Atlas by choice, a Renaissance man in action, relentless in his pursuit to do his commitments justice. In every role he assumes, there’s a strength that reflects the beauty of becoming, each challenge he meets a testament to dreams he refuses to let die.