As I took my seat on Friday night at the Academy of Music’s cozy Perelman Theater to hear chamber orchestra Sphinx Virtuosi, I reflected on other concerts I’d attended in this very same venue. Generally reserved for chamber ensemble performances (consorts, quartets, the occasional Baroque soloist), the Perelman is intimate, seating 650 as opposed to the 2,500 that its sister concert hall, Marian Anderson Hall, can manage. I’ve most often received an overwhelming impression of comfort from Perelman concerts: safe musical choices, small ensembles with a homespun feel, cute but at times banal performances … from regional youth orchestras to masterful but familiar solo pieces performed by Yo–Yo Ma, I’ve left the Perelman smiling in appreciation but never in astonishment.

All that was about to change.

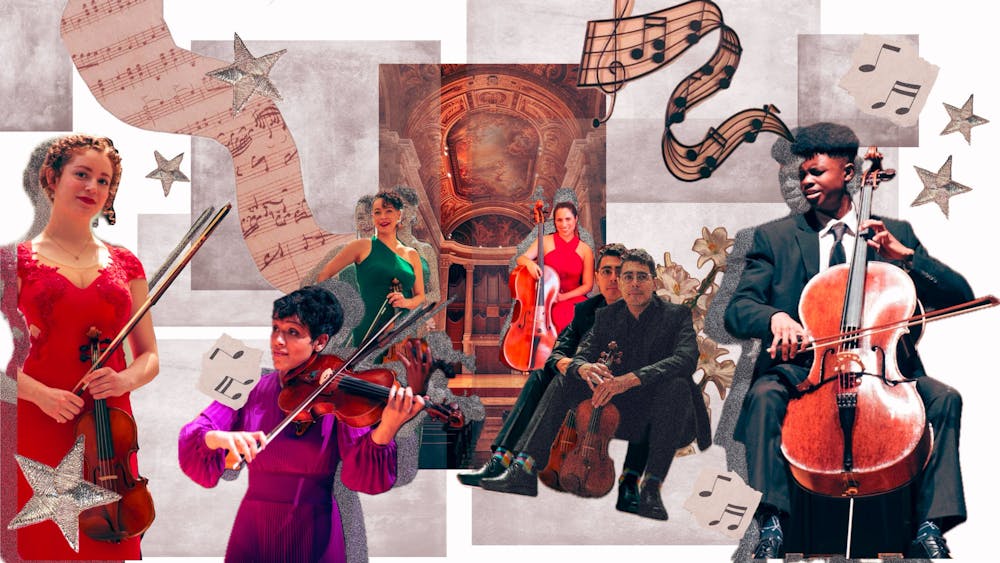

Sphinx Virtuosi distinguished itself from other groups from the moment they set foot on stage. Adorned with sequins, feathers, and bright colors, each member wore a different dress or suit, an uncommon occurrence at classical performances. It was a refreshing departure from the uniform all–black, which, while non–distracting, can at times feel a bit understated or even oppressive. But there was nothing oppressive about Sphinx’s stage presence, which somehow managed to pay homage to each member’s unique contribution while also maintaining the focus on the group as a whole. For example: Sphinx’s genius choice to remain standing throughout the concert provided the audience with a clear view of the ways in which the players moved with their instruments, moved with their musical lines, and moved together. And the program itself! Brimming with personality, each piece represented an individual musical moment that held its own against the others’ starkly different sonic textures and aesthetics. To cite the name of Derrick Skye’s ambitious and eclectic piece arranged for Sphinx, I felt as if I was beholding an “American Mirror,” a reflection of all the best things American diversity can offer: a dynamic montage of color, movement, and sound.

“Dynamic montage” is very on–brand for Sphinx Virtuosi, which describes its work as aimed at “evolving the breadth and impact of classical music.” A chamber orchestra derived from the Sphinx Organization (a nonprofit based in Detroit), Sphinx Virtuosi is composed of eighteen young Black and Latinx artists who represent some of the highest achieving performers in their field. This necessary orchestra offers a way forward from unyielding Eurocentric conceptions of classical music, proving that standards of excellence and musical openness can and should coexist. Everything, and I do mean EVERYTHING, about Sphinx Virtuosi’s performance on Friday pointed to this, the music perhaps most of all.

Some highlights of the evening’s program were the aforementioned American Mirror and Coleridge–Taylor’s “Four Noveletten, Op. 52.” The violin and viola harmonies in the Coleridge–Taylor were devastatingly (but wonderfully) dissonant, whilst the Appalachian melodic motif in the Skye made me lose my breath for its haunting beauty.

But the true show–stopper was Juantio Becenti’s Hané, a piece composed by 17–year–old Becenti for the 1998 Moab Music Festival. Becenti’s easy command of suspense had me on the edge of my seat, wondering which theme would dissolve into which harmony, or which scale would evolve into a sweeping melody. One moment in particular caused me to turn to my friend in the seat beside me, eyes wide, mouth agape. Following a passage of eighths layered atop a rhythmically identical dominant harmony, Becenti places a ritardando and splits the eighths between the cellos and second violins, resulting in a move from a rapid brook of sound to a graceful waterfall. For the successful execution of this moment alone, Benceti and Sphinx deserved the rapturous applause that followed Hané.

As I left the theater that evening, I couldn’t help but feel I’d witnessed a revolution. Mind buzzing, I waited for the arrival of my bus, knowing that Sphinx Virtuosi had achieved what they had set out to do: they had rattled me. My sense of musical truth sufficiently turned inside out, they had turned me out onto the streets of Philadelphia, to revel—in astonishment—at what had just been accomplished.