The young women file in one by one, a girlishly organized succession of hair–bumps, lace blouses and miniskirts; pale blue tights, kitten heels with bows and, of course, eyeliner. Thick, dark wings for watery marbles of gray or green and honey—a shock of young eyes in the black of the theater. Descending down the row, the young women exit off into seats, otherwise too far to see and lost in the blackout. Slowly but surely, the room is engulfed in a fog of girldom; a soft darkness abuzz with chatter, hushed giggles, and reverent utterances of "Coppola." Sofia Coppola.

Of course, there are others in the theater. Opening weekend has brought a full house: 20–somethings on dates, a married couple sneaking wine from a paper bag, older women in groups of three or more (evidently still deft with a curling iron). Hair is big tonight.

All have gathered this evening for Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla, the highly anticipated—and much needed, following Baz Luhrmann’s 2020 phantasmagoria of Elvis—rock ‘n roll revisionist Elvis story. Coppola’s film uniquely resists following the obvious star and instead plays according to Mrs. Presley’s 1985 memoir, Elvis and Me: The True Story of the Love Between Priscilla Presley and the King of Rock N' Roll. It is this new perspective the audience has come for tonight.

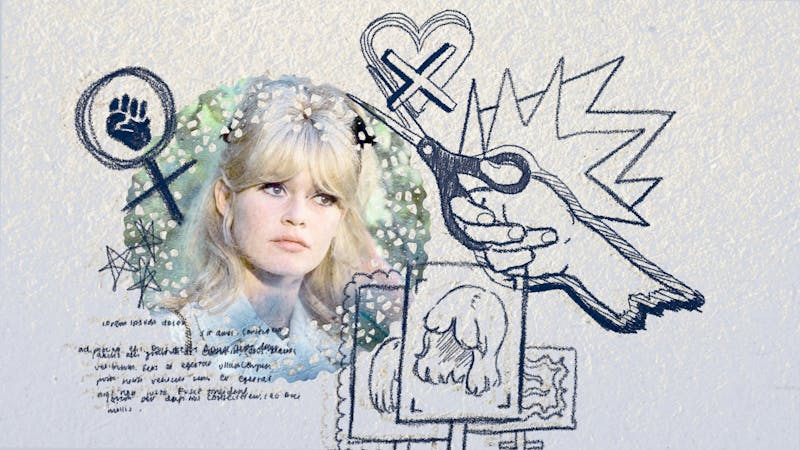

They’ve also come for lush sets, costumes, and a shirtless Jacob Elordi (Elvis). Coppola’s quintessential, almost feminine by nature attention to detail is well–established across the director’s oeuvre—from the linen–filtered light of The Virgin Suicides to the saccharine pallet of powder pinks that rule Marie Antoinette. But mostly, the crowd awaits a heroine.

In an era of Barbie and Blonde (the Marilyn Monroe biopic), audiences have come to expect quasi–feminism from any film centering women in some way—the latest blockbuster à la mode. So, bouffants held high, Priscilla in their hearts, they’ve come to witness a bonafide Elvis Presley take down.

Unfortunately, what they got was no epic redemption story. It was a simpler and sadder reality.

The film starts when 14–year old Priscilla, played by Cailee Spaeny, is introduced to 24–year old Elvis at a military social in Germany where her father was stationed. She’s pretty much hooked from the start (it’s Elvis in 1959—who among us could resist?). He gives her a kiss, they have a quaint romance, and some time later (in one of the more shocking lapses of parenting history) Priscilla is shipped across the Atlantic to live at Elvis’s Graceland. Here, she finishes high school, pines for her touring man, waits and waits (and pines) and waits some more. Her only job—Elvis makes clear—is to pick up the phone when he calls.

Trapped in a twisted Graceland Eden, young Priscilla is not allowed to get a job, play too close to the gates, or develop herself in any way beyond that which pertains to The King. When she pipes up about a song—prompted, I might add—Elvis just barely misses her head with a hurtled chair.

So, if Priscilla is portrayed as a victim in the film it’s because she is one. The abuse and neglect she faces at Graceland is nothing short of abominable, and it is true that, on this point, the film does well to shade the Elvis legacy with its own dark reality.

However, though one can blame her for being helpless, it's undeniable that Priscilla (as a character) feels too thin to make up a satisfying "woman–taking–back–her–narrative" biopic.

I myself had shown up to the theater expecting something more. I was an Elvis fan only so far as I knew the songs from my Grandpa’s jukebox and was happy enough to watch a leather–sheathed Austin Butler prance around in Luhrmann’s film a few years before.

That being so, I was not particularly attached to the man. I came to the theater pumped up on the prospect of girl power and ready to embrace a different hero. Just the idea of Priscilla—the hype of her forgotten story and the flurry of bouffants—had been enough to get me rooting for her. So, to say that her character ultimately fell short, for me, means that the film’s portrayal was beyond neutral; it was regressive.

For a story that claims Priscilla’s perspective, there is remarkably little insight into her specific thoughts, emotions, and desires—at least beyond those concerning Elvis. Proponents of Coppola’s work normally praise the emotional distance she curates as an effective aesthetic; her films celebrate the world as it exists instead of taking liberties to expose or assume a character’s inner workings. This sort of objectivity can work for Coppola, leaving her characters shrouded in a decadent mystery that intrigues rather than alienates. But in the case of Priscilla, without an inside look at the fire or fight of its starring woman, all we are left with is the shallow image of a girl in distress. Pity, not inspiration, is the overwhelming product of Coppola’s surface–centric style here.

The ending might be the most confounding and character–flattening of all. Finally divorced after six years, Priscilla drives out of Graceland. The windows are down and Dolly Parton croons from the radio. But right at this precipice, this beginning of her life as an individual—the singular Priscilla her movie proclaims—the credits roll. The movie ends. The lights come up, and suddenly, the audience’s makeup appears more cakey than playful. The bouffants have started to sag. People are tired and leave quietly. There is none of the levity they walked in with; none of the pride and none of the giggly chatter.

Perhaps it is unfair to be disappointed by the lackluster life of a trapped woman, but not every unfortunate story deserves a feature–length film.

A better expectation for the movie might have been this: Priscilla, contrary to its name, is no redemptive biopic of the life of Priscilla Presley. Albeit well–done, visually beautiful, and generally entertaining to watch, it is ultimately just the story of a woman’s sad and strange relationship with a very famous man.