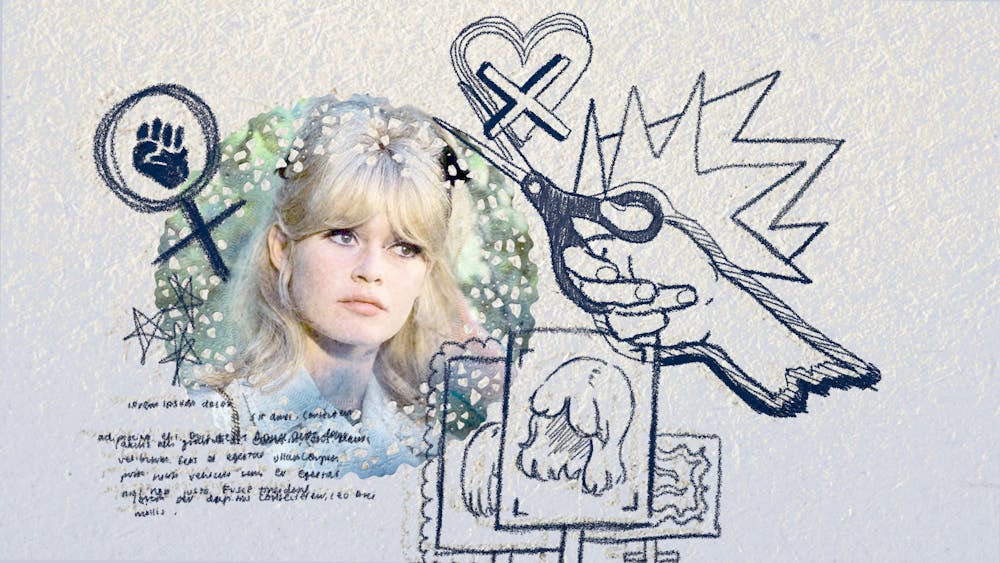

Last week, Brigitte Bardot celebrated her ninetieth birthday. In celebration, let’s talk about the icon who didn’t just make the world fall in love with her—she made the world obsessed with her.

With every role she played, Bardot seemed to dance between empowerment and exploitation, a symbol of sexual liberation who was simultaneously confined by the very gaze that idolized her. She was not just a woman on screen; she was the woman—a figure of beauty, desire, and rebellion, shaped by the film industry’s need to capture and control the female form.

Brigitte Bardot didn’t just live through the sexual revolution of the 1960s—she was the revolution. Women had long been told to hide their desires, to be good, quiet, and respectable. Bardot tore through that narrative with the force of a hurricane. She lived, on screen and off, with a kind of carefree abandon that was unheard of.

With her tousled hair, smoky eyes, and that effortless je ne sais quoi, Bardot became the poster girl for carefree sensuality, a look that would evolve into the cigarettes and red lipstick “French girl chic” heralded by Vogue. Bardot defined a style that was entirely her own: “I was never fashionable!” she laughed, “because I was never trying to be.”

Before Bardot burst onto the scene, teenage girls were nowhere to be found in public life. They were either tucked behind the hem of their mother’s skirts or awkwardly trapped in the transition to womanhood, an awkward neither here nor there. Enter Bardot: tousled hair, languid gaze, and a wardrobe that didn’t care about the rules. She was seen as neither child nor woman.

With Bardot’s arrival came the birth of the jeunes filles phenomenon. Suddenly, the world was filled with girls who refused to grow up too fast, yet embraced the seduction of womanhood without apology. Bardot’s style—her effortless, “I woke up like this” look—was copied by women everywhere. She created a new type of femininity, one that was as wild as it was innocent. She didn’t just wear clothes; she made clothes part of her attitude. Loose sweaters and perfect yet effortless curls became the armor of a generation of girls who wanted to live a little more recklessly. She invented the in-between, a liminal space for girls that was youthful and feminine.

Her style—most notably, the iconic Bardot neckline—became a symbol of this sexual freedom. But, as with everything Bardot touched, this liberation was a double-edged sword. Her body, no matter how freely it was displayed, was still being consumed by the public. The world may have adored her freedom, but it adored her body even more.

It’s impossible to mention Brigitte Bardot without And God Created Woman—the film that turned her into an international sensation. Directed by her first husband, Roger Vadim, the film was a cultural earthquake, shattering the delicate norms of the time and launching Bardot into a stratosphere of fame she would never fully come down from.

In the film, Bardot portrays Juliette, a young woman whose unapologetic lust for life, love, and sex disrupts her conservative small-town milieu. Juliette wasn’t merely a character; she was a manifesto—an embodiment of everything women had been told they couldn’t be: unashamed, sexual, and entirely their own. This made Bardot a force of nature; as feminist icon Simone de Beauvoir would later write in Brigitte Bardot and the Lolita Syndrome (1959), she was “the locomotive of women’s history.” This wasn’t merely a compliment; it was a recognition of the kind of womanhood Bardot represented—indifferent to judgment and utterly untethered from societal expectations.

Vadim once famously said, “She’s just being herself,” as though Bardot wasn’t acting at all. But the real question is: Was Bardot ever truly herself on screen? Or was she always performing a version of herself, one that directors like Vadim molded to fit their vision of feminine rebellion?

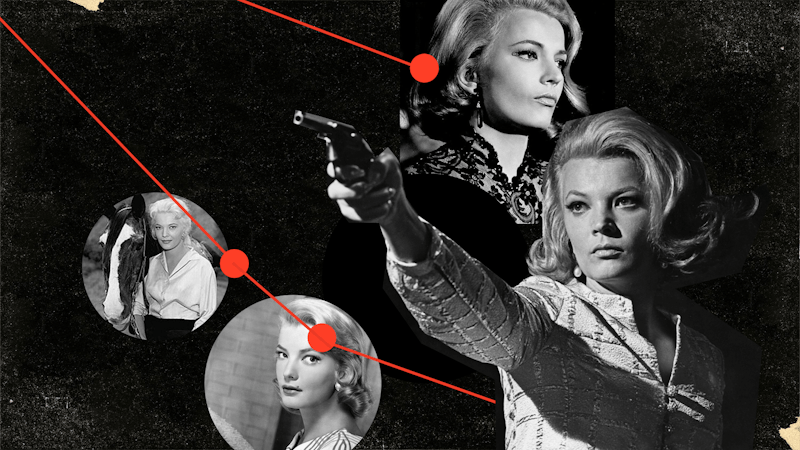

In La Vérité, Bardot portrayed Dominique Marceau, a woman on trial for the murder of her lover. Dominique is not the embodiment of freedom that Bardot had become famous for, but rather a woman trapped—consumed by passion, jealousy, and a desperate love that drives her to murder. It’s a performance that strips away the effortless sensuality Bardot had come to represent, revealing a much darker, more complex side of both her acting and her on-screen persona.

Bardot wasn’t just a symbol of carefree sensuality—she could embody the very opposite, portraying the destructive nature of passion. La Vérité challenges the notion of freedom itself, asking whether the pursuit of desire always leads to self-empowerment or, in some cases, destruction. Bardot’s Dominique is both victim and perpetrator of her own unraveling, a figure consumed by unchecked emotions. She reminds us that liberation is not always a triumphant, glamorous journey; sometimes it’s messy, dangerous, and tragic.

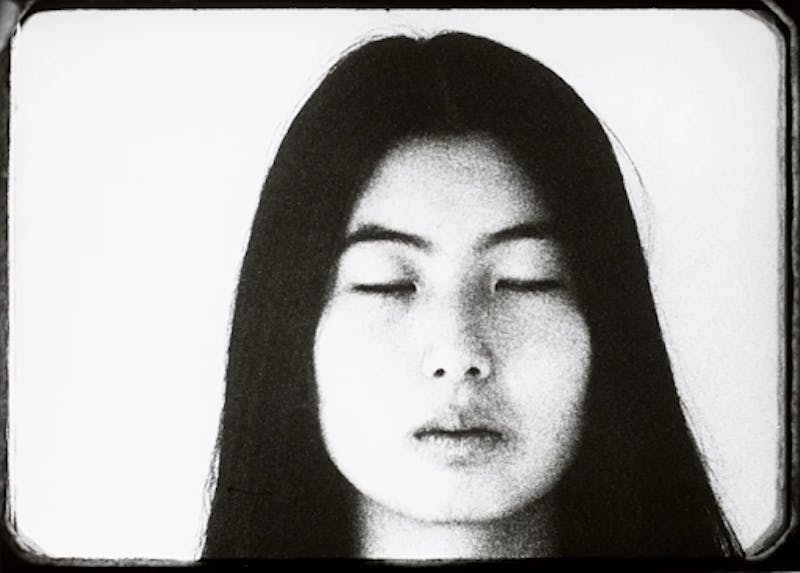

In Le Mépris, Bardot inhabits what is arguably her most complex role, cementing the film as a cornerstone of her legacy. Directed by Jean-Luc Godard, Le Mépris is a study of how women are reduced to objects, fragments of desire for others to interpret and manipulate. Bardot’s character, Camille, is caught between her husband’s lofty artistic aspirations and the commercial demands of a Hollywood producer. She exists in the spaces between art and commerce, between muse and object, between the gaze that seeks to possess her and her own desire for independence.

The film’s iconic opening scene is nothing short of haunting: Bardot lies naked in bed, asking her husband if he loves each part of her body—her legs, her lips, her eyes. Godard’s camera doesn’t merely linger on her; it dissects her, fragmenting her into pieces meant to be adored but never fully understood.

As the film progresses, Camille’s silence becomes more deafening. She retreats into herself, almost as if she’s receding from the very image that the world has constructed of her. This silence can be interpreted in two ways: as an act of submission to the forces that objectify her or as a subtle rebellion—a quiet refusal to engage with the narrative imposed upon her. It’s a silence that feels like a form of liberation, not from the world but from the gaze that has imprisoned her. Camille's withdrawal from conversation, and eventually from her marriage, mirrors Bardot’s own retreat from the spotlight years later—a refusal to be confined by the expectations of others.

What makes Camille—and Bardot by extension—so compelling in this role is the space between being the subject of the male gaze and transcending it. While Godard’s camera fragments her, the myth of Bardot as merely an object of desire begins to disintegrate. Her silence and eventual disappearance from the film suggest that true liberation might lie in becoming unknowable, in refusing to participate in the narrative at all. But beneath that allure lies a troubling reality: women seldom control their own stories. This raises a complex question: is stepping outside the frame an act of empowerment, or is it simply another form of silent erasure and acceptance?

For Camille—and Bardot—this ambiguity becomes their form of agency. By becoming an enigma, Camille defies being pinned down, slipping beyond the male gaze’s reach. Yet, this withdrawal from the world could also be read as a kind of quiet resignation, a refusal to participate in a narrative that won’t allow her full subjectivity. It’s this tension—between presence and absence, rebellion and erasure—that complicates the idea of liberation. Camille exists in the space between, embodying both freedom and the danger of disappearing entirely.

Bardot wasn’t interested in playing the roles society had set out for her: the good wife, the dutiful mother, or the demure woman. She didn’t reject societal expectations out of defiance—she simply lived as if they didn’t exist. Quiet indifference was revolutionary.

The intellectual elite was utterly fascinated by this indifference. Writers like Marguerite Duras and Françoise Sagan found Bardot’s refusal to apologize for her own success nothing short of intoxicating. While other women bowed under the weight of their fame, Bardot stood tall, unaffected by the adoration or the scrutiny. In a world that demanded humility, Bardot’s audacity to simply be—without explanation or apology—was nothing short of scandalous. She became a paradox: a figure adored for her beauty and sensuality, but equally feared for the power she wielded in her refusal to care what others thought. Bardot’s beauty wasn’t passive; it was a weapon, a statement, an existential threat to the very norms that tried to cage it.

For the intellectuals of her time, Bardot wasn’t just an actress—she was a concept. She represented the collision of desire and fear, of freedom and constraint. And in her indifference to all of it, she claimed a kind of power that was both liberating and unsettling, an unapologetic freedom that made the world take notice—whether it wanted to or not.

Brigitte Bardot remains an enigma—a woman who embodied sexual liberation but was trapped by her own beauty. She was both a muse and a cautionary tale, a woman who was adored by the world but perhaps never truly understood. Bardot’s strength as an actress lies in her ability to make us believe in the illusion of her freedom, even when we know that freedom was always just out of reach.

After the cameras stopped rolling, Bardot turned to animal activism and dreams of anonymity. Stardom had made her reluctant to even eat outside of her home. Men were unable to see her for more than a beautiful still frame and she confessed to never feeling beautiful. She spent her days bankrolling conservation programmes, fighting against fur coats, and tending to her goats in sunlit St. Tropez.

Bardot herself summed it up best: “I have been very happy, very rich, very beautiful, much adulated, very famous—and very unhappy.”