Late July afternoons in Athens, Greece are sweltering. Tourists choke the narrow streets, the pavements steam with a dense heat. The cool white basement of the Contemporary Greek Art Institute, tucked discreetly behind the central Syntagma Square, provides a welcome relief. For the first time, the National Gallery has sponsored an exhibition here, introducing the works of the Korean–American writer and artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and placing them in dialogue with Greek artists.

The exhibition seems to deliberately not market itself as a retrospective on the life of Cha, who was violently raped and murdered in 1982. Instead, the focus is on reverberations of Cha’s work—cued by the exhibition’s title, The Poem Returns as an Echo—in the projects of Greek female artists today. Cha’s brutal death is never far from the opening of any writing about her. Cathy Park Hong, who devotes a chapter to Cha in her autobiographical essay collection Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, writes that the death, “saturated my reading of ‘Dictee’ [Cha’s magnum opus]” and “gave the book a haunted prophetic aura.”

Perhaps the exhibition is pushing against this overshadowing of Cha’s life with her death, especially given that, according to Caterina Stamou, the curator of the exhibit, Cha's death didn’t actually boost her recognition compared to other artists whose deaths are frequently discussed, like Sylvia Plath. “The death did not create a myth around Cha’s name, probably because her own art practice was very elusive—it was difficult to grasp for the time in which it was born,” Stamou says. “To a certain extent, the way Cha handled issues like displacement and immigration was ahead of her time.”

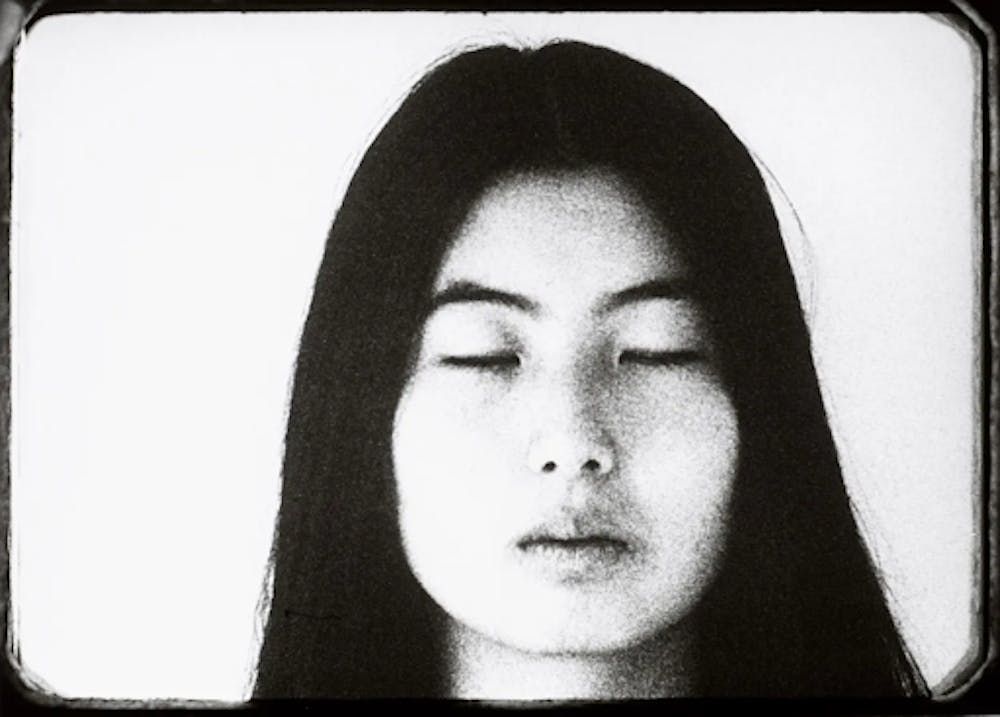

Stamou traces Cha’s artistic focus on displacement to the writer’s intergenerational experience during the Japanese occupation of Korea, in which Korean culture, history, and language was actively being erased. Cha’s family was forced to move many timesto escape the occupation. They first moved to Manchuria—where her mother had been born— then to Seoul, next to Busan, then back to Seoul, and then Hawaii. Finally, the family settled in San Francisco. This level of personal detail cannot be gleaned directly from Cha’s art as she approaches overarching themes from a metaphorically sense and she represents, "displacement through shifts and ruptures in the visual and linguistic forms of her works." For instance, her film Permutations is a silent ten minutes that consists solely of flickering images of a woman’s face—Cha’s sister—eyes closed, then open, until the final frame, when the face of Cha’s sister is displaced with Cha’s own face.

This film is projected in a nook of the Contemporary Art Institute’s basement. Despite its simplicity and its lack of color or sound, I watch many exhibition visitors unable to step away. The series of images is a series of confrontations, first with Cha’s sister, then with Cha, and finally with oneself. I make piercing eye contact with the woman projected—when she closes her eyes, I feel that she is asking a question of me, although I am not sure what the question is. This is one of the pieces that brings to mind Hong’s use of the word “haunting” to describe Cha’s work.

Her book Dictee, published weeks before her death, tells the story of Cha and her mother, melding elements of history, poetry, feminist writing, and autoethnography to such an extent that bookstores at the time struggled to categorize it. Cha invokes Greek mythology, specifically the nine muses, Sappho, and the myth of Demeter and Persephone, as well as incorporating sections of untranslated Korean, French, and Chinese. Dictee’s formal innovation and experimental style makes for a challenging read. A plot line isn’t easily traced, and it’s not always clear who’s speaking. This intentional ambiguity and staccato syntax can be seen as rendering the experience of having trouble speaking, reflecting Cha’s experience of learning English when she immigrated to the United States at 11 years old.

Cha’s 1975 performance piece Aveugle Voix feels like a message from Cha’s girlhood self of her struggling to speak. Cha sequentially bound her eyes and mouth with fabric bearing the words VOIX (French for “voice”) and AVEUGLE (French for “blind”), before unfurling the scroll bearing the words “words / fail / me ” and “aveugle / voix / sans / mot / sans / me” (blind / voice / without / word / without / me). If the viewer reads from the bottom, from the top, or in the order that the words appear, the meaning of the lines changes. “How is one muted through the eyes, blinded by the mouth?” asks reviewer Hiji Nam writing for Art in America.

Attempting to synchronize all these meanings challenges the viewer. Like Dictee, Cha’s performance pieces are not made to be easily digestible or simply explainable. Speaking about her work, Cha once said: “I want to be the dream of the audience.” My experience of Cha’s work is in fact like the experience of a dream: Images and narratives are difficult to extract yet leave a powerful aftereffect that I am without the words to articulate. Cha often used gauze in her performances to separate her space from the audience. Stamou believes the gauze was also a metaphor for the inability to see clearly, and she has hung swathes of gauze from the basement’s ceiling, adding to the surreal quality of the exhibition.

Questions around the ambiguity of language are aplenty for me personally, as the exhibition tour is conducted in Greek and my experience is mediated by my translator Dimitra Ioannou, who is one of the exhibit’s participating artists. For the exhibition, Ioannou contributed a series of three collages out of three verses of her 2014 poem “Don’t Make Me Tell You Again That What You Say Will Always Be Heard.”

Ioannou tells me, “The poem describes the process of speaking out, reflecting, uttering, and echoing. The collaged poem becomes concrete language, a kind of sign that might or might not be read. Small vintage fonts and sheets of paper are repurposed to advertise meanings. ‘The present tense is a way of self–distributing.’ The not–otherwise–specified character is responsible for her own language.” Ioannou, like Cha, seems to be influenced by the aesthetic ideals of concrete poetry.

Concrete poetry is a form of poetry that emphasizes the visual arrangement of words and their typographic display. The layout of the text on the page is crucial, part of the meaning of the text itself. As in Ioannou’s poems and Cha’s Aveugle Voix, it is typical for the text in concrete poetry to deviate from the traditional linear reading patterns, blending literary and visual art. Cha frequently blended genres: “It was characteristic of Cha to take the thematic and formal approaches developed in one medium and reinterpret them in another; elements of film and video, for example, find their way into artist’s books and vice versa.”

During the course of the tour, I spoke with another of the participating artists, Athina Koumparouli. She contributes multiple sculptures from her series “Heal not Repair,” which consists of partially broken glass objects. Her website describes the sculptures as “[f]amiliar objects that have been traumatized in a moment of happiness or misfortune. Either way, they carry that moment with them. Since a traditional restoration intervention would erase the traces of memory, the objects are treated in such a way that the trauma is visible. That moment has defined them and the event has been imprinted on them.”

Koumparouli uses beeswax to bridge the glass cracks, which she says she chose for its malleability and potential to support unstable structures. “The ideas of loss and sorrow and also the concept of trauma,” Koumparouli says, connect her work to Cha’s. Koumparouli intends for her sculptures to have a metaphorical aspect, conveying the message that even if the trauma—the cracks in the glass—is visible, it does not mean that there has been no process of healing. When she’s not creating art, Koumparouli works in conservation, spending time in landscapes that are “traumatized and in transition.” Her love of the natural world is evident in her respect for bees and the beeswax they produce; “The work of bees is solitary work: slow and demanding, ” she says.

In my hours spent at the Contemporary Greek Art Institute, the themes that define the exhibition come to life. The artists I speak with translate the principles behind their works from the visual to the verbal, and these words are then translated from Greek to English. The experience is reminiscent of Cha’s work itself.