To the surprise of pretty much no one who has ever met me, I was a deeply annoying child. I self–identified as an old soul. I was heavily involved in a slew of campaigns for local politicians. And I loved nothing more than to tell fans of a movie that the book was better.

Though I’ve grown out of most of my annoying tendencies, that last one is something I’ve never quite been able to shake. Generally, I stand by it—the book usually is better than the movie. But maybe I’m just saying that because, more often than not, I’ve read the book before I’ve seen the movie. Or maybe I’m just stuck in my old ways—there are a lot of lists titled “Movies that are better than the book,” according to Google. Some top hits include The Notebook, Fight Club, and Jurassic Park. As I’ve seen all of those movies and read none of those books, lists like those are entirely useless to me. (They make me wonder, though, what came first, the stamp of quality or the market success? I didn’t even know The Notebook and Jurassic Park were books at all before today.)

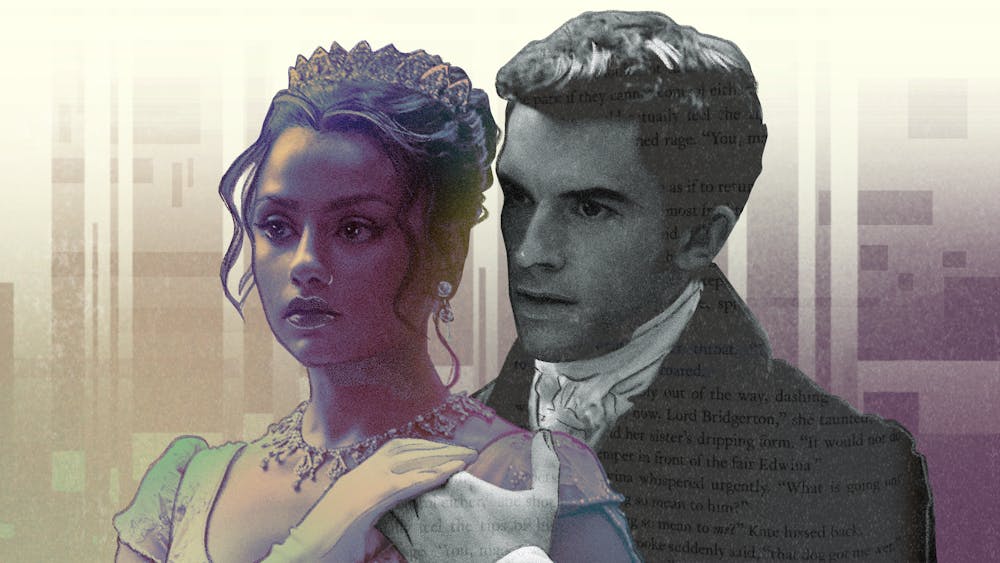

Instead, I’ll look at an example more modern, more pressing, and certainly more intellectually stimulating: Bridgerton.

“But Isaac,” I can hear you asking me, “surely you don’t mean to tell me that, despite spending your summer doing research for your thesis, juggling three jobs, writing for both this wonderful publication and The Daily Pennsylvanian, and attempting to navigate the full–time struggle of being a New Yorker living in Los Angeles, you still managed to make time to read the Bridgerton books? Even though you actively dislike most romance novels?”

Of course I did, dearest gentle readers. Of course I did.

I’m currently on book five—Eloise’s story, titled To Sir Phillip, With Love, which, for what it’s worth, is an absolutely bonkers novel so far—but of the past four books, I’ve only actually enjoyed one: book four, the Colin and Penelope story that was the basis of this recent third season of the television series. It’s a story that’s been the subject of a lot of hot debate online through the lens of how adaptations should operate.

From its inception, Bridgerton as an adaptation of the book series has always sparked digital discourse. Most of the discussion is not–so–thinly veiled racism from people who are upset that Shonda Rhimes made the world of Bridgerton a modernized interpretation of the Regency era, casting actors of color in many of the lead roles, whereas all the book characters are white. These arguments are stupid, and so are the people who make them.

But there are other changes seen in the onscreen Bridgerton adaptations that merit discussion. The specifics of Anthony and Kate’s engagement, for one, underwent serious rewriting. In the books, they are entrapped into an engagement because their mothers catch Anthony trying to suck the bee venom out of a sting Kate receives on an exposed bit of her chest (yes, really, romance novels are this goofy and horny). In the series, there’s some love triangle business that not only do I think is better (I love love triangles! So sue me!) but is also just practical, considering that, last season, Simon and Daphne were entrapped into an engagement for reasons involving scandal and propriety.

There are changes, like this reworked engagement, that are made for the sake of logistics. We don’t want to do two entrapments in a row. However, changes that are made for character or tone reasons is where things can often get dicey. Look at Colin and Penelope; in the book, they have a confrontation because Penelope reads Colin’s writing, which Colin is insecure about. In the show, the same thing happens, but with the alteration that this time, the passage is a pretty salacious one. It’s a change made to Make Bridgerton Sexy Again (fans were mad after there was a longer wait for the couples to start hooking up in seasons two and three versus season one). But it misses the point of the conflict in the book, which is not that Penelope feels some sort of way about Colin hooking up with Grecian girls, but that Colin and Penelope both struggle with feelings of jealousy about the other’s relationship to writing.

So should the show have kept fidelity to the book? In that instance, yes. But what’s missing isn’t an argument about writing. What’s missing is the messaging and themes behind that argument. That’s what an adaptation should hold fidelity to—the details don’t matter.

A much larger example is The Perks of Being A Wallflower, of which I feel like I might be the only avid hater. The book is a slow, aching traipse through the life of the main character, Charlie, and ultimately is about the impact that his aunt’s molestation of him has on how he interacts with the world, his peers, and women. Whereas the movie is a coming–of–age Emma Watson/Logan Lerman vehicle that also happens to include sexual abuse. The details, again, are irrelevant—it’s the buzzy casting, the atrocious American accent, the Ezra Miller, the tacked–on–at–the–end molestation reveal that makes Perks a bad adaptation. It loses the ethos of the novel, and it loses the novel’s perspective and approach.

And then there are projects like American Psycho, where it’s arguably impossible to even judge the book and the novel in the same way. They’re apples and oranges. The book was written by a gay man and centers masculinity and its aversion to gayness in an undeniable, central way. The author is also quite certainly a misogynist, and it creeps into the novel, even when the novel is trying to illustrate how harmful and violent misogyny and its role in constructing a model of hegemonic masculinity can be. The film, on the other hand, was written and directed by women, and it doesn’t have the same signifying motif of a fear of AIDS, for example, that exists in the novel.

Though in both cases the crisis of masculinity is framed in opposition to a fear of perceived femininity, in the book there’s a more notable focus on gay men as representing that femininity along with the women, while in the movie, it’s almost entirely women who do so. The movie also takes pains to center the female perspective a lot more. They end up being two different stories, even though they have a lot of the same details, characters, and plot beats. I wouldn’t characterize the American Psycho movie as either a good or bad adaptation of the book—it is a completely different approach and interpretation of it—something entirely different from a straight page–to–screen adaptation.

There are so many ways to approach making an adaptation and infinitely more to approach assessing the execution of one. But the most common approach of equating absolute fidelity to the details with the adaptation being well done misses the point, and it devalues the central elements and messages of the original text. Getting caught up on the details only leads to a lifetime of misery, nitpickiness, buzzkillery, and an overall CinemaSinsian attitude that benefits absolutely no one. A good adaptation doesn’t have to hit the same plot points or have all the same character names—it just has to have the same heart.