Thanks to the promises in the marketing for Longlegs, the theater was full of nervous chitters anticipating what horrible abomination Nicolas Cage was going to appear as.

A half–page in the Seattle Times featured a Zodiac Killer–esque code, ominously "printed at the request of Longlegs." Cryptic clues flooded Instagram, while phone numbers plastered across Los Angeles billboards led to eerie threats whispered by Nicolas Cage, the film's unnerving villain. A video on Youtube showed Maika Monroe, who plays the titular FBI agent, with her heart rate spiking to 170 bpm at her first sight of Cage as Longlegs.

Most damning of all were the reviews adorning the end of each trailer. “The best serial killer horror film since Silence of the Lambs," and, “The scariest film of the decade.”

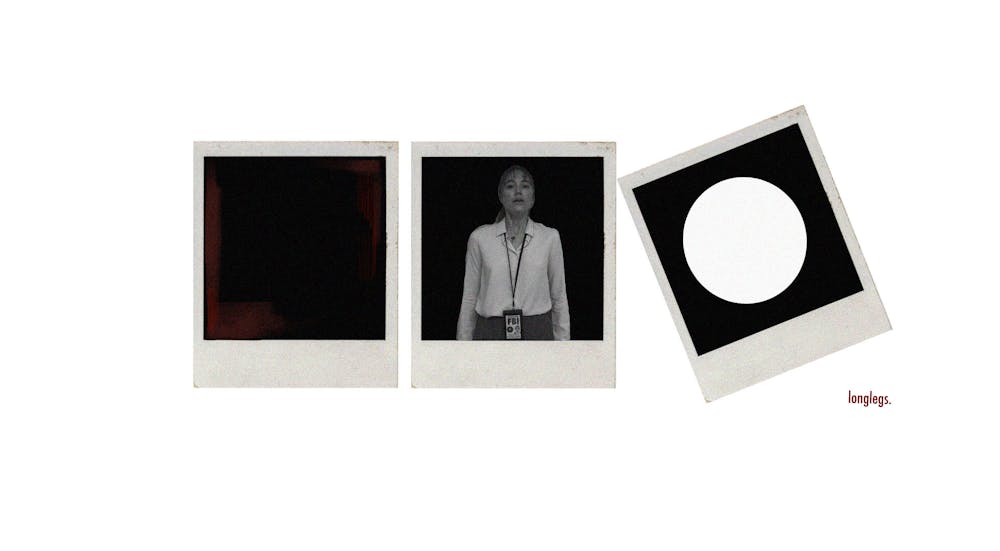

The brilliance of Longlegs' marketing lay in its understanding that true fear stems from the unseen. Despite the heavy–handed marketing, the specifics of Cage's horrifying character remained a mystery. In the video of Monroe seeing Cage, his face is blocked out with a giant black square. This ambiguity allowed imagination to run wild with grotesque possibilities, making the anticipation almost unbearable. Personally, I was convinced that watching the movie would be a harrowing experience that would rob me of sleep for days.

However, there was a stark disconnect between the marketing and the actual film. Entering the theater, my expectations were set sky–high. Yet, the film forgot one crucial element: the scares. I was on edge throughout the film. Along with the high expectations set from the advertisements, the suspiciously well–lit backgrounds at the tensest moments of the film plus expert filmmaking that maintained constant tension made me continuously brace for scares that rarely came. Instead of reflecting on the final scene or the grisly murders, I left the theater acutely aware of the tension–induced headache I had developed. While most horror films struggle to maintain tension in between the scares—resulting in the common complaint of unearned, cheap jumpscares—constant tension with no payoff leaves the audience unsatisfied.

When analyzing Longlegs outside of the context of its marketing, it is simply a decent film that isn’t really scary. The story centers around an FBI agent played by Maika Monroe, who is drawn into the twisted and grisly investigation involving a series of occult–based murders. As she delves deeper into the case, she is forced to face the sinister Longlegs, the link between her terrifying childhood and the bloody present. The film weaves elements of supernatural films and traditional crime investigation films while maintaining the undertone of dread, creating a unique story that at no point feels derivative.

Monroe's performance, particularly in the first half, left me yearning for more depth. Her constant flat, tense expression lacked the underlying emotion needed to draw the audience to care about her character, and not just the scares promised. However, in the latter half of the film, her acting was enthralling. It was then where I felt I could see her psyche evolve with each scene—even without Monroe uttering a single word. Her transformation from a stoic agent to a vulnerable victim with mounting traumas added a layer of human complexity to the film.

Longlegs was a film shrouded in anticipation and fear, thanks to its ingenious marketing campaign. In reality, it was decent with minor flaws. But the disconnect between the hype and the reality resulted in a movie that, while captivating on its own, failed to deliver the horrifying experience that was boldly advertised. The experience of preparing to watch Longlegs and the tension maintained throughout the film will linger in my mind, overshadowing the film itself.

Ultimately, a lesson learned is to not create hype–inducing marketing hinging on an aspect of the film that it can’t deliver on.