What if I told you that your neighborhood doctor, global–business and manufacturing CEOs, and an esteemed professor were once radical Philadelphia activists? Nearly 40 years ago, they belonged to an intimate community of Penn students who led the crusade against the university’s investment in apartheid South Africa. You may not guess it at first glance—they bear little resemblance to the bright–eyed teens (or “scruffy hippies,” as the now–professor and lawyer self–describes) who fought the Penn administration all those years ago—but that same fire is visible after mere minutes into speaking with each.

Polly Fraga (C ‘87) is prepared to bridge this decades–long gap. Prior to our conversation, she reaches out to several of her fellow co–organizers from her days of protest. She is inadvertently ushered back into the leadership role she took on in 1986 as a member of the Penn Anti–Apartheid Coalition, and suddenly Fraga has connected me with more alumni—scattered across the world, all eager to recount their experiences—than I’m able to accommodate.

The Penn Anti–Apartheid Coalition was the leading force in Philadelphia’s iteration of the global movement. While the university was seasoned in campus activist relations by the beginning of the ‘80s, the worldwide movement to end the apartheid regime in South Africa had yet to sweep across universities in the United States. With escalations of violence in the country, 1985 brought the cause to the forefront of American youth activism—and, ultimately, to the steps of College Hall.

“There were around 40 of us, and we actually got into [then–Penn President] Sheldon Hackney’s office, and we waited until we knew that he was going to be leaving. … We just went right in and said we wanted to talk about divestment, and that we were gonna stay,” says Fraga, recounting the College Hall sit–in which began on Jan. 22, 1986.

Among those 40 students were Stuart Rudoler (E ‘86), Deirdre Smith (C ‘88), and Deirdre White (C ‘88), who recount the 19 nights spent not in their dormitories, but rather in sleeping bags spread across the linoleum floors of the University’s oldest building.

“I remember living in College Hall for a bit. We just sort of moved in and slept on the floor for a while,” says Smith, who became involved in the efforts through the Progressive Student Alliance as a freshman.

Rudoler, one of the co–founders of Jewish Students Against Apartheid, didn’t sleep over but says nevertheless it “was certainly defining” for him. “Sheldon Hackney came out and talked to everybody and everything,” remarks Rudoler, a detail which he strained to recall.

Rudoler isn’t alone in his difficulties extracting the fine details of these events, brief in the scheme of their greater college experience. “I remember it as being about a month. What I saw [when I looked it up] this morning [was that] it was maybe 20 days,” says Fraga. “It felt a little longer, but probably what I read was exactly right.”

Sit–in in College Hall, 5 Feb 1986

The motivation for ceasing the sit–in on Feb. 11, 1986, following 20 days of futile negotiation attempts, is difficult to pinpoint. “It got smelly at the end and that was one of the reasons I think—I don't clearly remember why we decided the time was up, but we lasted there for a long time, and I remember that quite clearly,” says Fraga.

While recounting the events of the sit–in, particularly its end, it’s evident that this was a moment of refocus, rather than defeat, for the assembly of student activists. Speaking to The Daily Pennsylvanian on the day the protesters vacated College Hall, White, a former DP opinion writer herself, stated “We’re not retreating, but taking time for a strategic redeployment to decide what the next step should be.”

The events that followed the sit–in, the countless student rallies, street theater performances, and protests, appear small in the context of the greater global movement. But by no means were they insignificant: They even earned the young Penn students recognition from Bishop Desmond Tutu, who won a Nobel Peace Prize two years prior for his anti–apartheid activism.

After speaking to the greater Penn public, Tutu arranged for a personal meet–and–greet with roughly 150 students, all of whom had worked in advancing the campus movement. Tutu expressed that he “wanted to touch some of those Americans who were working so diligently on behalf of his countrymen and say ‘thank you’.”

“It was one of the most powerful days of my life,” says White. “To have someone of his stature standing there with these students who had taken some actions that were certainly nothing compared to what a lot of people have to put forward … and to tell us all that it really does make a difference, I think was extraordinarily powerful for me and for all of the people in that room.”

There’s a difficult balance in placing American student activities into the context of the greater success that was the anti–apartheid movement, a period of civil resistance which amassed for decades. White says “Victory in that movement belongs to the South African people, and the tragedy and the loss and the courage that it took belongs to the South African people.” Simultaneously, though, each former activist acknowledges the significance of global pressure in bringing about the eventual end of Apartheid.

Fraga echoes similar sentiments, saying “I can't say Apartheid maybe would have ended anyway, but the pressure from the U.S. [sic] and the international community, the business pressure, it had to help. It had to help. And so I like to think it made a difference.”

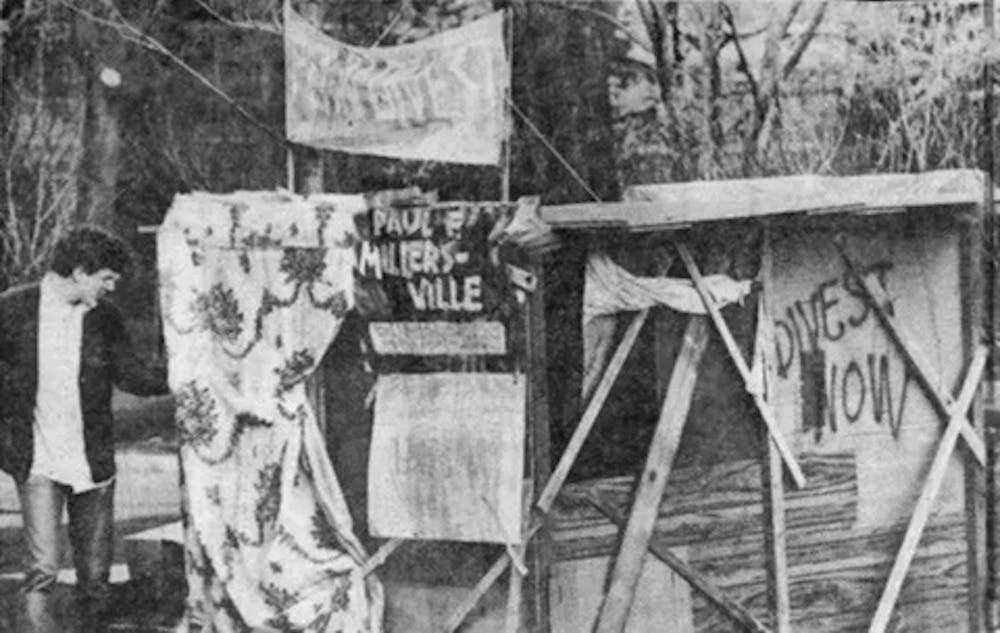

While the global campaign to eliminate these legacies of colonialism focused their energies on the white supremacist government of South Africa, these Penn students found their opposition on domestic soil. The students set up a "shantytown"—a protest tactic popularized by students at Columbia University—and named it “Millersville” after the then–Chair of the University Board of Trustees, Paul Miller. They had been well–aware that their primary targets were the moneyed interests of the school.

From the administration, “It was always a big no,” Fraga says. “The trustees were not, and did not, appear to be sympathetic.”

1986 Shantytown at Penn, “Millersville,” Courtesy of Penn Libraries Archives

The source of much of the contention between the Coalition and the University’s overseers was the Sullivan Principles, a guide on the treatment of workers under the apartheid regime developed by Rev. Leon Sullivan a decade prior. Many university administrators, including those at Penn, as well as then–President Ronald Reagan, defaulted to these principles while managing business dealings with South Africa. The principles, however, failed to actually call for the end of Apartheid directly or for Black political rights.

“I think a lot of people felt that the Sullivan Principles were working and it was better to do change within the system, or that divestment wouldn't make a difference, or that it wasn’t really the students’ place to address it, or that Penn should make as much money with their endowment as they could—that was their mission, and not to think about social investing or just apathy,” says Fraga.

Smith echoes Fraga’s frustrations with the standoffish attitude of the administrators, stating “Wharton just felt very domineering. I felt like they captured the Board of Trustees, and the administration was very middle of the road. Sheldon Hackney was no grand progressive, and he was okay, but nothing special.”

The disputes with the Board of Trustees came to a climax later in February of that year, when White, among several other students, filed a lawsuit against the University for their failure to comply with the Sunshine Law, which dictates rules around opening meetings to the public. “The reason we [filed the lawsuit] was because the Trustees were being so secretive of the meetings around divestment, and we were trying to figure out how we could access those meetings,” says White.

“[The lawsuit] was a really important evolution in the protests,” White says. “It was a way of showing that, beyond civil disobedience, there was a clear legal path to follow, to be able to push some of the pressure levers on the University.” While it was ultimately dropped by the student plaintiffs, White’s comment is apt—the suit brought against Penn increased media attention to the local cause, both on and off campus.

With the benefit of 40 years of distance, however, each alumni expresses greater sympathy towards the administration they once (quite literally) turned their backs to. None believe the Trustees, nor Hackney, were opposed to the ending of Apartheid but that they were rather less concerned with Penn’s role in it. “Probably the administration’s concern was more the public relations side of things and the Trustee relations,” says Smith.

After her graduation from Penn, Fraga would coincidentally attend the same church as former Penn President Hackney. “I remember having a couple of conversations with him and realizing he was not the enemy. He was a leader at an institution that needed to change,” she says.

For Rudoler, the post–graduation shift extends beyond sympathy and into partial agreement. “There were Trustees who honestly believed that you would hurt more [people by divesting] and looking back on it now, I can't say that they were wrong,” he says. “I don’t want to sound like an old man. But when you’re young, it’s easy to reach for simple answers, right? … I’m not saying divestment was wrong; it’s not my opinion. I’m just saying I don’t think I appreciated the argument on the other side.”

Playwright George Bernard Shaw said “If at age 20 you are not a communist, then you have no heart. If at age 30 you are not a capitalist, then you have no brains”—a statement that (while its truth is deeply objectionable) seems fitting in the reflections of the former student activist.

For others, revisiting the period in their lives—even in conversation with a total stranger—is pure nostalgia. “It was a very exciting and formative time, I think, for me and for those that were involved,” says Fraga.

While they each apologized at one point or another, believing they had misremembered a name or date, there’s a startling clarity of these few months in 1986 in the minds of these former Penn students, none of whom have continued their activism as a day job. For those of us who strain to remember what we had for breakfast yesterday, Smith’s recollection of the plot of a street theater performance (a spoof on an advertisement by a company invested in South Africa) or Fraga’s play–by–play of the College Hall invasion are feats of memory. More importantly, however, they’re testaments to the period’s impact on the participants.

Street Theater by Coalition's “Wheel of Fortune” spoof on Trustees, 13 Oct. 1986

As the four alumni each log onto Zoom to individually recount their days on Locust Walk, anxieties surrounding the ongoing tug–of–war between pro–Palestinian student activists and University administrators hang heavy in the air. The protesters, past and present, recognize the parallels, regardless of their stance on the matter. “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” as Mark Twain said.

In the place of Millersville is the Gaza Solidarity Encampment, erected days before we speak. “For me, it was very interesting to hear from you, because it’s hard not to reflect on my own experience when I’m observing what’s happening on campuses today. It’s impossible not to think about it and not to compare it,” says Smith.

Beyond the commonalities between the two—apartheid, pseudo–shantytowns, sit–ins, and subject matter fraught with the legacies of U.S. foreign policy—Smith and Fraga are, too, struck by their divergences. “The biggest thing that is sad for me to see is how much conflict there is between students. Students either agreed with us or they ignored us,” Smith says.

Fraga resonates with this, saying “It’s apartheid, everyone thought it was bad—whereas with the Israel–Palestine–Gaza thing, there are many people hurting and many people with different positions on the same campus.”

For White, the violence inflicted by universities upon their own students is made all the more troubling by having been involved in the tense but ultimately fruitful negotiations with Penn four decades prior. “I watched with my blood curdling, the riot police climbing that ladder into Columbia University the other day,” she says. “They could have handled this without riot gear and the kind of equipment that’s used for armed insurgencies. I’m really disappointed in Columbia University for bringing in the NYPD at that level of force.”

She notes that, despite their unwillingness to come out into the open about their investments in South Africa, the Penn administration and the Board of Trustees did not forcibly remove the students from College Hall or threaten the students with suspension or expulsion, nor did they “send in riot police,” says White. “No knee–jerk reactions, no police, no nothing.”

Celebrations of Penn’s alumni arrive with all things shiny—prizes, lofty titles, positions, achievements, and activism—though only the palatable kind. They are invited to speak at commencement ceremonies or to cut a ribbon if their pocketbook happens to fall in the direction of a new building. Or, perhaps, they too will teach at the school.

But surely all alumni can’t have gotten along splendidly with the school: No hated professors? No club rejections? No questionable interactions with the Penn Police Department? Not a single protest against Penn?

Don’t be mistaken, these activist alumni are as—if not more—decorated as the last. But their greatest lasting mark on the campus they called home for those four years has not, and will not, be recognized by the University. That is, unless the school wishes to tout its self–ascribed label as the “civic Ivy.”

It’s a missed opportunity—a part of Penn’s history that’s been neglected. The sanitized portraits of familiar campus hallmarks behind a black–and–white lens can’t capture the students standing just ten feet away from the flash, shouting for the end of the Vietnam War, for the prevention of assault on the campus, for Penn to end its investments in South Africa. The truth is that student protest is not new—nor is student anger, or student disruption, or student discomfort. Their actions were considered a nuisance, inconvenient—dangerous—long before you or I arrived here. But just as chalk–written calls to action are eagerly power–washed away, so too were the remnants of their divisive, radical activities.

The modern function of these activist lineages at Penn exceeds legacy. Credit won’t be found in the footnotes but in the bold tactics and undeniable success of the previous classes of campus agitators, which continue to serve as a blueprint for demanding change at universities today. Beyond brass plaques and inscribed benches, the events of 1986 linger amongst College Green (née Millersville) and atop the steps of Fisher Fine Arts (née impromptu stage)—and in the minds of today’s student activists.