The reveal of Gossip Girl’s identity during the hit 2010s show’s series finale in 2012 was a closing door on paper, an albeit disappointing end to the anonymous figure which tormented Blair Waldorf and teen viewers alike. In real life, the domination of anonymous not–so–social media, however, had only just begun. Within the year of the show’s close, Yik Yak, ASKfm, and Whisper had wriggled their way onto the iPhone 5s of middle and high school students, bringing with them a slew of controversies in schools across the nation.

But our generation didn’t outgrow its obsession with the anonymous when the apps of the 2010s became uninteresting, it just turned to the craze’s newest iteration—Sidechat, the anonymous college campus Reddit knock–off, founded in 2022.

Identifying the leadership behind the campus phenomenon that is Sidechat is a nebulous task. At the time of the app’s founding in 2022, the creators remained anonymous. Today, we know Sebastian Gil, the CEO, as the semi–public face of Sidechat. Beyond mentions of Gil as a CEO and co–founder of the organization, Gil and his coworkers are tough to digitally trace. The app is owned by Flower Avenue Incorporated, which has also since purchased Yik Yak. Despite the app’s emphasis on anonymity, it’s become notorious among its users for its failure to do just that.

The app made private matters public for Sophia Weglarz (C ‘24), who got into an argument with another student at a party earlier this semester. “My friends posted on Sidechat about me and the girl. They didn't use either of our names, but, you know, enough identification where [she] could have easily known [...] and they sort of put that out on Sidechat, and then it just turned into a bit of a frenzy,” says Sophia.

What had been posted as a light–hearted joke among friends turned sour as users on the app commented, “‘Oh, she got what she deserved,’” says Sophia. “Just crazy things [...] like ‘so and so is a domestic terrorist.’ Very crazy things, which are jokes in nature, but are just kind of insane.”

While many of the posts, which directly identified Sophia were eventually removed, she was still struck by the ways in which the discussions of the altercation on Sidechat began to bleed into her real life. “Over the past few weeks, I have gotten some remarks like ‘Oh, my God, what happened? I saw your name all over Sidechat!’ Just random people who would come up to me,” she says. “I think the biggest power of Sidechat is something that would have just been a private moment [...] is now being aired out, and for people who would not have known, feasibly.”

Sophia’s concern over personal harassment cases on platforms such as Sidechat is echoed by Siva Vaidhyanathan, Robertson Professor of Modern Media Studies and director of the Center for Media and Citizenship at the University of Virginia. “When you have a growing platform, like Sidechat, which encourages anonymous speech, you are accomplishing to some degree, [...] both its value and its negative. It makes it a safe place to express criticisms of the powerful without risking direct personal harassment, but it also fosters even more irresponsibility,” says Vaidhyanathan, “When it comes to harassing whole groups of people or responding to particular posts with the nastiest things, including threats, it's also the sort of site where you can dox somebody rather easily and without any recourse, without any blowback. And we see it time and time again.”

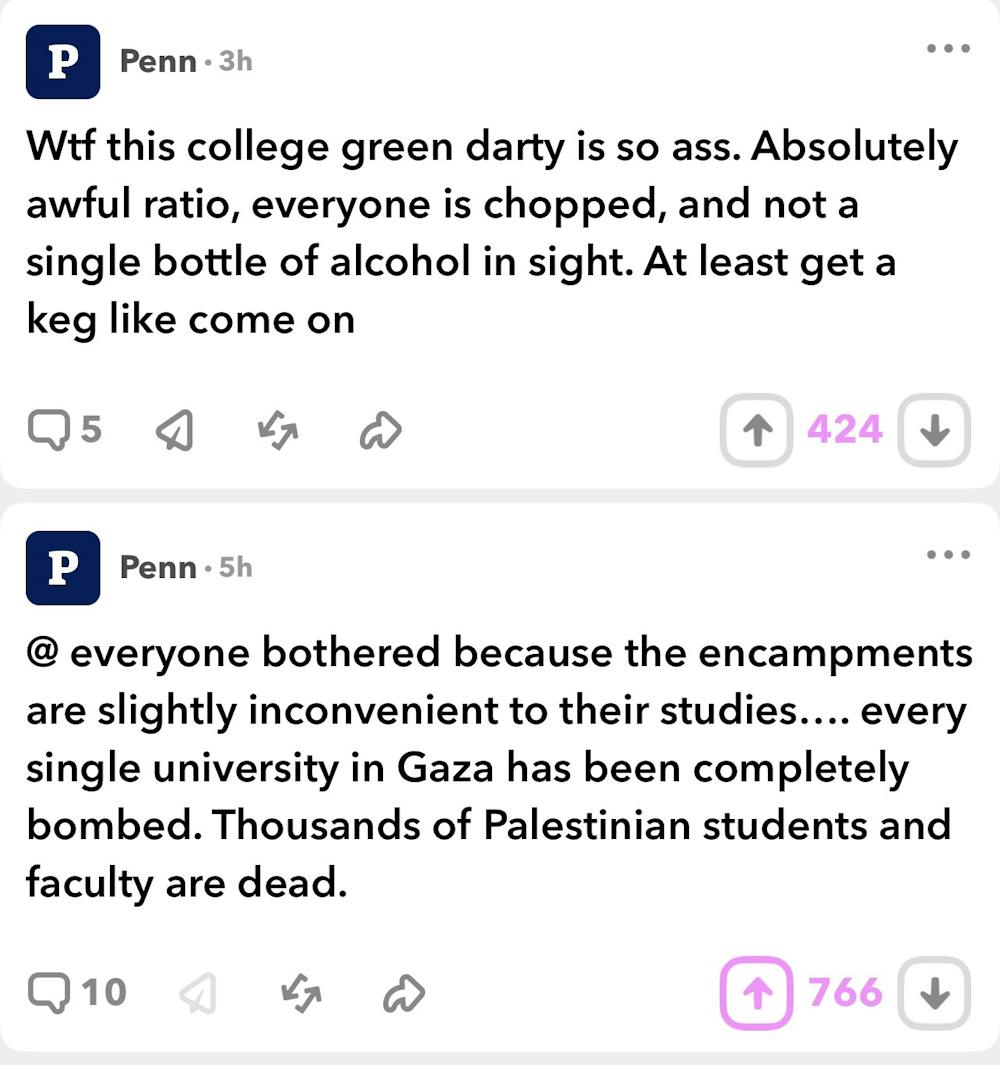

Beyond these instances of personal business being spewed for public entertainment, students like Sophia have found the app’s pessimism to be challenging. “The posts that often get the most upvotes are always ones that are quite negative. I think that's maybe a human insight—that people really gravitate to negativity,” says Sophia. “But on Sidechat, [...] you're incentivized to make jokes at other people's expense. And I think you see that with what is consistently being the most upvoted.”

While Daniel Lien (C ‘25) is a frequent user and supporter of the app, he’s open about its sour side, saying, “Oh, there's definitely days when the app is not in a good mood.”

Will Krasnow (C ‘25) remembers one of these “bad” days. “I remember that a while ago [...] people were flaming the people in the fraternity Beta. The joke was that all Beta people are short,” says Will. “And, look, I know some people in Beta and to be honest, they weren't the tallest people in the world? It's a little funny, but it's also I'm not really sure what that's doing for me, filling up space in my head. And I feel bad for the Beta kids,” says Will.

The prejudiced nature of anonymous social media that Will and Daniel point to didn’t begin with Sidechat. According to Jefferson Pooley, a lecturer at the Annenberg School for Communication at Penn and an affiliated professor at Muhlenberg College in Media & Communication, it has a much deeper history.

“There's this long tradition, even before there were such things as iPhones,” says Pooley. “In the early internet, there was quite a lot of anonymity, and psychologists early on referred to the ‘online disinhibition effect,’ where people would tend to be more vitriolic, arguably more honest, when they had a mask of anonymity.”

Pooley references the Oscar Wilde quote “Give a man a mask, and he’ll tell you the truth” when discussing the difficulties of anonymity. “Problem is,” Pooley says, “you give someone a mask, and they'll tell you more than the truth.”

Penn students and other users of Sidechat have done just that—something that Vaidhyanathan acknowledges. “Anonymous speech makes it that much easier to insult or create an unfriendly or hostile environment, which then, paradoxically, limits speech,” he says. “If it's an uncomfortable environment for the less powerful to express themselves because of bullying and harassment, racist or sexist or antisemitic comments, then the principle of anonymity undermines having a healthy free speech environment.”

In spite of the difficulties that come with the use of anonymous platforms, Vaidhyanathan emphasizes their importance. “Anonymous speech is a crucial element of living in a society where people are free to express themselves,” he says. “You need a certain level of acceptable anonymous speech for whistleblowers for challenging power. In many cases, the people who are least protected by society are those who most need anonymous speech. Attribution is a privilege of the comfortable, so if you really want to enhance a culture of free speech, you have to have the ability to speak anonymously.”

Striking a balance between the freedom of anonymous speech and the lack of consequences for its abusers is a Sisyphean task. Daniel and Will are friends, but their opinions on these aspects of the app differ—something which they have discussed at length. While at dinner with friends, Daniel posed the provocative question: Is Sidechat beneficial? “At least one of them didn't think it was beneficial because they didn't like that it was anonymous. But then I said, ‘First, I think it's beneficial to me because I'm interested in the responses that people give, just out of curiosity, but second, I don't think that it not being anonymous or it not being there at all would mean that people [would] fill the gap by being more open in what they think.’”

Daniel raises the idea that the app allows for conversations that are normally avoided in person, namely those relating to politics. He worries that without Sidechat, topics like politics wouldn’t be discussed at all.

While there are merits to having forums for these political discussions, the incognito status of users puts a strain on their productivity in practice. “People sometimes don't like anonymous political fights. And I see why,” says Daniel. “They mostly don't really produce a lot of positive growth on either side, but because these are Penn students, I think I'm much more interested just to see what people think.”

It’s this campus exclusivity which appeals to the Penn student body. If you want to hear the opinions of the general public, you’d go to Instagram, or Twitter, or any other open platform—not Sidechat. While you may hear the hot–takes of the loud–mouth finance bro in your PPE lectures more often than you’d like, it’s rare that you truly have an opportunity to hear what your peers are thinking at large. That Sidechat post with hundreds of upvotes complaining about construction in the Quad might be the quiet freshman who’s next to you in Houston, or your math TA.

Just as Sidechat didn’t invent anonymity, it also isn’t the first platform to restrict its user base to the college campus. During the early days of Facebook’s operation, the platform, which began at Harvard University, required users to register using their college email address, as Vaidhyanathan and Pooley mention.

Beyond personalizing the user experience for college students, according to Vaidhyanathan, limiting sites to “.edu” serves two purposes: creating demand—“if you were at BU, you would hear about Harvard and MIT students using this thing and you'd be jealous”—and managing growth—a problem earlier sites such as Friendster encountered.

Operating within the campus, however, has continued to raise issues for these sites. “The first few iterations [of Facebook] ran within Harvard, on Harvard servers, but they quickly got out of Harvard. They knew it was trouble, right? They didn't want to have to answer to the IT people and the security people and follow Harvard privacy law, privacy rules, etc.,” says Vaidhyanathan. The initial project of Zuckerberg, Facemash, was called by the university’s Administrative Board in 2003, facing complaints from the computer services department of unauthorized use of photos. With early difficulties such as these, Zuckerberg’s new platform felt the pressures that came with university limitations.

The decades–long dispute over the regulation of social media sites on campuses has reared its ugly head with the regulation of political speech regarding Palestine and Israel on the app.

“It looks like the congress is going to subpoena Sidechat posts. RIP to everyone who thought it was anonymous.” was posted to r/UPenn by u/Old–Patience–4641 three months ago.

On Jan. 24, 2024, Committee Chari Rep. Virginia Foxx (R–N.C.) of the Committee on Education and the Workforce addressed a letter to Ramanan Raghavendran, chair of Penn’s Board of Trustees, and Larry Jameson, Interim President.

One section of the letter ordered the delivery of materials, including the series that related to “Penn students, faculty, staff, and other Penn affiliates on Sidechat and other social media platforms targeting Jews, Israelis, Israel, Zionists, or Zionism.”

“Why don't they just say that they should search everybody's Facebook?” says Jonathan Zimmerman, professor of History of Education at the Graduate School of Education and author of Free Speech: And Why You Should Give a Damn. “The fact that you have to use your Penn ID to get on this, they're framing that as something that's institutionally connected to Penn, but it sounds to me like it's no more institutionally connected to Penn than Facebook or Instagram.”

Beyond the fact that the University does not run the app, its ability to present any information on the topic to Congress is questionable. “The company itself might have an IP [address] of someone who posted that call and might have to surrender that information under warrant,” says Vaidhyanathan. “But Congress asking a university for something—it's just dumb, but it's also bullying because the universities don't have this information and shouldn't have this information.”

“The only thing I can think is that the members of Congress who are behind this just want to intimidate students from expressing themselves. I think right now the most dangerous threat to free speech is bullying and intimidation, especially from the extreme right,” says Vaidhyanathan.

According to Sidechat’s page on community guidelines, the major violations that will result in a post being removed, or, after repeat or extreme offenses, a user being banned include posting personal information, such as names and addresses, bullying, racism, jokes about sexual assault, seeking or selling drugs, promoting self–harm, and misinformation.

Who is in charge of the moderation on Penn’s campus, exactly? In short, we don’t know. While the moderators of other campuses’ Sidechat pages can often be identified as students at the school employed by the app, this isn’t the case for Penn—at least openly.

Daniel believes he’s had a couple of posts taken down by moderators, likely for excessive cursing, and has also taken down some of his own posts voluntarily.

Regardless of who is running the current moderation, it’s clear from speaking to Zimmerman that he believes this task should not be in the hands of Penn administrators. “I don't want Larry Jameson deciding what's so terrible in Sidechat that you shouldn't say it. I should tell you, I've got nothing against Larry Jameson; he seems like a good guy. I don't want anyone doing that. I don't think that's the role of the university,” says Zimmerman.

What exactly should be done in response to objectionable content? Zimmerman offers up a potential solution. “If Larry Jameson, or you or me, sees something on Sidechat that they find offensive, it seems to me that they have the right to say that. Which is, I think, the best solution to all these matters—not to create some sort of surveillance system, but to allow people in the community to comment as they'd like.”

Students like Sophia and Will have, consciously or unconsciously, made the choice to step off of the digital soapbox. “Agency,” Zimmerman emphasizes.

“I think it's worth asking at a moment like this, ‘do we, as a community, want these anonymous chat boards?’ If I were a student that was concerned about this, I would encourage people to boycott them. You know, how about an anti–Sidechat movement, just because on the grounds that these anonymous boards, they allow people to say anything they want with impunity and without accountability?” says Zimmerman.

Maybe the 2007 series that sparked the generational obsession of the anonymous observer holds the secret to Sidechat’s future. Ultimately, it was Dan (spoiler alert) who made the choice to reveal his identity as Gossip Girl. When students feel the app no longer serves its purpose or they simply grow tired, it will dissolve into the memories of disgruntled users.

Just as we’ve cycled through trends, we’ve also cycled through the instigators of the digital world. We crave the manufactured drama Gossip Girl put front–and–center—we’ve tried to replicate the shock of the unidentifiable narrator through Whisper, and tbh, and Yik Yak, and NGL, and Kandid, and Reddit, and wish2wish, and Tellonym, and Secret, and Fess, and AskFM, and AntiLand. But as we grew up and the topics we debated went from middle school drama to nuanced political issues, we've maintained the same naive attitude. The dimensions of real issues have been flattened into meaningless fodder for the Sidechat masses.