Imagine that a house has been in your family for multiple generations. Your parents die and you inherit the house, but it’s old and needs a lot of work. The area that you live in is rapidly gentrifying, and you receive a couple of calls from developers asking to buy the house. You refuse and start to fix the house up, an expensive and slow–moving process.

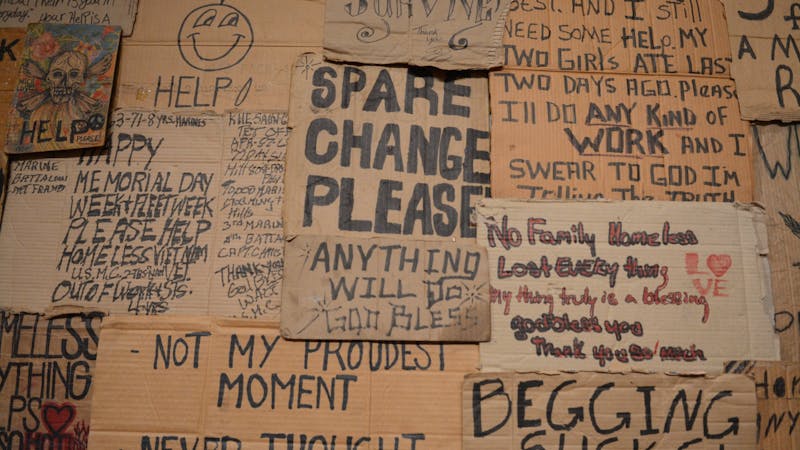

One day, you suddenly get a notice in the mail: A nonprofit has filed a petition to take conservatorship of your home. You look to fight this in court, but as a homeowner it is difficult to qualify for legal aid. Mere months later, the nonprofit wins the case and sells your house. Not only is this intergenerational property lost, but, after the mandated conservator’s fee, plus legal fees and other associated costs, you don’t receive any of the money from the sale. This situation has happened hundreds of times in Philadelphia—all due to a law called Act 135.

Act 135, otherwise known as the Abandoned and Blighted Property Conservatorship Act, is a Pennsylvania law that passed in 2008. As of February 2024, the act has been used 670 times in Philadelphia. On surface level, the intentions sound great. The law was created as a way for communities to bring beauty to their neighborhoods through remedying what is called blight. However, in November, the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School’s Advocacy for Racial & Civil Justice Clinic released a report highlighting how racialized this seemingly innocuous law really is. Philadelphia’s City Council recently held a hearing to investigate Act 135’s potential for harm.

The technical definition of blighted properties is structures that are considered detrimental, or even dangerous, to the areas that they are in. This is usually because the properties are abandoned, but also can just be because they are rundown. In a state as historic as Pennsylvania, and particularly in Philadelphia, blighted buildings are not an entirely rare occurrence.

The common consensus is that blight poses issues to other neighborhood residents, particularly in terms of decreasing their property values, but also in terms of vermin and the potential for shady activities to occur on the deserted property. An abandoned factory, for example, comes to mind. The ideal version of Act 135 would involve the neighborhood banding together to file a petition and rehabilitate the factory, turning it into something useful—such as a community center—and less of an eyesore.

But ideas that work well in theory don’t always work great in practice—especially when it comes to housing laws in Philadelphia, a city known for its gentrification problem.

The idea of blight is one that is very subjective. While it is true that a property has to meet a few specific requirements to be labeled as blighted (including that the property has to have been legally unoccupied for at least 12 months), there is still a lot of gray area surrounding what would call for a property to be filed for conservatorship. A developer likely has a very different idea of blight than someone who has lived on a block for 60 years. So who exactly gets to decide to file an Act 135 petition?

The answer casts a much wider net than one may think. Recent amendments have expanded the definition of an Act 135 conservator (or those who can file a petition). Any resident or business owner who resides within 2,000 feet of the property in question can file, as can any Philadelphia nonprofit that has, the act states, “participated in a project within a five–mile radius of the location of the building.”

Five miles is a huge radius. To put things into perspective, Penn and the neighborhood of Kensington are exactly five miles apart. The majority of Penn students likely have never set foot there. And yet, if a Penn student were to found a nonprofit and begin working on blighted properties around them in West Philly, they would be legally allowed to pick up properties in Kensington too. Suddenly, the act seems very different from the vision of residents banding together to fix up their neighborhood.

The definition of nonprofit is also a shaky one. Qualifications to file under Act 135 as a nonprofit are very relaxed. In fact, these nonprofits are actually often developers masquerading as more good–natured nonprofits. The ARC Justice report found that the primary filers of Act 135 petitions are just two 501(c) organizations—The Philadelphia Community Development Coalition and Scioli Turco. Shortly after the report was filed, the latter renamed itself to reBuilding Blocks (something that its executive director, Beth Grossman, says had nothing to do with the report).

Grossman, who began her career as a prosecutor for the Philadelphia district attorney’s office, says that her prior career experience makes her realize “how problematic properties can be.” She sees her job with reBuilding Blocks as one that largely improves quality of life for neighbors, and insists that reBuilding Blocks is a mostly referral–based organization, working only with vacant properties.

Living on a block with an abandoned building can be awful, Lizzie Shackney (Penn Carey Law '24), one of the certified legal interns with ARC Justice, acknowledges. But she thinks that if it were really about the neighbors, the petitions being filed would be evenly spread across the city, which they’re not. “They don’t match where all the abandoned properties are,” says Shackney.

Shackney and the clinic worked to create a map of every Act 135 petition filed in Philadelphia. An option allows you to color the map based on neighborhoods’ percentage of non–white residents. When this is done, it becomes even clearer how racialized this issue is.

Act 135 petitions are disproportionately filed against Black and Asian American Philadelphians, ARC Justice found. Shackney says that every single homeowner that the clinic is currently in touch with is Black.

Grossman emphasizes that reBuilding Blocks has filed petitions in every area of the city, reading out a prepared list of every neighborhood where the organization under her tenure has done work. It’s just that the largest portion of Act 135 petitions are filed in majority non–white neighborhoods, right on the line where racial demographics are flipping and where racialized gentrification is in progress. Point Breeze and Brewerytown are big examples of this, Philadelphia neighborhoods where Act 135 is thriving.

Losing ownership of a home means largely losing the ability to accumulate intergenerational wealth, something that has been denied from people of color, and especially Black, Americans since the founding of this country. “I lost a home that has been in my family for three generations,” Shane Randall, a homeowner affected by Act 135, said in a press release. “And,” he adds, “I’m not the only one.”

Since this is a Pennsylvania law, the greatest change is going to have to come at the state level. But there are a few ways that the city can begin to remedy this issue too.

Both Grossman and the ARC Justice Clinic are actually in agreement that right to counsel should be guaranteed for homeowners being petitioned, if they can’t afford it. “I never think it’s a bad idea to review a particular act,” Grossman acknowledges, adding that Act 135 hasn’t been “substantively amended since 2014.”

The Philadelphia City Council held a hearing in late March about Act 135 at which Shackney testified, along with fellow ARC Justice Clinic certified legal intern Megan Bird (Penn Carey Law '24). At the hearing, both urged council members to do even more.

The two law students have several approaches in mind to improve Act 135. A pre–service notice, for example, is one of their favorite ideas. This would allow owners to have some idea of what is about to happen to their homes, instead of finding out suddenly in the mail that their property is not their own anymore. General increase of access to home repair funding is another idea—making sure that people are able to actually afford and find the support to repair their houses, so that fewer Act 135 petitions have to be filed in general.

As students who attend a school notorious for urban displacement, housing issues within the city are ones that members of the Penn community should pay especially close attention. From the UC Townhomes demolition to the 76ers arena proposal within Chinatown, the Act 135 crisis maps onto similar predatory themes.

“Laws like this one allow for a lot of money to be made off the backs of people who are just trying to make ends meet,” says Shackney. “Any efforts that tell the city that people need to have an input into what happens to their neighborhoods [are important]. Their representatives need to listen to them.”