“Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” Ferris Bueller gave us that wisdom as a high school senior who felt he had too much on his plate. If he had gone to Penn, he’d have a heart attack within the first week. From cramming for finals to searching for internships, we seem to lack the time and the patience to think about the questions that matter most. What is virtue? What makes our lives worth living? Why are we here? On a cold Wednesday night, as crisp autumn turned to cruel winter, I made my trek through the wind tunnels of Locust Walk all the way to the Starbucks underneath 1920 Commons in search of the man who might have all the answers.

The ancient Greeks believed that above all, a man must cultivate balance to earn virtue. One must build the strength of the body while also expanding the horizons of the mind. By such a metric, Mark Hellwig (C ‘26) would seem to be Penn’s best candidate for philosopher-king. A Division I high jumper by trade, Mark’s agility and athleticism would put Athens’ best to shame. But he refuses to let himself be defined solely by his athletic prowess – an avid reader, writer and member of the Philomathean Society, Hellwig stands before us a modern Renaissance man, taking in the best every discipline has to offer.

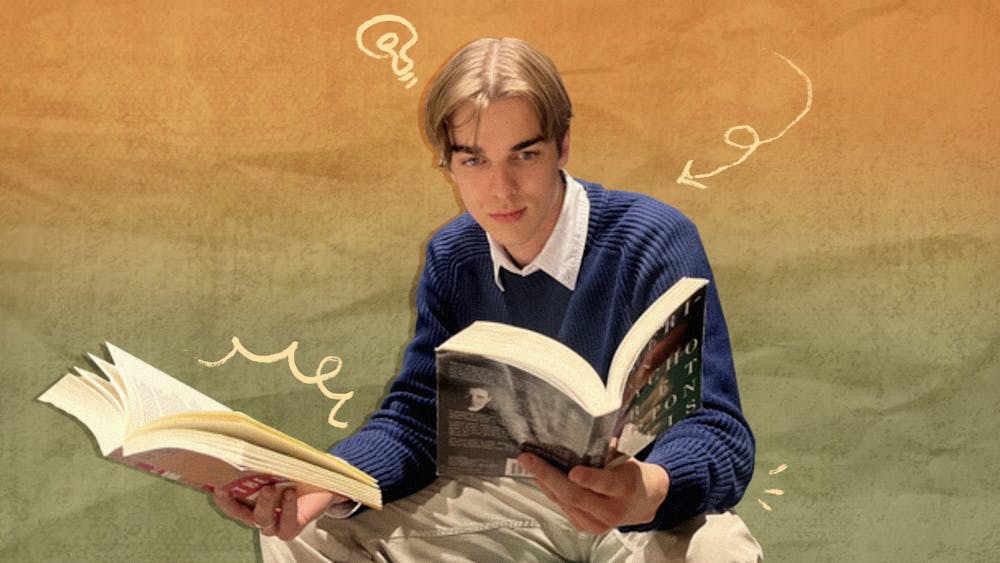

I sit down to talk to Mark on the sofas at Commons, the windows pitch dark behind him. Sporting a warm blue sweater over his crisp white button up, he wouldn’t be out of place at a coffee chat for a consulting firm. But Mark has had more than enough of that lifestyle for one lifetime. Coming to Penn hoping to get into finance, but also being interested in philosophy, Mark began his time here as a Politics, Philosophy, and Economics major “with an emphasis on the E.” In his freshman year, like many students, Mark walked a narrow tightrope between pursuing his passions in philosophy and being “employable” by building his skills in economics. That journey culminated in a real estate internship that summer–and while he found his work interesting, it was hard for him to picture dedicating his life to the art of selling property. But in his sophomore year, Mark came upon a radical new idea: doing things he liked.

More than anything, Mark was tired of trying to mold his interests and activities in a way that made him more employable.“When everything is a pragmatic decision,” he says, “there’s a little bit of your soul that’s lost in that process.” In the end, when it came time to decide, Mark decided to follow his passions and pursue a degree in English. Now, he couldn’t be happier. Studying literature and even trying his hand at writing, he says, has made him reconnect with the story of humanity.

It was about here that I received an urgent message on my phone—Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had just died. Upon hearing this, Mark expressed his awe at Kissinger’s longevity, comparing him unfavorably to John F. Kennedy and lamenting that “they always take the good ones”—before quickly clarifying that such a statement wasn’t an endorsement of the late President or his foreign policy. What he meant by this self-contradiction remains a mystery.

Mark explores a variety of genres in his writing. Early on, he tried his hand at poetry—but not content to rest on his poetic laurels, Mark has since branched into exploring narrative in unconventional ways—including through video games. For his class last semester “Sherlock in the Multiverse,” Mark worked on writing the story for a detective video game of his own design, a process that had brought with it many of its own challenges. While poetry is an act of pure expression, creating a narrative requires you to write about a world beyond yourself. “It's not just your own experience you write about, but those of the characters too. You create a world in your writing much larger than yourself,” Mark reflects.

Thankfully, Mark has a couple of narrative guides to look to in his two favorite books, The Odyssey and American Psycho. In Homer’s Odyssey, Mark finds an outlet for his love for fantasy and surrealism, and it excites him to be able to see in the stories of ancient peoples some of the same fears and anxieties that we deal with today. American Psycho, on the other hand, serves as a more contemporary guide to the pre–professional zeitgeist at Penn itself. Reflecting on his time in business, he tells me very seriously that the business card scene from the movie is almost identical to his real life experiences with finance resumes, which are often “just one of three templates taken off of Wall Street Oasis.”

Despite his excellence across the disciplines, Mark still strives to better himself. With a laugh, he told me in earnest that “I want to get better at finishing.” The keyword for him is discipline. Like many passionate people, Mark starts a lot of projects, but finishes much fewer, a trend he hopes to correct in the future. One place where he has found such discipline is in his athletics. Having a strict practice schedule means he constantly works to build himself up—more than anything, he loves seeing the work he puts in pay off. When asked how it felt to be the pinnacle of Greco–Roman masculinity, he just laughed and told me that he “likes getting stronger.”

Walking back to my dorm with the wind still biting at my extremities, I asked myself: What did I learn from this Renaissance man? I felt no closer to answering any of my questions about my life or my purpose. But perhaps that’s the point. When we focus too much on goals and ends, we lose sight of the grand journey of life and all that it offers us. But in opting for passion, Mark shows us that we don’t have to live for our future careers—all that matters is bettering ourselves and experiencing the now.