As students across Penn’s campus frantically scramble to fill out next year’s housing application, many find themselves shuddering at the thought of spending a year in the high rises while their friends enjoy lattes at the Gutmann coffee bar. These hardships, though, pale in comparison to the bleak reality of other city residents who find themselves unemployed, uninsured, and unhoused. The Mutter Museum’s new art exhibit, “Unhoused: Personal Stories and Public Health,” illuminates the complex biosocial underpinnings that drive the unhoused population and its persistence across Philly’s most densely populated regions.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 4,725 individuals experienced homelessness in 2023, a 5.25% increase from 2022. Although post-pandemic rates of homelessness in Philadelphia decreased, 2023 marked the greatest overall annual increase of homelessness that the city has seen within the last fifteen years. “Unhoused: Personal Stories and Public Health” reflects the pervasiveness of the unhoused experience across the world while exploring its categorization as a global health crisis.

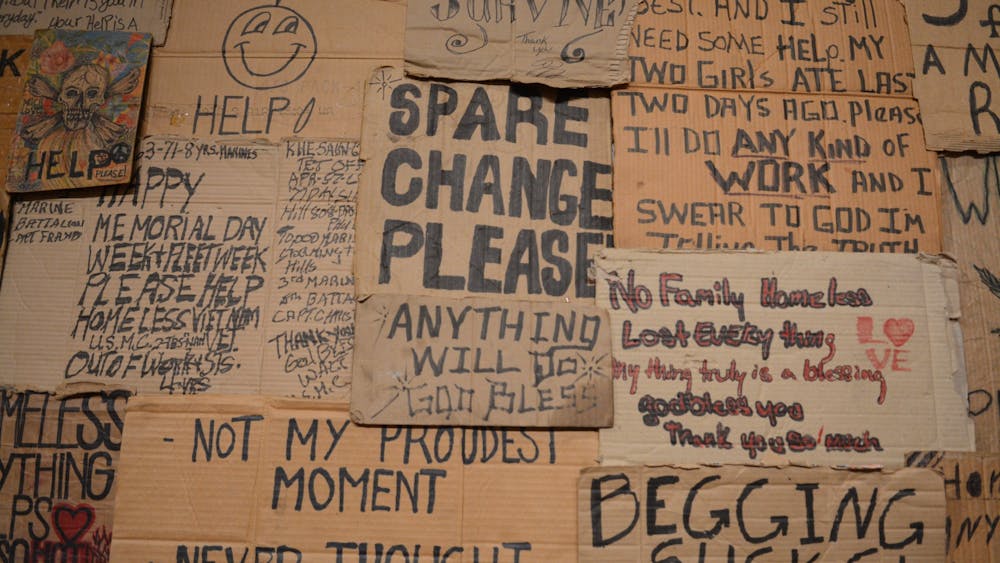

Created through collaboration between Public Health Chair of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia Rene Najera and Thomas Jefferson University College Fellow Rosie Frasso, the exhibit features artwork from photographer Leah den Bok and artist Willie Baronet. One half of the piece is composed of forty black and white photographs of unhoused men, women, and children from across the globe, while the other consists of more than eighty cardboard signs that Baronet bought from unhoused individuals over the course of the last thirty years.

Artwork displayed in the Mutter Museum's new exhibition, “Unhoused: Personal Stories and Public Health”.

Artwork displayed in the Mutter Museum's new exhibition, “Unhoused: Personal Stories and Public Health”.

The exhibit reflects Mutter Director Kate Quinn’s desire to shift the museum’s primary focus to health rather than death. With this exhibit, the museum aims to refocus the narrative surrounding being unhoused onto societal factors that have led to this global health crisis, rather than perpetuate a narrative rooted in individualized blame.

Beyond its educational component, the new exhibit reflects art’s potential to enact social change and galvanize broader societal discourse. Through its photographic representation of the emotional tumult that accompanies being unhoused, the exhibit encourages individuals to consider the unique stories underlying those who found themselves unhoused.

“In most exhibitions, I usually only use 5 to 10 photos, but for this exhibit I was able to use forty,” den Bok said in an interview with 34th Street. “I thought it was wonderful because I wanted to show more photographs and stories to accomplish my two goals for my project—humanizing people’s experience with homelessness and trying to share their stories.”

Inspired by her own mother’s experience with homelessness, den Bok hopes that the exhibit captures the untold stories of the unhoused while challenging preconceived notions of homelessness. By amplifying the voices of the unhoused, she believes that there is infinite potential to cultivate empathy and establish a foundation for meaningful change.

“My mother Sara was homeless as a child,” den Bok said. “She was living in Calcutta, India, and a police officer took pity on her because she had a deep wound on her face, and he knew that Mother Teresa dedicated her life to helping those experiencing homelessness. So, he brought her to Mother Teresa’s shelter where she was raised by Mother Teresa and the nuns until the age of 5 when she was adopted by a family in a small town in Ontario, Canada. Needless to say, if it wasn’t for Mother Teresa dedicating her life to those experiencing homelessness, I wouldn’t be alive today and my mother wouldn’t be alive today.”

Additionally, by placing the unhoused experience into the context of public health, the Mutter Museum hopes to shed light on a neglected facet of the issue and its persistence in contemporary society. Frasso aims to shift the negative connotations associated with homelessness through the amalgamation of art and science.

“The public health lens forces us to look at systemic structures that lead to housing insecurity – and it pushes us to respectfully consider each individual experience while considering the collective experiences that have led to growing issues – like housing insecurity,” Frasso said in an interview with Street. “We ask, why are people left to live on our streets? What upstream measures could we take to prevent this and, at the same time, what can and do we need to do now to solve the issue? Are there harm reduction strategies that would lessen the risk of poor outcomes for those who are unhoused?”

The exhibit depicts the dehumanization that unhoused people are often forced to endure. In particular, it sheds light on the complexities of the unhoused crisis, a subject which many housed people remain ignorant of.

“We hope, Willie Baronet, Leah den Bok, and I, that our collaboration leads people to consider how they may be contributing to the dehumanization of people living on the street, in shelters, or without a consistent safe, warm place to rest,” Frasso said. “We hope the exhibit gives people space and time to reflect on the crisis at hand. It is far too easy to live your life and not "see" those that we pass by. Also, the exhibit gives people space to share their own experiences of housing insecurity and what home really means to them.”

Aiming to foster a community of understanding and empathy, the exhibit’s focus on public health allows the public to gain a better grasp on the social factors contributing to the number of those unhoused in Philadelphia and to unlearn pernicious stereotypes that continue to unfairly disparage those who find themselves unhoused.

“We wanted to humanize people who are unhoused [in hopes that their stories would resonate with those who came to visit the exhibit] and become proactive in wanting to address housing insecurity,” Najera said in an interview with Street. “We hope that when people now encounter somebody who is unhoused, they may see them as one of their neighbors and one of their community members instead of somebody to stay away from or somebody to avoid.”

The Mutter Museum will continue its commitment to mitigating the prevalence of homelessness in Philadelphia by partnering with local non profit organizations such as Project HOME. Based in the heart of Philly, the service initiative has worked for 35 years to combat homelessness in the city by providing supportive, affordable, and permanent housing for unhoused individuals and families.

Writing about the impact Project HOME has had on her experience with homelessness, Project HOME resident Bonita wrote in a statement published to the organization’s website that “Project HOME not only provided me with a place to live, but gave me the stability to achieve my goals and care for others. To put others before ourselves is such a beautiful thing. I am so grateful for the commitment of everyone who helped make my dreams come true. There really is no place like this home.”

Through the Mutter Museum’s new exhibit, students have the opportunity to realize that behind every statistic surrounding homelessness lies a personal narrative, a life plagued by adversity, and a story untold. The museum proves that it is important to humanize the unhoused crisis and recognize the lived realities of those who are unhoused, and to regard them with compassion rather than apathy.

Humanizing the unhoused experience means that society must begin to acknowledge the inherent worth of every individual, regardless of their socioeconomic status, and recognize that being unhoused is not the product of personal deficiency, but instead a direct result of institutional biases, systemic injustices, and mental health toils. By humanizing the unhoused experience, perhaps this exhibit can help to cultivate a society filled with compassion rather than contempt.