Lauded as a pinnacle of American history, Philadelphia is known for its rich, colonial roots. From Elfreth’s Alley to Independence Hall, Philadelphia is replete with historical sites and districts that have continued to attract tourists from across the globe.

However, behind the allure of the Liberty Bell and Betsy Ross House, there lies a more sinister history of racial enslavement and oppression that is inextricably embedded within Philadelphia's historical monuments. Finding itself at the forefront of modern debates over the preservation of controversial landmarks, the Montgomery County Prison symbolizes a new era in which individuals across the nation are beginning to reevaluate historical sites in relation to their perpetuation of racist ideals and generational trauma.

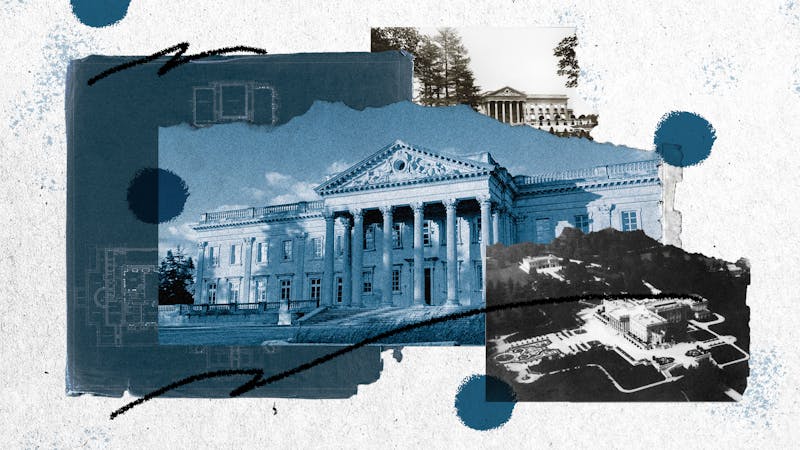

Constructed in 1854 in Norristown, the Montgomery County Prison was closed in 1987 and has been vacant for over three decades. Plagued by its contentious history of racial discrimination and disproportionate imprisonment of Black individuals, the prison has played a critical role in perpetuating criminal injustice in the county and inflicting emotional trauma on marginalized communities.

On Oct. 12, residents of Montgomery County gathered at the Norristown forum to share their perspectives on the prison’s historical significance as well as its potential to become an institution that promotes local penal reform. While some individuals posited that the demolition would be an injustice to the building’s remarkable architectural antiquity, others propagated that it served as a relic of the county’s racist past.

If the City Council moves forward with its plans to tear down the monument, they would need to invest $1.1 million in its demolition, yet many of the county’s city council members view the price as a small detriment to the plan’s otherwise overwhelming benefits. A staunch advocate against its preservation, Kenneth E. Lawrence, the chairperson and first Black member of the Montgomery County Commission, has been one of the most outspoken critics of the prison, claiming that its costly preservation only served to reinforce celebrating a criminal justice system that disproportionately targeted minorities.

Although Norristown’s commissioner, Jamila Winder, and the borough council president, Thomas Lepera, have echoed Lawrence’s calls for demolition, a significant quantity of Norristown residents remain committed to its preservation.

An adamant advocate for the prison’s preservation, Penn Associate Professor in the Weitzman School of Design Aaron Wunsch believes that the prison’s contentious past should not obscure its potential for enacting future reform. Delineating the architectural and historical value of the prison to Philadelphia’s history, he posits that the prison’s destruction would be a disservice to Montgomery County’s residents who consider the institution a cultural landmark.

Wunsch pointed out that the building was designed by Napoleon LeBrun, the influential Philadelphia–based architect also responsible for St. Peter’s Cathedral and the Philadelphia Academy of Music.

“It is the risk of losing the most iconic building of the 19th century,” Wunsch said. “The building is well built, structurally solid, and the kind of building that small municipalities surrounding Philadelphia can redactively use.”

In response to the Philadelphia Inquirer’s recent coverage of the event, Wunsch submitted a letter to the editor that presented in greater detail the reasoning underlying his opposition to the building’s destruction and his opinion on why the act is neither “moral” nor “practical.” Pointing out the success others have found with converting former prisons into centers geared towards justice reform, he cites Boston’s Charles Street Jail, Massachusetts Lowell Jail, and Philadelphia’s notorious Eastern State Penitentiary as prime examples of successful institutional penal reform.

He contests Lawrence’s moral argument against the prison’s precarious past, countering that “buildings and statues are radically different things and conflating them adds one more specious argument to those outlined here."

Wunsch further adds: “Modern prisons bear more powerful witness to mass incarceration than anything that the 19th century produced,” he says. “Historic buildings by contrast offer an opportunity to interpret the roots of such pathologies.”

Comparatively, Program Director of the Goldring Reentry Initiative Mary Archer believes that the prison has the capacity to translate its past transgressions into educational opportunities; by converting the prison into a space dedicated to penal reform, the public is able to delve deeper into the historical development of Philadelphia’s current criminal justice system.

“I think in a way it could serve to shift the community’s identity and shed light on the evolution of mass incarceration, our justice system as a whole, and national reform efforts,” Archer says. “Destroying it is not going to erase the past or do anything other than shut down any conversations that could potentially be had.”

Instead of attempting to expunge their previous misdeeds, Archer proposes that the prison leverages its unique, first hand insight into the inequities of the criminal justice system to enact civic discourse around persisting social issues. In the Goldring Reentry Initiative, Archer strives to uplift released prisoners and aid their rehabilitation back into society. By focusing on their housing, employment, mental and physical health, and education, the GRI embodies the power of restorative rather than punitive justice.

“The GRI takes our clients to the Eastern State Penitentiary every year,” Archer says. “It gives our clients a chance to learn about the past of the Eastern State and share their own experiences; it creates a wonderful learning opportunity.”

Echoing Wunsch’s and Archer’s sentiment in favor of the building’s preservation, other attendants of the Norristown Forum, such as Paul Steinke, the executive director of the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, Todd Poole, founder of 4Ward Planning, and local architect, Douglas Seiler, hope to see the city council members acknowledge the legitimacy of potential redevelopment projects as debates over the building’s demolition persist.

In response to the city council members’ adamancy for the institution’s eradication, Steinke established his own community organization that campaigned for the prison’s preservation by printing and distributing T-shirts and posters. On Aug. 3, the campaign’s efforts culminated when the organization published a Change.org petition that currently boasts 2,182 signatures in support of the prison’s preservation.

Within the petition, citizens postulate that the jail is a rare emblem of the “Golden Age of Architecture” and a critical component of the Norristown skyline. Rather than demolish a structurally sound building that has become a central part of the county, residents alternatively suggest the city provides the building with the financial means it requires for renovation. With the city council set to hold its next meeting on Nov. 8, residents’ burgeoning opposition to the destruction could hinder future plans to move forward with the institution’s demolition.

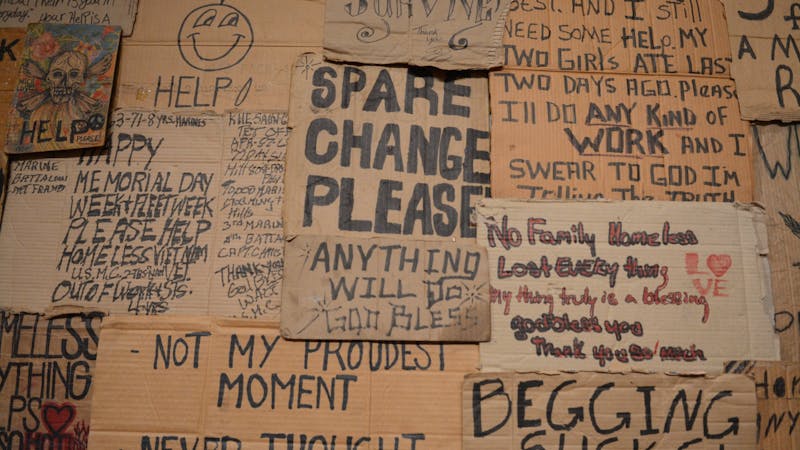

As tensions continue to mount between residents and city officials, the persistent controversy surrounding the prison reflects the broader national debate that has emerged in recent decades, prompting states to reevaluate the preservation of racist monuments. While the past year has seen a multitude of statues dedicated to Confederate soldiers be torn down across the country, there are no finite guidelines on how to approach institutions with more covert racial undertones.

Calls for the removal of racist monuments in the United States have only been exacerbated by recent protests against systemic racism and recurring incidents of police brutality. Frustrated by the pervasion of racial disparities across all facets of contemporary society, a vast array of citizens have begun to strengthen calls for certain monuments’ removal.

Even though it is naïve to believe that the demolition of certain monuments will miraculously heal the communities whose oppression it represented, it is imperative that government officials and state leaders begin to listen to the voices of those whose existence continues to be plagued by the prevalence of systemic racism in modern society. Exemplified in the conflict surrounding the Montgomery County Prison, there are a myriad of ways to approach criminal justice reform that diverge from simply tearing down controversial monuments. By reshaping historical narratives and working to reform the modern social justice system, the fate of the Montgomery County Prison has the potential to spark widespread institutional change.

“The county has not thoroughly explored options to save the building. There has not been an analysis on redevelopment opportunities or a consideration of where this landmark for historical injustice can contribute positively to the issue,” Archer said.

By converting the prison into a center geared toward reform, she believes the prison can help “show where we are today and what incarceration looks like. It starts a conversation around reform efforts and, even globally, where the US is compared to other nations. It’s not a fun little tourist attraction, it’s an opportunity to learn.”