You can tell how admired someone's work is by how their academic peers celebrate their triumphs. At his winter book launch, it was clear that André Dombrowski is certainly well-recognized by fellow Art History scholars. After History of Art Department's celebration of Professor André Dombrowski's new book Monet’s Minutes: Impressionism and the Industrialization of Time, I sat down with the author in his out–of–a–movie Jaffe Building office to talk more about his process.

At the event, Dombrowski’s fellow art historians poked fun at Dombrowski’s 11-year journey to complete this book. But after talking to him, it seems rather impressive that he’s been able to accomplish such a feat in that time frame while remaining an engaged professor and mentor on Penn's campus.

Dombrowski distinctly remembers when he came across the idea for Monet’s Minutes. After teaching Impressionism for over 15 years, he always took notice of the “immense time pressure in impressionist art.”

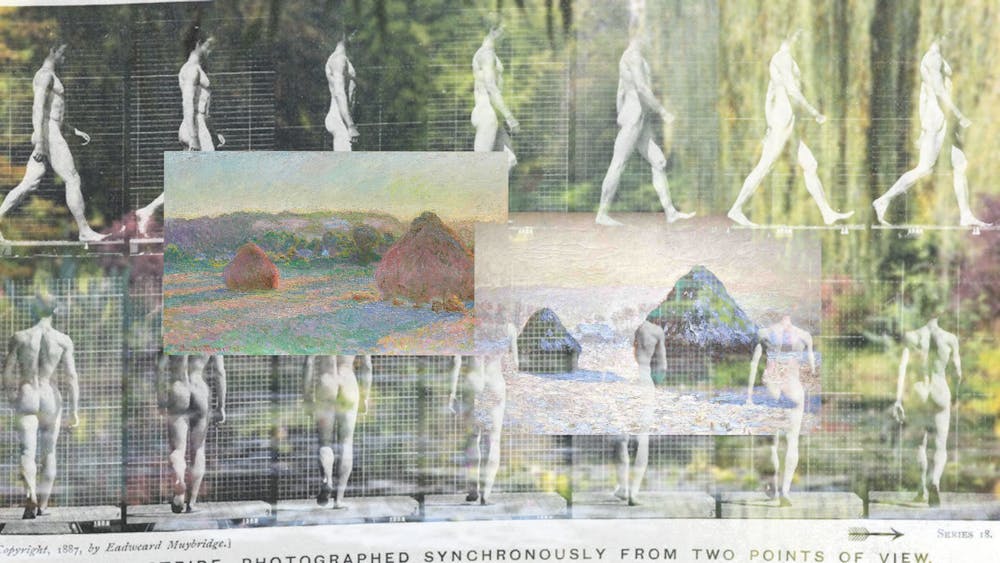

“Impressionism is all about instances, and moments and things have to happen quickly … like things are always fleeting,” Dombrowski says. When he began reading the work of Peter Galison, a historian of technology and science, the intersection of time and Impressionist art became abundantly clear. He recalls, “the late 19th century and the early 20th century was the time where Universal Time was invented, train schedules and the modern schedule of work created a whole mental habitus around time.” This time–focused mental habitus was the one Impressionist artists worked within, with the pressures of time prolifically apparent in their work.

But why did Dombrowski decide to center his extensive research on Claude Monet, out of the grand gaggle of accomplished artists? Dombrowski knew that Impressionism was to be the focus of his research, being that the Impressionist work was the first to show a “literal representation of time in the brushwork and hectic figurations.” Monet emerged as the emblematic impressionist, from the fractures of his painting to the themes he chose which were described as “quick ripples on water, all these sorts of ephemeral culture gestures.”

As an art historian, Dombrowski explains that he wants his artists to put a fist up against oppressive structures—like the invention of time to make the industry's Imperial structure and Imperial exploitation smoother and easier. Monet, he explains, is not that artist. Rather, he resists the imposition of time through his stylistic medium. In his work, Monet provides a sort of counter–temporality. The instant he puts on the canvas is essentially escaping the industrial time system. Dombrowski elucidates, “Monet is devising something that is of the system but not perfectly assimilable to the system.”

Once the connection between Monet and the invention of time took flight, the need for immense and original research was pressing. Dombrowski recalls constantly revising as new discoveries were made near and far. A living master of Impressionist art history, he visited the National Watch & Clock Museum in Pennsylvania and other museums centered on time in Eastern France and Switzerland to learn about the history of clockmaking and timekeeping. He recalls the euphoric moments when this history and its dates met perfectly with some of the crucial dates in Monet’s career. He explains, among other wild matchups, that in the mid–1890s when French time got assimilated within the new Universal Time and global time structure, Monet painted his Mornings on the Seine series. In this series, Monet is creating a sequence about a particular natural time, as that concept is being constructed, as it is permeating the life of society.

The wrestling between Monet and the imposition of Universal Time can widen our understanding of all art immensely. Dombrowski talks about how art is often identified with one specific maker and one artistic genius. Still, this way of thinking acknowledges “how it sits in opposition to but also in deep conversation with the kind of mentally intrusive kind of political, ideological, technological structures that modernity has invented,” he notes.

Dombrowski appreciates the freedom the Penn Department of the History of Art has allowed him to mold his upper–level courses as a vehicle for his research. Every other year, he teaches a lecture on Impressionism and shares that having students read and discuss his research shapes some of the book's content.

Monet’s Minutes: Impressionism and the Industrialization of Time adds a nuanced, scientific view to the conversation of Impressionism. Monet paints the real; he stands in the center of a train station and paints what he sees. By doing so, he allows that fleeting moment to escape the system, making its time indefinite, as it exists forever on the canvas. Like Monet’s work, Dombrowski’s work will surely become an indispensable, foundational part of the study of Impressionism.