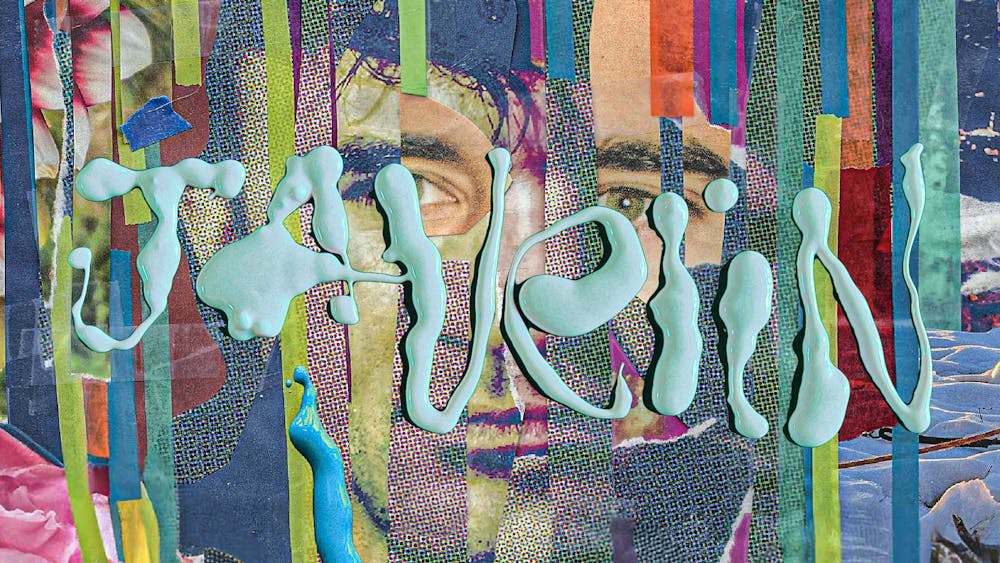

Three tracks into Sufjan Stevens’ newest album, Javelin, he asks one of the most simple and honest questions that perhaps anybody can ask: “Will anybody ever love me? For good reasons, without grievance, not for sport?” He isn’t looking for forever, or for massive promises. He just wants someone to be able to “pledge allegiance to my burning heart.” The fittingly titled, “Will Anybody Ever Love Me?” may be one of the best songs of Stevens’ long and varied career.

Each track on Javelin, Stevens’ tenth studio album, begins quietly. Acoustic soundscapes and philosophical lyrics bring to mind his much beloved album Carrie and Lowell and some of the softer moments on Illinois—the album that put him on the map as an indie songwriter. But these hushed beginnings pull away from his previous sound; they build into walls of shimmering, celestial music. This is a deeply spiritual album, concerned with love and loss, faith and worship. For Stevens, these ideas are inextricable.

In Stevens’ oeuvre, love is a religious experience. He’s written poignantly of his faith before, and this appears again on Javelin. On “Everything That Rises,” he wants Jesus to “come around before I go insane.” But these visions of love are also a twisted push–and–pull, where the emotional contradictions of loving someone and being with them can’t always coexist.

Take the opener, “Goodbye Evergreen,” which begins with careful, finger–picked melodies that suddenly explode into epic vocal harmonies and immense fractured beats, as if the arrangement is trying to physically expand. These dramatic shifts in mood and musicality flow throughout the album, but the peak of Javelin’s emotional contradictions comes in the eight–minute titanic, “Shit Talk,” a song about a relationship that’s run its course, but won’t—or can’t—end. The refrain, “I will always love you / But I cannot live with you,” rises from a glittering guitar arrangement into a lush orchestral and choral wave, which finally gives way to a lingering coda. These shifts could feel out of place in the hands of a lesser artist, but instead they feel like the natural emotional shifts of a couple in immense pain.

Javelin isn’t an album that can be separated from the circumstances of the artist’s personal life. It was made under deeply harrowing experiences, the agony of which bursts in and out of the album. Stevens was diagnosed this year with Guillain–Barré syndrome, a rare autoimmune disorder that causes a loss of mobility and feeling in the limbs, and recently lost his partner to chronic illness as well, a heartbreaking revelation that only deepens the emotional experience of listening to Javelin.

In a brief letter to his fans on his Tumblr, Stevens recently wrote, “I’ve often been the poster child of pain, loss, and loneliness. But this past month has renewed my hope in humanity.” He was referring to his ongoing treatment for the aforementioned Guillain–Barré syndrome, but his message could also be a thesis statement for this new album. Javelin finds Stevens looking inward so that he can get to the other side—so that he can get to recovery.

Stevens has probed the depths of grief before, most famously on the aforementioned Carrie & Lowell, which was about the death of his mother. Yet, where Carrie & Lowell found the sublime in sparse production with just a few bright spots, Javelin is full of turns of musical phrase that lift the songs up, making them lusher, brighter, and larger. With the exception of “Shit Talk,” which dissolves into a calm ending that lingers like a fine mist after the emotional thunderstorm, each song rises and builds to a hopeful, cathartic doorway into the next. Each point of introspection is weighed against the moment of catharsis, of looking outward. Stevens’ intimate vocals give way to choruses and layered harmonies that evoke freedom both in pain, and from pain.

The final track on Javelin, a cover of Neil Young’s “There’s a World,” is a doorway into new headspace and a new life beyond grief and pain. Where Young's original 1972 was smothered by melodramatic production, Stevens lets the delicate melodies breathe. Gone are the weighty soundscapes and the overwhelming atmosphere. He also adds the “I” pronoun to the song, in a subtle edit that tells you that Stevens himself is looking for the light on the other side. It’s the only track on the album that flows into one easy pace, that opens up without any buildup, illustrating just the simple, evocative hope that there are coming “good things in the air for you and me.”