The day is almost here. An explosion of Penn pride is only a breath away. Homecoming, an annual tradition dating back more than a century, welcomes students and alumni alike to celebrate school spirit and enjoy an all–American game of football. This Saturday is the day for Penn kids to rally. To flood the streets with blue and red. To darty–hop all the way down Locust to Franklin Field dressed in their finest bookstore merch. To cheer on our fellow Quakers against Cornell and the Big Red Bear. And, of course, to raise a toast to our dear old Penn.

But what’s merely a yearly tradition for us is the weekly routine of many other college students. Big Ten schools like Ohio State, UMich, and Purdue appear to have an overabundance of school pride, dedicating most Saturdays to cheering on their football teams, adorned in school merch and sporting painted faces. At these universities, tail–gating is practically another class. To put it bluntly, they make our festivities look pitiful.

It’s no secret there’s a lukewarm spirit for sports at Penn. Bleachers remain half–empty and even a fan favorite like football struggles to fill a fraction of Franklin Field’s over 52,500 seats. For the average Penn student, athletic events never make it into their intricately woven Google Calendars. We’re distinctly disinterested in sports, a paradoxical situation since athletics is what deems us an “Ivy League” school.

An official Ivy League was first proposed in 1936 in an editorial piece “Now Is the Time,” which appeared in all but one of the Ivy’s respective newspapers, including our very own Daily Pennsylvanian. The article pushed for the creation of an athletic league among the seven universities (Brown University not yet included), on the basis of our “common interests” and “similar general standards.” Although the Ivy League had been an informal association for years prior, the editorial argued that an official standing would be much more effective and allow the universities to “assume leadership for the preservation of ideals of intercollegiate athletics.” A bit pretentious in its assumption of Ivy League superiority, the proposal would fail in 1936, but the discussion would continue.

The Ivy League was made official in 1946, then intended just for football, but later extended to all collegiate sports in 1954. The eight prestigious universities agreed to prohibit athletic–based scholarships in favor of need–based financial aid. Their goal was to promote student–athletes being students first and athletes second, as a response to professional sports teams recruiting collegiate athletes.

Penn’s reputation was thus cemented as academic above athletic, but this executive deemphasis of sports doesn’t entirely account for the origin of our lackluster fan culture.

In its arguments, the 1936 editorial provides an interesting perspective on fans a century ago: “There can be no doubt that the formation of the Ivy League as an official entity would at once create a wholesome enthusiasm among the members of the institutions involved which is usually lacking now except during championship seasons.” So it was a problem then, and it’s still a problem now. The hope of manufactured rivalry between elite universities appears to have had very little effect on students’ game attendance.

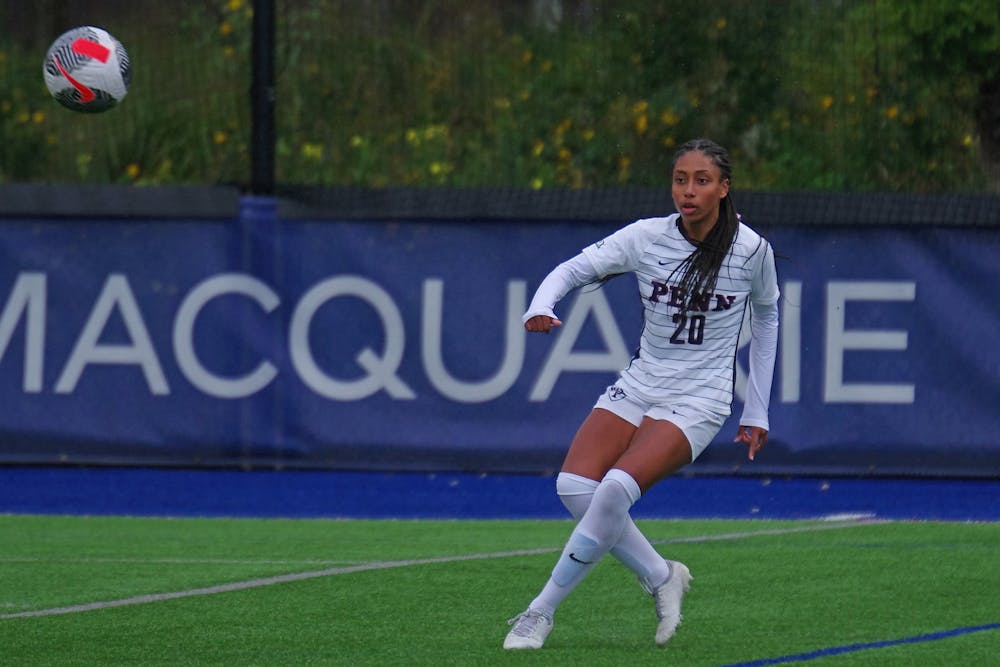

The editorial asserts that, in creating this league, “anti–climactic games would be eliminated,” but that has yet to hold true. As little as school rivalry motivates the student populus, so does a team performing particularly well. Soccer player Ginger Fontenot (C ‘24) weighs in on whether team performance or a particularly good season affects turnout. “There are games that we’ve played that have been really tight,” she says. “We’ve only ever lost by one goal the past two years. I think the intensity has been the same throughout … and the volume of the fan base has been the same.”

Ginger’s been playing soccer for years, taking an impressive highschool career to the college level. And over the last three seasons, she’s started almost every game, proving herself a valuable member of the team. Ginger just finished out her senior season with a 2–1 win against Cornell. She speaks fondly of her time as a student–athlete, despite having to balance rigorous academics and a demanding practice schedule.

Photo Courtesy of Ginger Fontenot

In terms of the fan culture surrounding the women’s soccer team, it’s typically only friends and family who attend games. “I don’t often see people in my classes coming by Penn Park. The academic community isn’t necessarily as interested in our games as those with connections to the team would be,” she says.

Ginger wasn’t exactly surprised by the indifference at Penn. The venn diagram of her fans and her social circle has always been just that—one circle. But that doesn’t mean she wouldn’t mind stronger audience support. “Of course I wish there was a larger fan culture on campus because it just makes the game more exciting,” she says. “It gets gritty and it gets intense and that environment is always really fun to play in.”

Even if Ginger doesn’t feel much support from the academic community, she’s managed to find it in other ways. Internally, the soccer team has created a tight–knit group that doesn’t always need onlookers to cheer them on. “Personally, I think one thing we learned this season is to create our own vibe.”

Support from other student–athletes has also been integral to creating that energetic vibe. Ginger finds that the big groups cheering her on are typically other sports teams. “We share this lifestyle, so we naturally gravitate towards those people,” she says.

That support goes both ways for Ginger—she always makes an effort to cheer on the other teams from the bleachers. Rooting for her friends on the track team, attending football games—especially when they’re on Friday nights—and supporting her “brothers in arms” on the soccer field, Ginger is as competitive on the field as she is in the stands.

Squash player Shaam Gambhir (W ‘25) similarly talks of a kinship with other Penn athletes on the basis of being just that: athletes representing the same school. “If I’m watching lacrosse, like Princeton versus Penn, obviously I’m like ‘Oh, well, fuck Princeton,’” he says.

However, Shaam finds the connection to be even deeper within his own team. “I’ve never been surrounded by so much support,” he says. In his transition to collegiate squash, Shaam found that a once individualistic sport became heavily team–focused: “I’m from the U.S. and I was one of the best in the country. All of a sudden, [I’m] find[ing] myself on a team full of the other best people from wherever they came from.” He speaks to the difficulty of that transition and the ultimate realization that “it’s not my job to look out for myself, but actually look out for the team.”

Photo Courtesy of Shaam Gambhir

That team support extends beyond current players. Shaam emphasizes the extensive alumni network and connections head coach Gilly Lane and assistant coach Stuart Crawford have managed to build, creating some semblance of a fan base for the current players. The legacy they’ve left behind has allowed the team to grow and recruit top players, and Shaam often finds alumni attending games when they get the chance.

He admits that the fan support he’s experienced is perhaps unique to the squash team. Shaam often finds a mix of fans at their matches, from parents to frat brothers. “Things get exciting,” he says, "it’s not even that way on the pro tour.”

The strength of the squash community even follows the team outside of Philadelphia. “We have lots of parents and definitely some students that travel to see these games—places like Harvard. That’s not a close drive,” he says.

Shaam can’t quite put a finger on why Penn squash draws such a big crowd. He suspects the collective aspect of a typically individual sport is what keeps alumni coming back, but ultimately leaves it up in the air.

While there’s certainly a lack of sport fan culture among students, there’s also an acute awareness of that fact. It’s nearly a campus–wide inside joke. Ask most undergrads about the game day attendance, and they’re quick to tell you there’s little—or none, for the especially cynical. Our awareness, however, is not indicative of complete apathy. Many student non–athletes are also searching for a strong Penn sports fan base.

In a Daily Pennsylvanian article published earlier this year titled “Will attending Penn sports ever be cool?,” Sports editor Walker Carnathan (C ‘26) reiterates the sentiment expressed almost a century ago in “Now is the Time.” He’s quick to diagnose the issue, writing, “At other schools, sports are cool. At Penn, they’re not.” Walker doesn’t let the excuses of poor performance or lack of tradition fly; rather, he believes a total revitalization of the social scene surrounding sports is needed.

The student body’s ability to rally around other causes can be translated to Penn sports. He places a direct call to action on the shoulders of students. “Penn’s student–athletes have done their part. Nearly every Quaker team is competitive within the Ivy League … Now, the burden falls on campus culture to give them the recognition they deserve.” Though this hope has yet to be realized, there are efforts being made amongst students.

For the past two semesters, president of the 2024 class board Omotoyosi Abu (W, E ‘24) has been sending out weekly or biweekly emails announcing upcoming sporting events. An avid supporter of Penn athletics, Omotoyosi finds the crowds at games to be “vibrant, active, and engaged,” but explains that there’s typically little presence. He hopes to expand on this untapped energy, saying “There are a lot of times where things will be really fun, but there weren’t many students in attendance.” With the support of the rest of the board, he’s been using their various sources of outreach to spread the word.

Though he couldn’t speak on specific statistics, Omotoyosi is optimistic that informing students is the best way to get them to show up. At the very least, he figures, it couldn’t hurt. “Let’s just get more people to be aware,” he says, “and then hopefully, they’ll choose to support our athletics.” He has found, at least, that his initiative is beginning to spread to the younger class boards. Omotoyosi’s seen other class presidents including sports previews, even if they’re not dedicating emails specifically to the topic. He especially notes 2027 class board president—and Street Style beat—Stephen Li’s (W ‘27) enthusiasm at the project and interest in incorporating athletics.

Furthermore, a new club is dedicated to increasing both energy and attendance at sporting events. The QuakeZone hopes to encourage students to not only attend games, but take active participation in watching them. They’re offering external incentives, like exclusive limited merch, to those who attend games. In honor of Halloweekend, they hosted a costume contest for the Penn versus Brown game last Friday.

With two committees, Quake–makers and Quake–shakers, the club is working both internally and externally to create a strong, enthusiastic community of fans. Socials, parties, meet–and–greets, student section activities, and a strong connection between students are all goals. The QuakeZone is new, and still getting its bearing, but its effect will be felt at future athletic events.

It may seem that our lack of sport support is written into the history books. The stereotypical Penn student is too busy with midterms, club meetings, and Greek life to bother walking down to the Palestra or Franklin Field for an evening. Still, Homecoming proves an important social event for the University, showing students are capable of serious school spirit, even if it’s only once a year.

Penn has a deep history with collegiate athletics and an already well–established student–athlete community. We might not have Hail to Penn or Roll Quakers, but we do have our literal and metaphorical toast to dear old Penn and all the makings for a ride or die for the red and blue.