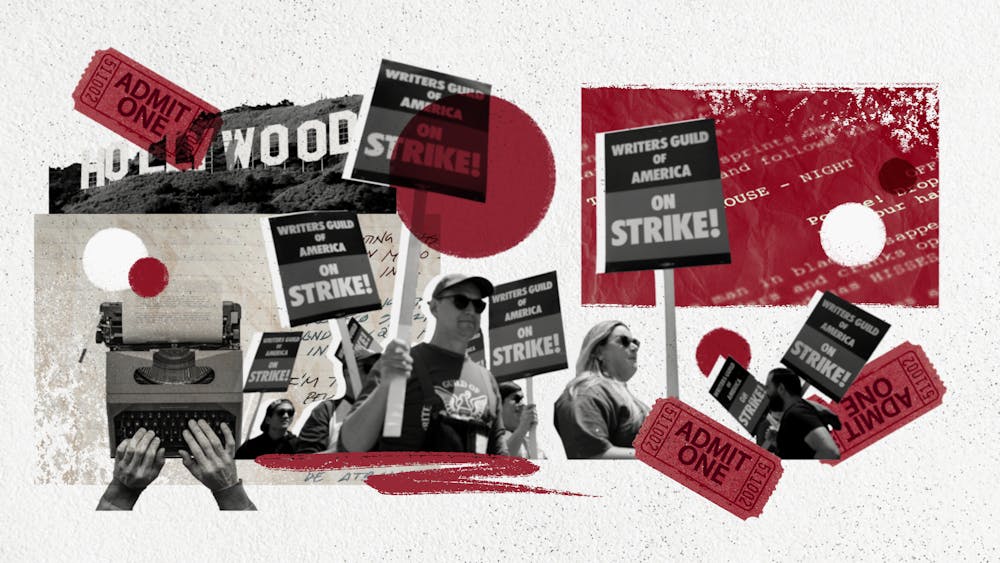

On Monday, Oct. 9, after nearly five months of being on strike, 99% of the membership of the Writers Guild of America voted to ratify the contract that the WGA negotiating team had reached with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. With gains made for a restructuring of the residuals model in the age of streaming, protection from AI, and assurances about the minimum amount of work a writer will get for a certain project, the deal is nothing less than historic.

As of the time of writing, WGA’s sister union, the Screen Actors Guild–American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, remains on strike, and that strike likely won’t get resolved for a while, considering how negotiations have fallen apart. This means that (with the exception of the projects that aren’t considered struck) most of film and television production is still halted. A notable exception is talk shows and late night television, which returned only days after the negotiating committee agreed to a contract, bringing talk show hosts and SNL back on the air.

However, one talk show, "The Drew Barrymore Show," did not immediately come back. Just two weeks before an agreement was reached, Barrymore announced that her show would be returning while the WGA was still on strike. Though technically allowed, as "The Drew Barrymore Show" was under a different contract than the one the WGA was striking against, the return would still have been considered crossing the picket line, because even a seemingly non–scripted show contains many pre-written parts. Though Barrymore retracted her decision a few days later, her writers refused to come back to work even after other talk shows got back on the air. At the time of writing, the show has made a delayed return — albeit without three head writers.

But talk shows returning to the air is far from the most important thing accomplished by this agreement. The new contract is a verifiable success for the WGA, as the guild won in an impactful way on a number of incredibly important issues. They have helpfully summarized their contract on their website.

Protection against AI taking over writers’ jobs was probably the most visible issue in the public eye during the strike. The fear among writers was that AI would be used to generate new material and writers could end up being reduced to glorified copy editors — not only would they not generate creative ideas, but they would also not receive compensation for conceiving and crafting new scripts. Additionally, the WGA wanted protection against their past work being used to train AI models. This fight is occurring on a lot of fronts, not just in this specific contract negotiation, with notable cases such as Sarah Silverman suing AI companies for using her work to train their models without her consent, which effectively allowed the models to plagiarize her work.

As the summary notes, the AMPTP barely even provided a counteroffer initially on the topic of AI, simply wanting to revisit the topic on a yearly basis. In the end, the writers ensured a slew of protections from AI, including that AI cannot function as a “writer” on a project and that companies cannot force writers to use AI software when working on a project. As for their work being used in the training of AI, the guild did not win complete protection, but they did reserve “the right to assert that exploitation of writers’ material to train AI is prohibited by MBA or other law,” according to the summary.

Writers also won an increase to their residuals base, meaning that they’ll make more money than before off reruns and streaming viewership. A new system was structured specifically for streaming, as the viewing landscape has changed drastically in a few short years. A major point during the 2007 WGA strike was a better system for residuals in the world of DVD and blossoming new media. This strike was a similar fight, with shows and movies being watched more and more on streaming sites rather than television sets or the big screen.

The agreement that the WGA and the studios came to provides the writers with a much better residuals system, including a 26% increase in the base for residuals for streaming feature films and bonuses for streaming television based on viewership data. Crucially, this change means that streaming platforms will have to be more transparent about their viewership data, something that helps not only the WGA but also television consumers in understanding exactly which shows are popular and how popular they are.

Another significant win for the WGA comes with protecting the amount of work a writer will get. With the rise of six to eight-episode seasons and the decline of 22-episode seasons, writers have been scrambling to find long-term job security in a way that wasn’t an issue before this new model rose to prominence. This contract both increased the minimum size of writing rooms, allowing for more writers to be employed, and guaranteed more long-term protection and employment, both pre- and post-greenlight of a show, for both writers and writer-producers.

Though the WGA strike is over, the SAG–AFTRA strike goes on. If you wish to support those affected by the strikes and can’t make it to a picket line, there are various funds to donate to, and even just showing support on social media can help. The writers won impressive and important protections, and ideally, the actors will, too.

This strike just goes to show the effectiveness of a united labor front and the necessity to adapt to a changing landscape. It’s also important to remember that, as executives throw around criticisms of the strike putting crew members out of work and impacting the greater Los Angeles economy, this contract was a deal the AMPTP could have offered months ago — it is because of the AMPTP that the strike had to go on for so long. Hopefully, when the WGA’s contract is up for renegotiation in three years, the studios won't make the same mistake.