Immediately, three beats of the song’s percussion draw you in. Friendly strings lead up into piano notes that hop back down before jumping into a funky beat. Sweet female vocals begin to sing of love and disco. From this description, “Plastic Love,” which was released in 1984, seems like your typical ’80s hit—perhaps an exemplary karaoke song, but nothing particularly groundbreaking.

But, unless you can speak Japanese, this isn’t your best choice for karaoke; you’ll only be able to sing the repeating English chorus at the last minute. “Plastic Love” is widely considered the quintessential example of a niche genre you may have never had the chance to encounter decades ago, but which is all over the internet now: Japan’s city pop.

City pop emerged in the 1970s, first loosely encompassing folk songs and kayōkyoku (literally translated as “pop tune”). Its rise was largely precipitated by Japan’s emerging economic power in the wake of World War II. During the war, Japan lost between 2.6 and 3.1 million lives and an estimated $56 billion. The outlook was bleak, but somehow in the next 40 years, its economy skyrocketed. This “Japanese Economic Miracle” occurred because Japan was able to start over. According to economists, it was free to experiment and innovate with new technology and investments. Japan’s exports also thrived with low prices and adaptability. U.S. aid and interventionism were at least partly responsible for the Japanese Economic Miracle in the years leading up to the Cold War. Scholars even argue that Japan’s comeback would not have been possible if not for its alliance with the United States.

In the 1980s, this economic boom led to a rise in consumer presence from younger generations. The vibrancy and excitement of city pop reflected the rapidly globalizing youth of Japan. There was money to spend, and they were eager to spend it. Just as those new to the workforce bought trendy clothing labels from Western designers, many city pop artists found their roots in experimentation with Western styles. Inspired not only by American pop, but also rock, jazz, and R&B, they created a sound that embraced change and positivity.

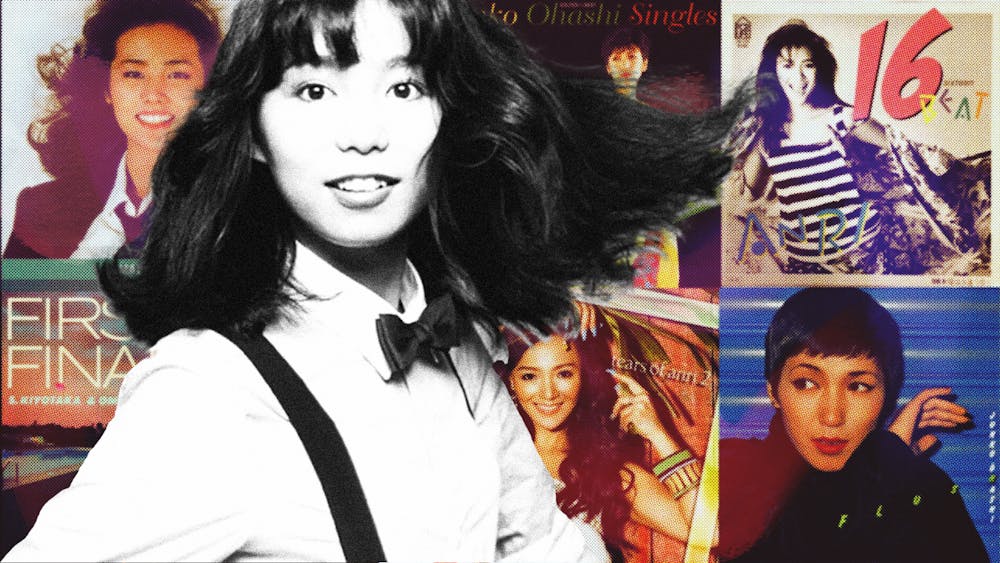

But as Japan’s economy declined at the turn of the millennium and other genres took its music scene by storm, city pop fizzled out. Though they had their moments in the sun, the likes of Junko Ohashi, Anri, and S. Kiyotaka & Omega Tribe seemed doomed to obscurity, their CDs and LPs shoved to the bottom of the pile. City pop, after all, had been a booming success in Japan, but its reach had failed to stretch far beyond the island. Perhaps it was for this reason that city pop’s renaissance was sparked not in its birthplace, but in the home of its original influences: the West.

The exact origins of city pop’s revival aren’t clear. Most likely, people dug through those piles of CDs and LPs, found proverbial musical gold, and shared it online. Many people who have discovered city pop in the past decade did so thanks to YouTube’s ever–inscrutable algorithm, and often through Mariya Takeuchi’s “Plastic Love.” In 2017, an anonymous user uploaded an eight minute version of the song to the platform. The video, which is now unavailable, boasted more than 55 million views as of early 2021. It was my own introduction to city pop. At the time, the song was absent from streaming platforms like Spotify, so the only way to relisten was to pull up that page. This inevitably led to further recommendations, and a rabbit hole of city pop content.

In addition to songs and albums by other city pop artists, I and many others encountered colorful mashups by creative netizens and covers by up–and–coming artists like Fujii Kaze, whose own music went internationally viral in the summer of 2022. Perhaps the most successful in terms of sheer numbers is an English interpretation by singer Caitlin Myers, over 13 million views strong. She went on to publish a seven—song compilation of city pop renditions to Spotify. Now, Takeuchi and her classic hit have officially been added to streaming platforms, and a stylish music video was uploaded in November 2021 by Warner Music Japan, with whom Takeuchi signed back in 1998. It embraces nostalgic lighting and visualizes the unexpected melancholy of the lyrics.

Beneath the surface, “Plastic Love,” or, in its original Japanese, “プラスティック・ラブ,” holds a more tragic meaning than its lively tune would tell. Translated to English, the lyrics tell the story of a woman determined to protect herself from future hurt. “Never love me seriously,” she warns. “Love is just a game … The showy dresses and shoes decorating my closed heart / Are my lonely friends.” Perhaps the fast–paced glitz and glam of Tokyo’s ’80s weren’t quite as perfect as their shine would lead one to believe.

The success of city pop, too, is not all that it seems. That such a niche genre can and did gain such rapid popularity, far beyond its original reach, is astounding. Years after the YouTube algorithm began to drop city pop hits in users’ suggested video lists, a TikTok trend emerged where creators played songs like Miki Matsubara’s “Mayonaka No Door / Stay with Me” for their Japanese mothers. On Spotify, city pop themed playlists boast hours of music and hundreds of thousands of likes. Famous Western artists, too, are dipping into the waters of city pop through their own music. One 1983 bop, for example, might sound especially familiar: Canadian singer—songwriter The Weeknd conspicuously sampled the instrumental from Tomoko Aran’s “Midnight Pretenders” on “Out of Time,” a track from his 2022 album "Dawn FM." What is it that is especially attractive about this genre, here and now, in the 2020s?

City pop’s rise coincides with a general increase of interest in Japanese culture in the West. Between 2020 and 2022, for example, demand for anime content increased by 118%, alongside discussion that the television genre might finally be entering the global mainstream. (Those original listeners to city pop on YouTube know that bootlegged songs and playlists often feature looped gifs of aesthetic anime sequences and characters.)

Not coincidentally, the same internet ecosystem that has boosted city pop is facilitating this cultural exchange. A quick visit to TikTok, X (still colloquially called Twitter), or Reddit reveals entire communities with as many as 8.2 million members. Is there a commodification to the newfound popularity of “Plastic Love” and its compatriots? Some write that the genre’s comfortable ’80s conventions establish its familiarity, while the fact that lyrics are in Japanese “preserve an aura of exoticism and mystery, giving Western listeners room to project their desires.” Comment sections filled with fictional daydreams about driving with the windows down in Tokyo seem only to support this orientalist romanticization of a foreign country and time. But then again, city pop emerged because of and fed into its own era of hyper—commercialization and materialism, inspired at least in part by the West itself, both economically and musically.

So what are we to make of city pop? Though its resurgence prompts plenty of political and cultural questions, what cannot be in doubt is its position as proof of the internet’s power. Years after its initial rekindling online, city pop remains a favorite genre of many music lovers who would have never even heard of it otherwise. I, for one, hope that (for all their shortcomings) platforms like YouTube and TikTok continue to introduce us to vibrant relics of the past.

But as anonymous profiles and perplexing algorithms work even more into the musical conversation—and onto our own playlists—it’s worth asking why we listen to what we do. And if you can do that while dancing to the tune of a city pop classic like “Plastic Love,” all the better.