A few inches away from a dumpster in a parking lot sit half a dozen people, their legs hanging over a hole they’ve been digging for the last week. It’s a motley crew. An undergrad student works in sync with a Ph.D. who’s decked out in round glasses and a safari hat to clear away the dirt with brushes and spades. A professor helps an older woman get up after her legs fall asleep while digging in the pit. A mom and her 13–year–old son can hardly contain their excitement when they find a broken glass bottle.

The pit is around the size of a TV, shaded by a tarp tent, and sectioned off with string and stakes. A few feet away are even more sites. One is much deeper, a girl standing up to her waist in what was once a stone privy. Another towards the back of a parking lot sits right at the fender of a car. It’s slow work, but at any moment a discovery could be made. The groups dig carefully with brushes and spades, pulling out measuring tape to record the depth at exacting precision. Dirt is stored in industrial buckets that are laid upon a tall screen and shaken, dusk obscuring their faces until it all settles and a glass shard or bottle cap emerges from the debris.

Credit: Rachel Zhang

The word “archaeology” usually triggers our childhood obsessions with Ancient Egypt and Greece, maybe even Mohenjo Dara–Harappa if you really paid attention in world history. But as Penn archaeologists Megan Kassabaum and Sarah Linn have discovered, plenty of stories live right under our feet here in University City. After all, University City wasn’t always University City.

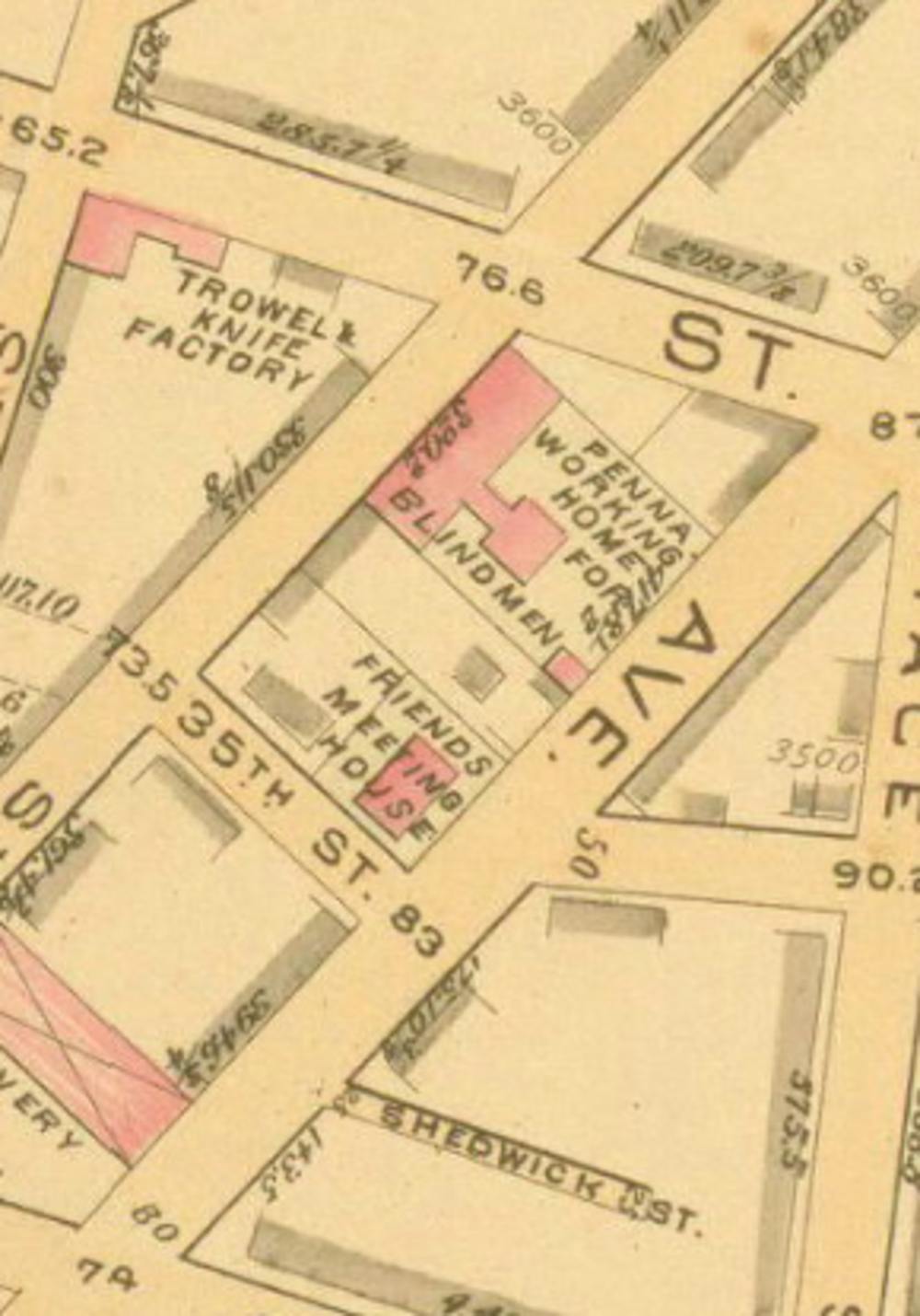

Black Bottom c. 1888|Image courtesy of Megan Kassabaum

One hundred years ago, if you visited anywhere between 32nd and 40th streets, you would’ve found yourself in a vibrant, residential community known as the Black Bottom, named for the fact it sat at the base of a hill. The origins of the Black Bottom can be traced back to the 1850s, long before Penn became an established presence in West Philadelphia. Over time, the neighborhood grew as migrants from the South settled during the Great Migration, establishing a flourishing Black community.

In the Black Bottom, neighbors were friends and friends were family. Front doors were left unlocked, kids would play in the street, and if someone couldn’t pay their rent, the block would throw a “rent party” as a way of fundraising. “It was a very tight–knit community. A very protective, tough, strong, fighting community that protected its own. It was poor people, middle class and working class people all combined,” remembers former Black Bottom resident and Penn professor Walter Palmer. “I used to love the block parties where they would block off the street in the evening and have music and dancing and eating and the children were allowed to stay up.”

However, beginning in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the expansion of the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University threatened this thriving ecosystem. The community was systematically dismantled. Developers began to move in, buying up buildings and allowing them to deteriorate. The city condemed the area as “blighted” and slated it for urban renewal, much to the benefit of Penn, which, through eminent domain, was able to buy the land for cents on the dollar.

The Black Bottom organized in resistance. “The spirit of a community is what has driven so many of us. We fought Penn between 1960 and 1970. Really, guerilla warfare, in the streets almost, using every technique and every skill we had to try to stop them,” says Palmer. He led many of the demonstrations, including laying down in front of bulldozers and sit–ins at College Hall. “But eventually the community was overwhelmed by it, by the bulldozers and the people who had sold out.”

Today, most people aren’t aware that the University sits on top of a historical community. Not too long ago, Linn was among them. “I actually didn't know there was this neighborhood that was replaced [by] these large buildings we now call University City,” she reflects.

In 2019, Linn and Kassabaum, an Anthropology professor at Penn, began discussing the concept of a local archaeological project situated in West Philly. “Most of the Penn Museum's projects are about Egypt or Turkey. We [not only] wanted to do something local to make archaeology more relevant, but also to democratize access to archaeology,” Kassabaum says.

Kassabaum points out that archaeology is a practice usually reserved for people who have access to training at an elite institution: “I think it's important for people to recognize that the stuff under our own feet is archaeologically and anthropologically interesting.”

Plenty of archaeology has been done in Philadelphia; however, most of the narratives tend to center Old City and the founding of America. But as Autumn Melby, a Ph.D. student on the dig, notes, “You don’t need to be in Old City to know that there’s history all around you.” The project was designed to be carried out in collaboration with the West Philly community, and through conversations between researchers and residents, the story of the Black Bottom came to light.

Credit: Rachel Zhang

By uncovering the toys kids played with, what people kept in their houses, and how the community spent their time, archaeology interprets the material history to tell the story of everyday life in the Black Bottom.

“We believe that there’s some value in putting artifacts on display that demonstrate what a vibrant community [the Black Bottom] was,” says Kassabaum. “Whether it's a button or a bottle cap that might have been used in a game, any of those sorts of things are the objects that allow us to give life and color back to a place that we know was vibrant.”

But urban archaeology poses unique challenges for archaeologists who have spent most of their careers digging in the remote mountains of Greece or the cornfields of Mississippi. University buildings were built over most of the Black Bottom, making it nearly impossible to access the stories hidden beneath. And yet, through conversations with local organizations like the Black Bottom Tribe and HopePHL—formerly known as the People’s Emergency Center—the perfect dig site emerged.

Right next to a trendy ramen spot, the Community Education Center seems out of place amidst Lancaster Street’s array of coffee shops and restaurants catered towards Drexel students. It’s a large brick building used for hosting community art classes and programming. While it’s gone through many iterations, it seems that the auspicious spot has always been centered around bringing people together.

Before the destruction of the Black Bottom, the spot was home to an integrated school for kids in the community, and even earlier, a Quaker Meeting House run by staunch abolitionists, serving as one of the last stops in the Underground Railroad. Homes occupied what is now the CEC parking lot, and since no new buildings have been built over the parking lot, it’s an ideal spot to trace personal and communal life in the Black Bottom. The dig is specifically looking at two wooden homes and a group of brick rowhouses behind what was the school. While the wooden homes were taken down in the ‘30s, the rest were demolished during the bulldozing of the Black Bottom. Researchers theorize that one of the houses may have been a boarding home that particularly catered to new migrants from the South. In conjunction with census records, the project can use the artifacts recovered to distill a story of what it meant to live in the Black Bottom.

The official excavation began this fall, subverting plenty of archaeology norms along the way. Urban archaeology, by definition, is caught in constant flux between a search for the past and the modernity of its surroundings. Researchers look to recover discarded items that might offer some insight into everyday life, or as Linn puts it: “trash.” While on site, a researcher with archaeology experience named Darnell who happened to stop by the site a few days ago and immediately joined in, demonstrates how to sort through a bucket of dirt for potential artifacts. Using a magnet, he pulls out a square–shaped nail caked with dirt, so small that it could fit on the tip of his pinky. The item doesn’t seem out of the ordinary—just a loose nail that by chance happened to be uncovered years after it was lost. But in the hands of an archaeologist, this nail, alongside the other artifacts, can offer insight into the presence of smiths in town, the materials and quality of houses, and even trade with outside communities.

Alongside undergraduate students in a fieldwork class and Penn–affiliated Ph.D. candidates, many of the people on site are volunteers from around West Philly excited to uncover the hidden treasures of the Black Bottom. Professional archaeologists train them to use various tools, delineate plots, and find archaeologically significant items. As one older volunteer proudly exclaims, “This is the closest I’ll get to Egypt!” But unlike any dig of Ancient Egypt, this woman can actually lay claim as part of the history she’s digging up. She grew up near the Black Bottom, visiting so often that she and her sister would refer to these trips as “going down the way.”

Credit: Rachel Zhang

Many people have their own stories to share about the Black Bottom. Some passersby are drawn in by the spectacle of the dig. Looking around the excavation some of the recovered items inspire their own memories of the Black Bottom long hidden in the recesses of memory

One such item is a flat bone button, around the size of a dime. When a former Black Bottom resident saw the button, it sparked a flurry of memories about a woman who used to dress up for church on Sunday in outfits covered in buttons and bows, aptly nicknamed "Buttons ‘n Bows". “For us, that felt like a magical moment because it was one tiny, somewhat insignificant artifact that inspired her to remember and tell us about this person,” says Kassabaum.

On the front gate of the dig site, the researchers strung up a timeline, that passersby could fill out with their own local knowledge. Some people have scrawled in the dates of demolitions while others record local birthdays and stores. Many people aren’t aware of the power of their stories, declaring they have nothing to add to any academic, only to offhandedly share an anecdote that adds to the growing narrative of the Black Bottom. One of Linn’s favorite encounters was with a man who, after denying any important “knowledge,” casually brought up the Christmas lights that once covered Lancaster Avenue in the winter, painting a picture of the joy and celebration in the community.

Credit: Rachel Zhang

As with any archaeological dig, things are still a mystery. One of Linn and Kassabaum’s favorite discoveries is a collection of slate pens found in a closed–off privy. The pens, though decades old, still work, and a piece of blackboard even showed up in the mix. Linn hypothesizes that students at the adjacent school building may have repurposed the old privy as a dumpster. The question of who used these items is answered. Were they students from the Black Bottom? What were they writing? And where did they grow up—are they still around walking in this community or have they long since been displaced?

The site has become both a space for collecting information and educating others. Many students from Drexel and Penn stop by, having never heard of the Black Bottom. The excavation allows people to understand the Black Bottom as more than a story of “what once was”—rather, a piece of a living history that is still part of University City’s legacy today. As Darnell puts it while uncovering a group of bricks overturned by a bulldozer that demolished a house, “You can see the violence in these bricks.”

The dig will last until around Thanksgiving, after which the items recovered will be processed and analyzed at a lab in the Penn Museum by a team of professors, students, and West Philly residents. What comes after this is still in the works. “We want that to be informed by the community,” Linn says.

Former Black Bottom residents are excited about the possibilities of this dig. But Palmer notes that, when it comes to the damage inflicted on displaced people and erased communities, awareness isn’t the same thing as an acknowledgment from the university.

The story of the Black Bottom offers necessary context for the “Penntrification” of today. The University City Townhomes, an affordable housing development at 40th Street that was part of a citywide struggle for preservation, was slated for destruction in July after a yearslong struggle, and the residents have been evicted. In fact, it’s actually the third time that settlement was demolished and rebuilt. As one volunteer reminisces, “I don’t know where they go every time.” Palmer himself remembers laying down in front of bulldozers with students in the ‘70s in the same spot that students gathered in 2022 after the Convocation protest. If we don’t remember history, we forget our own place in the larger story of Philadelphia.

It’s easy to forget that our campus stands on top of a neighborhood that people once called home, full of block parties and kids on bikes. Remembering is a means of recognizing the history we walk upon. An elderly woman dusts off her clothing and packs away her brushes, “We’re only here for a little while. You want people to know you existed in this world.”