As historians Alvin and Heidi Toeffler first posited—and my middle school history teacher eventually taught me—there have only been three great changes in all of human civilization. The first came around 12,000 years ago, as humans moved from hunter–gatherers to farmers, allowing permanent settlements and trade specialization. The second occurred around 200 years ago, as the steam engine began the Industrial Age, with urbanization, factory life, and ultimately, electricity. And the third change—in whose shadow we currently live—was computing. Once the personal computer was popularized in the mid-1980s, the Information Age could begin, allowing for global communication and instantaneous dissemination of information.

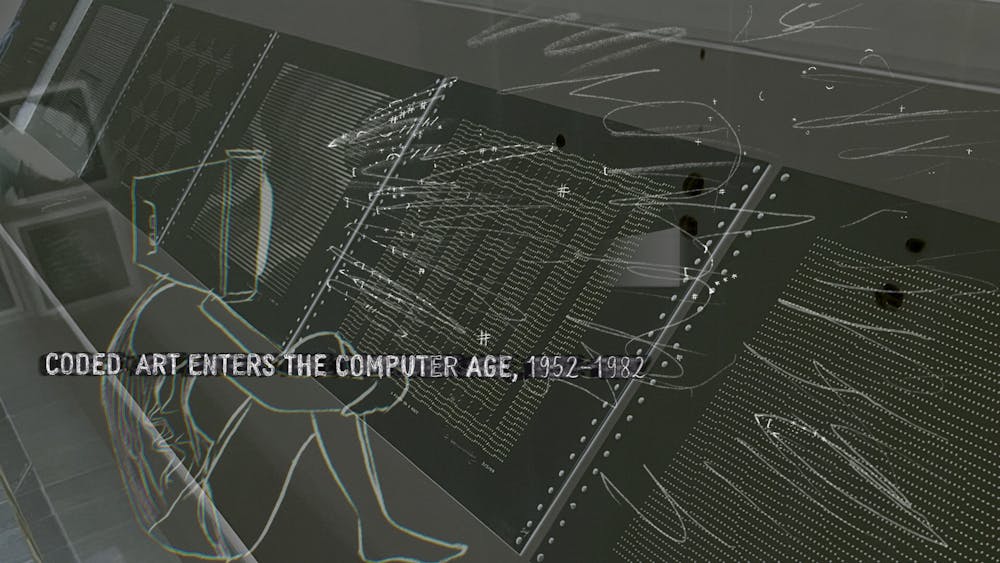

But for each of these changes, there is always a transition period. It can be as long as a few millennia, or as short as a few decades, but it takes time for a new technology to become integrated in society and for its changes to be felt. And it is this transition—specifically, the one from the Industrial Age to the Information Age—which Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, an exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, brilliantly explores.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art—or as everyone calls it, LACMA—has a strong permanent collection of modern art, largely due to the support of local philanthropists like Eli Broad. But what really sets it apart from other museums in the area is its temporary collections, which highlight a variety of topics, primarily a special connection to the local area. And the only thing more synonymous with California than movies is technology; many of the largest computer companies were founded in Silicon Valley, in the northern part of the state, and services companies like Snapchat and Activision Blizzard have headquarters in Los Angeles.

Coded explores how the rise of computers changed art between the years 1952 and 1982. For most people who aren’t hardcore tech historians, these two dates may seem random, but they represent a momentous shift in our relationship with technology. The first “purely aesthetic image made on a computer” was created in 1952, and personal computers largely replaced the mainframe as the standard by 1982.

The interceding three decades were a time of uncertainty and change. Most computers were essentially large calculators primarily used by universities and the military for advanced calculations. Due to their association with the army, much of the art world—which was largely pacifist due to the Vietnam War—wasn’t as fond of the new technology as a medium for creation. But over time, different innovators used ever–advancing computer technology as both the subject matter of (and a tool to make) art.

The idea of technology potentially replacing creative work is a very prevalent one today, amidst the rise of ChatGPT and other advancements. But what Coded implicitly suggests about our own uncertain future is that artists will not be replaced by machines. Instead, technology will assist artists to make works that neither could create alone.

Early on in Coded, I was struck by a piece simply titled Computer Drawings, a 1969 series from Frederick Hammersley. Over the course of dozens of pages from a dot–matrix printer, Hammersley shapes collections of ordinary characters one can find on a standard keyboard (including letters of the alphabet, periods, and slashes) into shapes and patterns. While a piece like this would have been theoretically possible on a typewriter, the holes in the sides of the paper and the precision that was likely perfected over many drafts, makes this a unique product of the computer age.

This is on an even fuller display in Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes, a set of small sculptures from 1974 displaying every variation of a cube with between three and eleven sides. In this work, LeWitt uses an algorithm, which became a popular tool of many artists of that generation. While forcing an artist to adhere to a strict set of rules may seem to run counter to creativity, it in fact enhances it, freeing people to create works free from conventional thinking and allowing the mind to roam further than what was previously thought best.

Not only did computers help artists create, they sometimes provided artists with literal, physical material. This is very evident in Colette Stuebe Bangert’s 1965 work Fortran Statement, a collage of computer punch cards layered over each other. The effect of the different layers of paper, combined with the yellowing of the paper, adds a homey touch, humanizing computers in a time when they were largely seen as cold and monolithic.

But the coup de grace of the entire exhibit is Charles Csuri’s Random War from 1967, which combines the human and computer elements to create a truly special piece. For it, the artist drew hundreds of red and black figures of soldiers, but then used a computer’s random–number generator to place them in different spots—and facing different directions—on a blank white background. The result is a mass of bodies, often overlapping, with guns pointed in just about every conceivable direction. It's holds a solemn message in the age of Vietnam, as war became increasingly random and dehumanized in the face of carpet bombing and Agent Orange.

What Random War and the rest of the pieces on display in Coded show is a period of uncertainty. Most knew that computers had some potential for art—and even the possibility that they could reduce human life into something binary—but few could see the way they’ve taken over our daily lives in 2023. But what that chaos allowed for is creativity, which many very talented artists took full advantage of. And in our age, where people are questioning whether it is possible to work creatively and collaboratively with computers, Coded shows we’re not the first, and that artists have been grappling with this very question for decades.