Writing about HBO’s new show The Idol is a trap. It wants desperately to be written about, packed to the brim with references to modern cultural debates and full of gratuitous sex and nudity. But for a show trying to satirize our modern landscape, The Idol is curiously stuck in the past.

In March, Rolling Stone reported that The Idol, pitched as a satire of fame and the music industry, has been turned into “sexual torture porn” after forcing out its female director, Amy Seimetz. Sources went on to add that Seimetz had been pushed out of the project because the show’s co–creator and star, Abel Tesfaye (better known as The Weeknd), wanted less of a “female perspective.” Tesfaye has denied this.

Seimetz was quickly replaced with Sam Levinson, the new co–creator of The Idol and best known for writing about the kids who are not alright on HBO’s hit series Euphoria. He later declared himself “delighted” by the Rolling Stone reports. At the Cannes Film Festival, where the show’s first episode premiered, Levinson told the crowd, “When my wife read me the article, I looked at her and said, ‘I think we’re about to have the biggest show of the summer.’” HBO tried to lean into the controversy, releasing a now–deleted trailer that called The Idol the “sleaziest love story” in Hollywood.

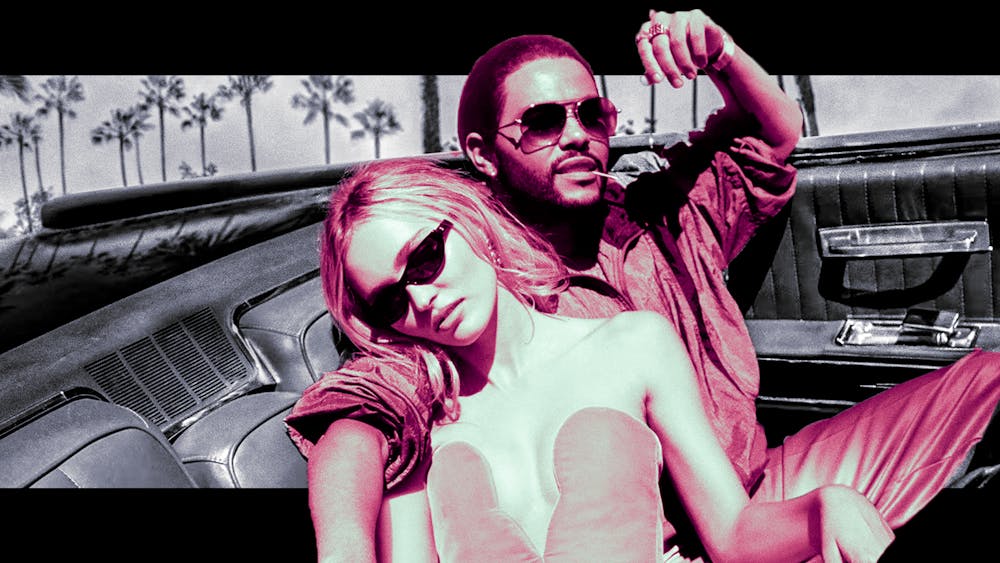

The Idol, of course, doesn’t want for sleaze, but it seems to have Twitter discourse on the mind just as much as sex. The show follows Lily–Rose Depp’s Jocelyn, a waifish sex symbol popstar, recovering from a mental breakdown after her mother’s death and trying to mount a comeback, while beginning a relationship with Tedros (Tesfaye), a club owner and cult leader. In the first episode, she poses nude with a hospital bracelet, while her younger creative director (Troye Sivan, with a surprisingly good American accent) frets over “romanticizing mental illness.” He’s blocked by an older record executive (Jane Adams) who accuses him of trying to “cockblock America” by keeping the public from enjoying “sex, drugs, and hot girls.”

This wade into Internet discourse is on the side of sex, drugs, and hot girls. A twitchy intimacy coordinator is locked in a bathroom after trying to make Jocelyn sign a waiver before exposing her chest. When Jocelyn’s assistant describes her concerns about literal cult leader Tedros by calling him “rapey,” Jocelyn tells her, “Yeah, I kind of like that about him.” Then he suffocates her with a robe to reawaken her creative side. Sleaze via the timeline.

More orgies, cocaine, autoerotic asphyxiation, autoerotic asphyxiation while masturbating, and sex scenes with a fully clothed Tesfaye follow. One assumes that this is supposed to be shocking. Provocative, even. But what really defines the show is paradoxical: its smug assurance that it is meeting the current zeitgeist, while not truly speaking to any modern moment.

The Idol is, on paper, a satire about the cult of stardom becoming a literal cult. While it’s not entirely fair to the show to make bold proclamations about what it wants to say based on only two episodes, so far it hasn’t suggested that it wants to say anything about fame beyond how hellish and/or seductive it can be. And that’s not exactly a groundbreaking statement.

Jocelyn doesn’t resemble any modern popstars. The most famous female musician in the world right now is Taylor Swift, who has traced an image from ingénue to businesswoman without ever stopping at fragile sexpot. Superstars like Doja Cat are open about their sexuality, but not submissively so. Plenty of musicians from Megan Thee Stallion to SZA have been open about their mental health, but they haven’t sexualized those stories. Jocelyn is out of place in our era.

Her closest analogue is Britney Spears (who Jocelyn is compared to several times in just the first episode), which is most obvious in how much the choreography for Jocelyn’s song “World Class Sinner” resembles “I'm a Slave 4 U.” Spears was most famous during a period of intense backlash to movements like feminism. Gender equality was not in vogue, and postfeminism was the new hot thing. The only right for women that mattered was the right to look as sexy as possible.

The Idol is responding to a moment of cultural backlash; against the MeToo movement, against Black Lives Matter, against the right of trans people to exist. From the vitriolic misogyny of the Depp–Heard trial to Elon Musk’s hard right Twitter turn to the existence of Ron DeSantis’s presidential campaign, our current moment is increasingly defined by a resistance to progressive politics and gender equality. In The Idol, it may have finally seeped into our prestige television.

It's no surprise that the show’s other cultural touchstones are also stuck in the past. Lily–Rose Depp claims the 1992 erotic thriller classic Basic Instinct most inspired her while working on the show. The film is even referenced in The Idol’s first episode. Basic Instinct, a classic of provocative softcore cinema, seems to be the standard that The Idol is reaching towards. Erotic thrillers like Basic Instinct seem to evoke a kind of nostalgia these days for a less anxiety–ridden, sexy, cultural landscape. Levinson in particular seems to long for those sleazy days of yore; in 2022 he wrote Deep Water, an erotic thriller starring Ana de Armas.

The show’s truest intentions are to provoke. It wants to poke the zeitgeist, but that’s hard to do when you’ve trapped yourself 20 years in the past, and it seems like you want to stay there. The show seems less like a commentary on modern fame than a wish to return to an era where fame was less complicated. Where it could just be drugs, sex, and girls all the time. What is the problem, it seems to ask? Why not want to return to a time that seems so much sexually free, so much more exciting?

Turn back to Basic Instinct, The Idol’s great inspiration. While Sharon Stone is renowned for her lead performance, it isn’t free of baggage. In 2021, Stone accused the director, Paul Verhoeven, of tricking Stone into the film’s most famous scene—one in which she flashes a group of policemen without underwear during an interrogation. Stone has even said she wanted to attempt to legally stop the film’s release. It turns out that the past isn’t quite so fun and sexy when you consider the real people who lived in it. The Idol is worshiping some seriously flawed idols itself.