What started as a sophisticated night at the ballet quickly descended into a near–riot: the audience throwing objects at the stage, shouting over the orchestra, and even breaking out into fights. This infamous night was the first premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which is now remembered as one of the most controversial performances in music history. To the audience’s horror, Stravinsky had broken all the rules of what was considered good composition, but now this piece is ubiquitous in concert music—being performed this year by the New York Philharmonic and The Philadelphia Orchestra.

Throughout history, musicians have experimented with composition, pushing the definition of concert music even amid controversy.

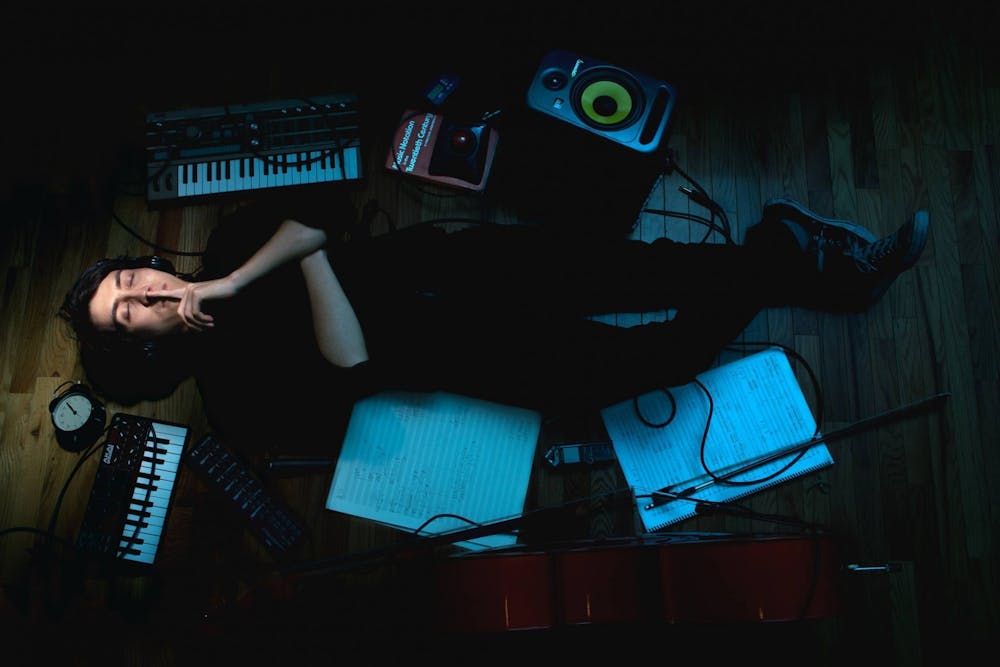

James Díaz, a fifth–year Ph.D. candidate in music composition at Penn, is part of that history as he integrates electronic and modern sounds into classical music. Because he started his music study on a small digital keyboard, his composing process was heavily influenced by electronic music production. He only realized that he had a non–traditional background after he arrived at Penn. “The more I started getting to know other people, I realized that I was doing something that is not that common. But I was like, this is common if you see it from the electronic music or production side,” James says.

James, who was born and raised in Colombia, worked a 9–to–5 accounting job right out of high school. There were no artists or musicians in his family, and he learned how to play piano on a tiny digital keyboard. At 19, quickly becoming bored of his office job, he began putting more time into studying not only piano, but music theory. During this time, he also discovered electronic music production. “That's how I [did] it from the beginning,” he says. “I embrace the computer. It has limitations, of course, but also it opens many other ideas.”

Photo Credit: Mariangela Quiroga

At 20 years old, James was admitted into the National Conservatory of Music at the National University of Colombia as a piano student. When his professor suggested that he was “more of a composer than a pianist,” he decided to study composing seriously.

In Colombia, where there are a lot less opportunities for classical music, James felt like his only option was to compose for orchestras. “In Colombia, classical music is something that is still developing in a way ... usually it’s just the orchestras ... and the universities, but there is almost nothing in between for young composers,” he says. In 2012, the National Symphony of Colombia played one of his pieces through a program for young composers. When he watched them rehearse the piece for the first time, he was astounded. James says, “It was like a wall of sound ... and it was something that I created. And since that day, I commit to [writing] a piece almost every year for orchestra.”

Still, people have tried to label him as an orchestral composer, which he rejects. “I write for orchestra. But I’m not an orchestral composer, because that goes back to traditions that I don’t really belong to,” he says.

After completing a Bachelor’s degree at the National University of Colombia and a Master’s degree in composition at the Manhattan School of Music, he came to Penn to complete a Ph.D., also in composition. Moving to the states was a significant shift for James. These institutions are arguably more fixed in their history and traditions than any other type of modern music performance. Musicians begin training at a very young age, and across these institutions there is a formal repertoire of composers and techniques that must be internalized.

Orchestras and educational institutions tend to stick rigidly to traditional values, but as an outsider, it is easier for James to question the systems that have been taken for granted. “It's very difficult for somebody who doesn't have any idea [of professional classical music institutions], but at the same time, it kind of frees you, because you don't really have any attachment,” he says. James' thesis at Penn continues his experimentation with musical norms. It includes a studio album titled “[speaking in a foreign language]” featuring violinist Julia Jung Un Suh, where he imagines the violin as an electronic synthesizer rather than an acoustic instrument as he brings a new sound to violin music.

As music evolves, classical music institutions are fundamentally resistant to engaging with living composers and programming new pieces. James is frustrated by this roadblock. “[Classical music institutions are] literally like a museum. They present you something that is one hundred, two hundred years old, and they have to keep that tradition. So when do [they] also play what is new?” he asks.

As part of a movement to change the exclusive nature of the concert hall, James was chosen as one of the inaugural composers for this program Composing Inclusion, a joint initiative in New York which seeks to bridge the gap between professional and rising musicians. His piece for orchestra, titled ”and does the Moon also fall,” will be performed on May 6 at the New York Philharmonic’s Young People’s Concert, which reimagines Isaac Newton’s gravitational theory through music. Taking a page out of Newton's book, James leaves us to contend with the known and unknown.

Whether it’s through universal gravity or electronic violin music, the only way to make space for new discoveries is to push preexisting boundaries. James' work tempts the audience to question the fabric of our reality and embrace the possibilities that lie before them. “We are always in movement,” James says. “We need to get out of our narrow perspective.”