In a recent New York Times article, journalist Callie Holtermann writes about the resurgence of Lena Dunham’s HBO dramedy Girls. Holtermann describes Girls as a period piece, of sorts. The period is the early 2010s and the subject is the monolith of millennial post–grads living in Williamsburg walk–ups. For many, rewatching Girls is comforting, affirming the highs and lows of their twenties. The characters are flawed in ways that make them undeniably relatable.

For Gen–Z viewers, however, Girls challenges us to draw the line between comfort show and cautionary tale. Hannah Horvath is an imperfect lead who is loveable and loathsome all at once. When she learns her college ex–boyfriend Elijah is gay, she somehow manages to make it all about her. Soon after, the two become roommates, forming arguably the greatest lovers to friends trajectory in television history.

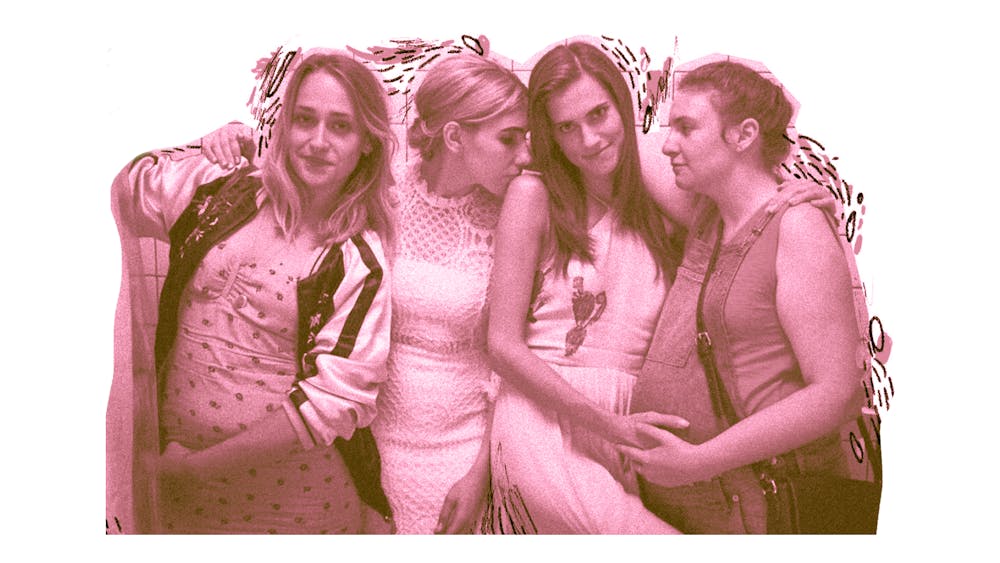

Even when we relate, we despise the four main characters’ most insufferable traits: Hannah Horvath’s narcissism, Marnie Michaels' selfishness, Jessa Johansson’s tendency to self–sabotage, and Shoshanna Shapiro’s prudishness. We hope to not embody the fictional Oberlin College grads, but sometimes, we can’t help ourselves.

As a sophomore in college, watching Girls didn’t give me a model for my post–grad years. Instead, I felt the pressing urge to be different from Dunham’s semi–satirical portrayal of her younger self: a struggling writer learning to be financially independent from her professor parents. She’s impatient, witty, and struggles to keep a job without getting bored or lashing out. She’s a self–proclaimed feminist and social justice warrior, often falling short and blaming others for her wrong–doings. Her dry sense of humor, affinity for colorful and printed clothing, and arms decorated with patchwork tattoos paint her as the perfect 2010s millennial.

While others have the luxury to fear becoming a Hannah Horvath, some of us have to contend with the possibility that we might already be one. Anytime we quietly celebrate someone else’s failure or give up on a task midway through, we become Hannah, abandoning the Iowa Writers’ Workshop after just a few weeks or replacing grief over the sudden death of her editor with the question of whether her audiobook will still be published.

For its time, Girls was revolutionary for not being so revolutionary at all. Dunham explores love, sex, friendship, professionalism, and New York living through the eyes of upper middle–class post–grads. Sound familiar? But what made the show so unconventional was the way it held up a mirror to its audience. Girls was watched and written about by millions of Hannahs and Marnies, forced to reckon with the realities of their own slow careers, discouraging love lives, and expired friendships. All the while, the show’s laughable lack of representation and the characters’ slew of missed opportunities and first–world problems embody an eerily familiar kind of white privilege.

While the first season of Girls premiered in 2012, it's not difficult to envision Hannah and her dysfunctional entourage beginning a post–Penn journey in 2023.

Horvath was a member of the Philomathean Society, a Kelly Writers House frequenter, and an overall insufferable English major. Shosh wasted her afternoons away studying in Huntsman Hall. She spent her junior year summer as a McKinsey summer analyst but graduated with no return offer. Marnie was uptight but misguided. Her face was at every GBM on campus but when met with the question “what are your plans post grad?” she could only shrug her shoulders. Jessa was the elusive international sorority girl. Perched outside of Arch, she’d stare down passersby, blond locks blowing in the wind.

In a Penn world, the unlikely four met during freshman year NSO and remained friends throughout their college years, relocating to New York City post–grad. However, we can’t deny that the group has outgrown each other, forcing friendships that are no longer fulfilling. The episode that demands the most reflection on our own friendships is season three’s “Beach House.” In it, the group visits a family member’s summer home in the Hamptons for a relaxing girls weekend gone wrong. After spewing drunken insults and confronting the pain of growing apart, the four sit in silence waiting for the bus to take them back to their separate city lives.

This episode, and several others, assure us that relationships aren’t capable of being the same after college. In season five, Marnie reconnects with Charlie, her love–smothering ex–boyfriend, after ending things four seasons earlier. They reignite their romantic spark and vow to run away together until Marnie finds a heroin needle in his jean pocket and realizes their love was not meant to stand the test of time.

It’s difficult to accept that no matter how many years have passed since Girls’ debut, post–grad life looks hauntingly similar. We still fear spending four years earning a Bachelor's degree just to relocate to a bigger city with higher rent prices and lower paychecks. Alongside this harsh introduction to the “real world” come the steps we take to understanding who we are. How are we expected to resist self-absorption, sabotage, and the envy of others when our only priority is to fend for ourselves?

Next comes the question: does it have to be this way? Perhaps, Gen–Z viewers can lean into Girls as a work of nonfiction and fiction. Girls shows us not what we could be, but what we should fear becoming, and offers us the choice to change our path.

During my first and only binge–watch of Girls, even the most uncomfortable moments strengthened my emotional attachment to every character. The show requires us to look closely at our ugliest parts but, at its core, Girls tells the story of a group of young people just trying to figure it out.

Maybe that’s why I can’t seem to get myself to finish the last two episodes; in fear of the show being over. When that happens, I’ll finally have to figure things out for myself.