Focus, focus, focus. Read, words, notes. Study. Focus.

I’ve done it. I am in the Moelis Reading Room zone. My mental buzz transcends the material conditions around me. I am studying. I am doing it.

And yet, from the corner of my eye, I see my phone screen blowing up. The joys of technology—perpetual connectivity. The comfort of silence (and Bakunin, one of the founders of modern anarchist theory) can wait.

I reach for my phone and a text glares at me, pulsating with urgency.

“FRED AGAIN IS PERFORMING AT MSG THIS SATURDAY”

Who?

Despite my utter inability to describe this person, I do not hesitate to pull up Ticketmaster, getting in line for this Fred Again male. Whoever he is, I must get tickets. Energy courses through my body, tingling in my fingers as I wait in line. I am number 2,000 on Ticketmaster. Soon it will be my time to purchase tickets to Sir Fred Again. After all, it is Fred Again.

But who is Fred Again? Why has the world stopped, why am I suspended in a titillating game of chance, fighting the Ticketmaster gods to purchase a ticket?

At lunch with my friends, the same energy courses through my body. My friends and I are unable to form cohesive sentences. The name Fred Again is repeated with such frequency that his spirit imbues the air with a very tangible energy. We look at each other, somberly agreeing to pay up to $150. Again, I am not really sure who he is.

One hour, two hours. We get into the Ticketmaster heaven and yet the system crashes. The gods don’t bless us with tickets. The air that was charged one second ago collapses. Empty vacuum. Faces crumble. No Fred Again.

No worries. It was just a concert. Just a concert that sold out Madison Square Garden in less than two hours. Just a concert.

My friends and I get a text later that evening. $125 each for four tickets. Take it or leave it. The air is charged again. We take it. Who is Fred Again?

Post–ticket mania, I google Fred Again. I do know some of his songs! Fantastic, money well spent.

The rest of the week a strange feeling comes over me. Despite my utter inability to explain who Fred Again is, what the stuff of his music is and why he held the ability to tear me away from the tranquility of Moelis, Fred Again assumes, in my mind, the position of a status good. I casually ask friends if they’re going to his concert, nonchalantly throwing his name out and proudly, yet subtly (I don’t want to be too ostentatious) mentioning that I did indeed manage to acquire tickets. I am going, you are not. Don’t worry, next time!

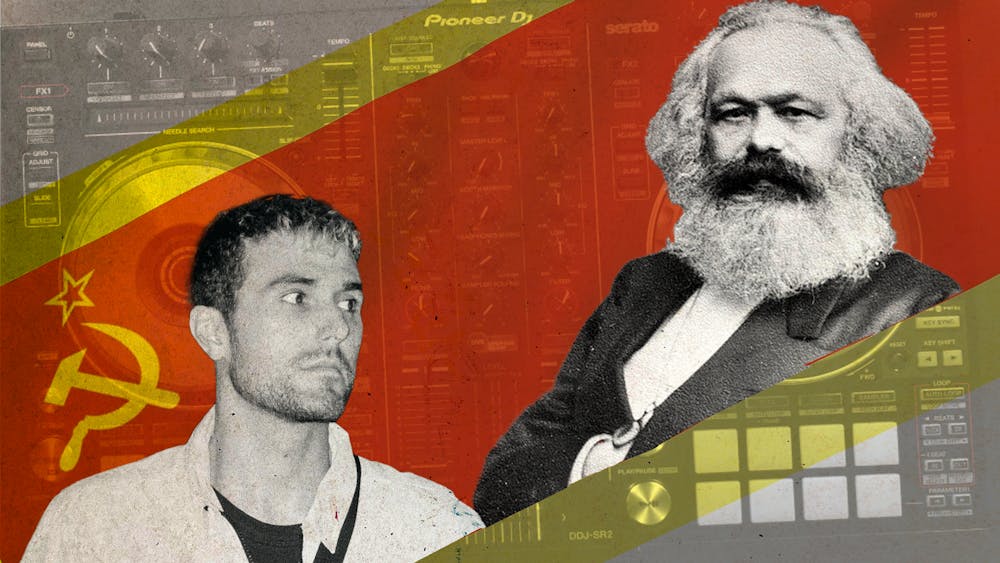

The phenomena are strange. How is it that Frederick John Philip Gibson, the 29–year–old DJ, single handedly sold out Madison Square Garden with a two–hour notice within two hours? How did Mr. Gibson manage to create an informal market with astronomical prices completely at odds from the actual use–value, or material value, of his product? And why has his name, rolling off my tongue with a soft confidence, come to assume a value equivalent to any Moncler, any Canada Gooses, any Balenciaga school bag? Sure, it’s Fred Again. But why?

These are big questions, questions that consumed Marx for more than ten years and cost him several boils on his rear side. They are the stuff of his four volumes of Das Kapital. So how can we begin to tackle these questions, explain what happened in the span of four hours on an otherwise calm Wednesday afternoon? Marx would attribute this phenomenon to none other than commodity fetishism.

Despite Fred Again’s lack of support from many true DJ fans, his ability to construct artificial hype enabled him to transform his concert into a commodity—one comprised of use value and exchange value that can be bought and sold in markets. Through the mechanisms in these markets—in this case the dual Ticketmaster market and informal market created—an arbitrary value for the concert came to exist, a value innately at odds with the intrinsic worth of the concert and, equally, the inputted labor. After all, how can an arbitrary number, $125 for example, possibly capture the value of music, mired in art and sound and experience and music? How can it capture the amount of labor involved, from Skrillex’s Tumblr–reminiscent performance to the onstage light show, the very social relations constituting the concerts?

The answer is that this arbitrary number cannot convey the real value of the concert. It’s just a made–up product of capitalist market forces. Its consequences, however, should not be taken as lightly.

Consider the interplay between music as art and capitalism—are these two notions not antithetical, music representing an art of high form that should remain unscathed by capitalism? Marx cannot help but agree. Though he might have opted for Chopin or Schubert as his choice of music, the fact remains that Fred Again constitutes music in this day and age. Yet, the reselling of Fred’s concert had the very effect of allowing music as art to fall prey to capitalism and wedding art in a quest for profit. Despite the concert being incredibly fun, with Fred’s music possessing me in a quasi–spiritual experience, the bureaucratic procedures surrounding Fred’s concert screamed profit–making.

The effect? The concert and the term Fred Again transcended the very art they were mired to, transforming into high–value commodities in and of themselves, uplifted by the clamoring arms of fans clinging to the purported hype of Mr. Gibson. His actual music? Secondary to the phenomena occurring.

As such, on that fine Wednesday afternoon, I did not buy a concert ticket. I invested in a commodity with short–lived social status, encouraging the ultimate modern expression of abstraction from art, allowing said "art" to transcend its innate form and assume a shell of value. Nice.

But why exactly did this reduction of art as art occur? In other words, why was I gripped by a fervent need to wait for 2,000 people to buy tickets just so that I might get a chance? Though social media hype and marketing no doubt play a role here, Marx posits that it is the phenomena of commodity fetishism that enables this feat. The monetary number attributed to tickets by Ticketmaster exists at odds with the true amount of labor input involved in the concert production. Ticketmaster did not bother to ask questions about the social relations involved, and neither did excited resellers, reducing the concert to a superficial relationship between concert as commodity and ticket buyers.

The labor, the real life, the human core of the product became obscured. Instead, the market value of the commodity became the inherent property of the commodity itself. The concert, in the eyes of ticket buyers, became a mere shell of value, abstracted from its artistic art value and labor input. Through this arbitrary allocation of value, these commodities come to appear more valuable than they are, evidenced by the fact that I dropped Bakunin in honor of said Fred Again. A mystical quality to say the least.

A big cheer to Fred Again, a concerto of capitalism orchestrated by a master capitalist who steered my little queer leftist self on a bus to New York to experience two hours of bopping in the flash of the stroboscopic lights of Madison Square Garden… all before spitting me back to Philadelphia in a 3 a.m. Megabus. Capitalism may fall short in a lot of regards but it is, indisputably and admittedly, fun. Sorry, Marx. Well played, Fred.