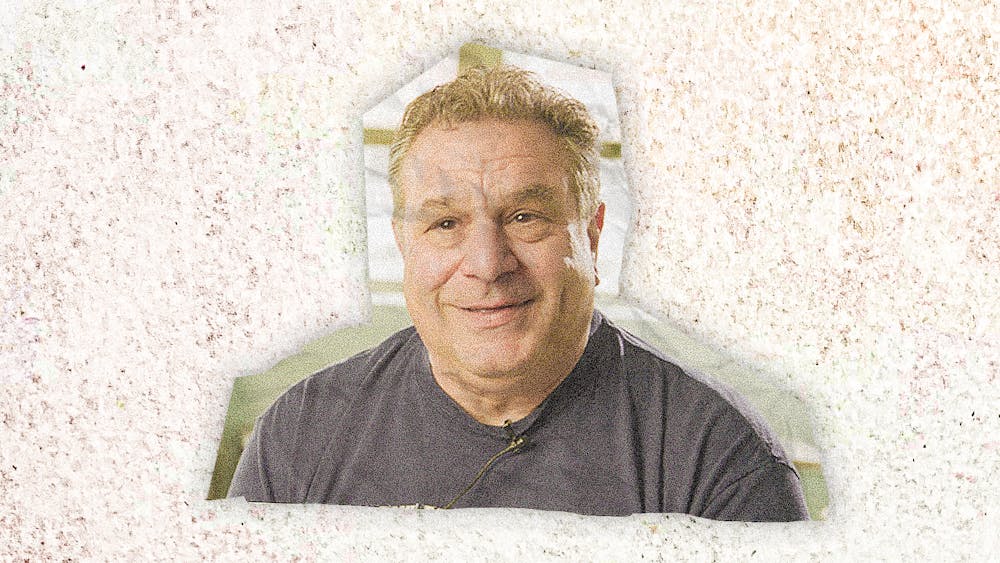

At 42 years old, Lou Lozzi found himself as the “oldest kid in class” studying urban and multicultural education at Eastern University. Inspired by his childhood at his father’s auto repair shop in South Philly, Lozzi chose to leave the corporate world in order to teach. Upon completing his Master’s in Education, he worked for eight years at charter schools until Rich Gordon, the principal of Paul Robeson High School in West Philly, asked him to lead their math and science team.

Lozzi has worked at Paul Robeson High School for the past six years, a time of immense growth and change for the school. In 2013, the school was slated for closure, but in the past five years, the school has received over 40 awards and recognition from Governor Wolf, Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia. In 2017, it was the most improved high school in Philadelphia.

Lozzi played an enormous role in this improvement. Each year, over 85% of students entering ninth grade at Robeson are predicted to be below basic in math and science skills. This school mainly serves teenagers from the local area: According to the school’s principal, 100% of their students live in poverty. Lozzi compares their experience to his own high school experience. He reflects, “You know, my only job was to do well in school. But [Robeson] has a population of teenagers with so many things in the way.”

The foundation of this growth rests on the learning programs that Lozzi started in collaboration with the Netter Center at Penn. He’s currently working on nine different collaborations, including Academically Based Community Service (ABCS) courses, Moelis Access Science, and STEM courses at Cobbs Creek Community Environmental Center.

Lozzi worked closely with Lori Flanagan-Cato, an associate professor of psychology at Penn, to bring Robeson students to Penn to learn in engaging activities with current Penn students. In ABCS courses like Everyday Neuroscience, Robeson high schoolers come to Penn for lab experiments, small group work, and review quiz games. In Math 123, Penn students create and run lesson plans to help Robeson students prepare for the Keystone Exams, Pennsylvania’s standardized tests. In these classrooms, there are as many Penn students as there are high school students. For Lozzi, this is the most important part of the system: “You notice when you've got 24 high school students and 24 college students, they can't get distracted. And it really just blossomed from there.”

Replicating these programs, though, requires Penn students to teach and participate; Lozzi doesn’t want these programs to die as Penn students cycle in and out. For a lot of the high schoolers, it’s not just academic enrichment: It’s fun, and it’s new. “We have ninth graders that are like, ‘Hey, can I do that?’ ‘No, you pass your algebra Keystone, then you can join the engineering team next year.’ We have to make sure there’s a next year.” From product design in Tangen Hall to gene research in Leidy Labs, these collaborations offer unique opportunities outside of the typical classroom experience.

For now, there's a good reason why most of these programs are hosted on Penn’s campus. Lozzi points out the limitations of the Robeson High School building: “Our biology lab’s got two outlets. Two outlets.” Robeson has only recently gained air conditioning after years of community activism by students and teachers, and this year, the Philadelphia School District will fall short by over $1 billion on funding.

With their systems falling short, Lozzi works constantly to create learning opportunities for his students. As the Philadelphia School District faces declining academic performance, Lozzi’s collaborative solutions are a much needed innovation with 6 years of data and national recognition. “What I want to see is us develop these types of programs with other universities, and other schools … We found a real solution to what’s happening in urban Philadelphia in terms of education. It works.”

Lozzi wants to see a larger commitment from Penn towards urban education. As Penn continues to expand into West Philadelphia, Lozzi wants to see funding to build up local schools, rather than tear them down. “As Penn continues to build west, my fear is you just want to bulldoze us,” Lozzi notes. With Penn, Drexel, and Temple’s presence in Philadelphia, Lozzi urges the schools and their students to apply resources to the communities they occupy. “If these kids are educated in their own neighborhood, they can become an integral part of the growth that’s going on. Allow our students to become the next engineers, the next set of physicians.”