“AI is the natural progression of evolution for humans. It is the next species.” My friend tapped his cigarette. We sat by the BioPond, looking up at the nerve–like branches of the trees—brains stemming into the sky. In the generation of OpenAI, with programs like ChatGPT or Dall–E, artificial intelligence is becoming more and more indistinguishable from our own DNA. As we question what this means for the human community, artists at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) have some answers.

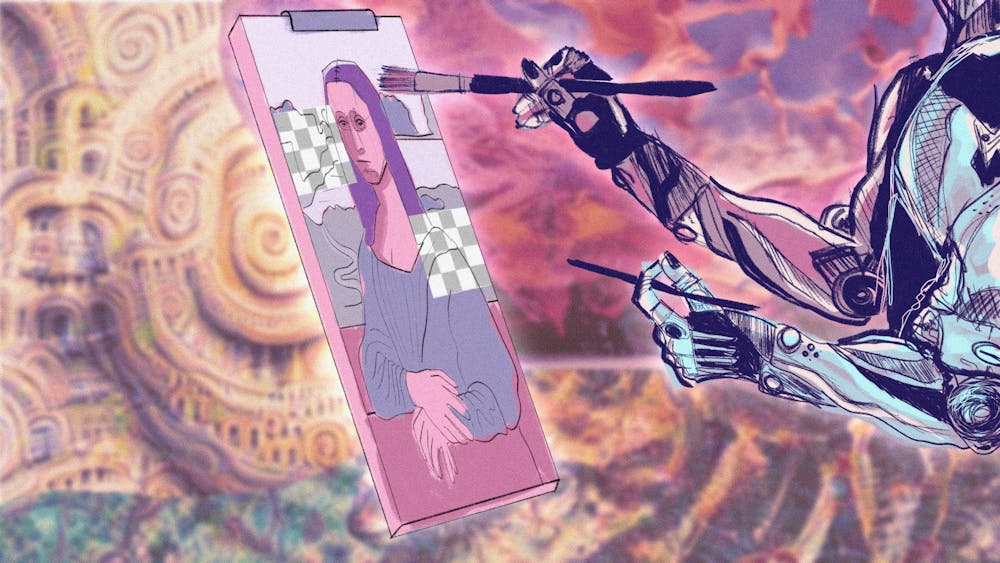

In the relationship between technology and visual art, the artist has always been the master of their medium—whether it was the introduction of film or digital drawing software. Now, the two are equals.

Walking into the MoMA in Midtown Manhattan, an ethereal hum guides you to a wall with a projection. What you see will never be repeated again: For one moment, the screen is a network of colorful strings. At another, it’s a shimmering pastel glop—like what you see when your eyes are closed.

The art installation, which runs until April 15, is Unsupervised by Refik Anadol, in which a “sophisticated machine–learning model” interprets all of the data of the MoMA’s collection in live time. The screen itself looks like a new being in a lab: grainy, streaked, and breathing—thoughtless, but visibly alive. Although it is without form, it has that faint quality of sentience that makes it feel as though it could be related to us.

Anadol explains that while AI was invented for realism, what happens when it explores “fantasy” or “hallucination?” To him, the irony of AI is that although we are entrusting it with predictions of the future, its absence of collective memory makes it disconnected from us. By teaching it the history, it will not only project the future of art, but also tell us what it could have been. Through the draped, splattered, and bubbling colors, he makes alternate timelines of human creation we could never imagine ourselves. (And it is a popular site for Instagram boomerangs.)

In another room, “Anatomy of an AI system” is a realistic and intricate study of the process of assembling, using, and disposing of an Amazon Echo. But Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s system includes much more than the details of distribution and production.

In between the details of a black and white diagram that spans an entire wall, the system analyzes the abuse of human labor and exploitation of ecological resources in plain sight.

The work features bullet points of Marx’s critique of capitalism, an image of the earth’s core signifying “deep geological time” and the profile of a phrenology diagram. The longer you stare, the more you realize there is a line connecting you to the picture’s endless flow charts. Crowning the work is “Human operator,” and, like a new machine with a packet of directions, it has “Issues.”

Unsupervised by Refik Anadol, 2022.

The “system” is a warning for an impending choice: Will we allow technology to become closer to us, or will we make ourselves closer to technology? The more AI emerges, the more we have the ability to find the emotional and soulful landscape that could exist within it. This would mean using it as a canvas to reflect upon and define the human experience, as art always has—or we can digitize and numb the human experience by letting AI dream it for us.

Beyond these meditations on AI, galleries throughout the MoMA are consumed with newfound relationships between technology and art. From an architect's blueprint of how to design homes if angels migrated from heaven to New York City, to a documentary about a Google employee’s investigation into the class divides between workers, artists are adapting to AI.

Embedded in their art is an urgency that technology can outrun us, but perhaps art is the only realm in which we can reclaim control.