The Oscars are having an identity crisis.

Over the last decade, they’ve been called out of touch, too populist, too pretentious, self–serving, and far too white. The organization reportedly went through a collective period of soul–searching after #OscarsSoWhite landed in national headlines, and efforts to diversify the new voting body have sent its tastes swinging between generationally defining and socially propulsive films like Moonlight and Parasite—and whatever you’d like to call Green Book.

But although celebrations of non–white narratives represent changing tastes in storytelling, those trends don’t always apply to the marginalized bodies that occupy those stories. This phenomenon is particularly egregious at the Oscars: only four men of color have won lead acting awards, and Halle Berry is still the only woman of color to win a leading actress award in 95 years.

So, it was rightfully inspiring when Michelle Yeoh became the first Asian woman ever nominated for the Best Actress Award, for A24 smash hit Everything Everywhere All At Once. This science fiction tale about a Chinese immigrant mother falling apart and pulling herself back together again has put Yeoh at the forefront of the awards conversation. After conquering world cinema in films like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and Crazy Rich Asians but still failing to please Hollywood insiders, she’s finally in that rarified space of self–congratulatory award shows.

Whatever your opinion of the Oscars (boring, out of touch, too white), it's hard to deny the power of this narrative. Yeoh will chase "award show glory" through the power of Asian and Asian American cinema—far too long dismissed and regulated to the back of the Hollywood ballroom. There’s a bittersweetness to these nominations that Yeoh herself has often mused on, the joy of making progress contrasted with the weight of carrying everyone else who has come before you.

Yeoh is a frontrunner partly due to her outsider status. But on the morning the nominations were announced, Hollywood proved that it was just as interested in rewarding insiders. The most shocking moment of the announcements was the nomination of little–known British character actress Andrea Riseborough.

An Oscar for an acting performance is voted on and bestowed by an actor’s peers. Ultimately, the respect of your fellow actors is what gets you that little gold man. That admiration is what catapulted Riseborough into the Oscar conversation in the span of about two weeks.

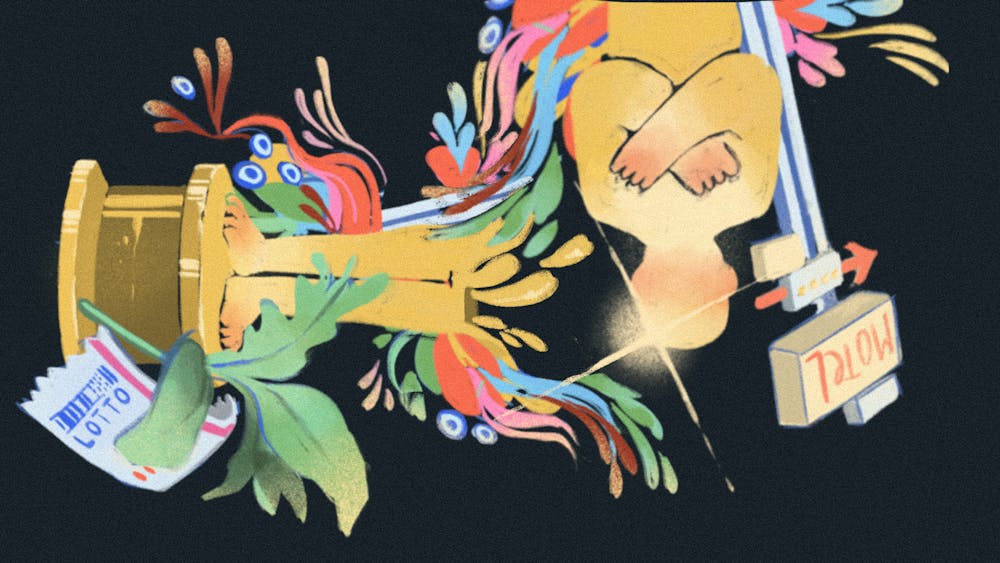

Riseborough’s surprise nomination came at the apex of the year’s strangest and most surreal campaign. She starred in To Leslie, a film following an alcoholic mother who wins the lottery and squanders her spoils. If you’ve never heard of it, don’t worry: It made twenty–seven thousand dollars at the box office, just around half the salary of the average Penn grad.

Riseborough’s movie didn’t have the money for a traditional campaign, but it did have an army of Hollywood A–listers. Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Aniston, and Kate Winslet all posted adoring paragraphs to social media, held screenings, and even moderated interviews with her. Oddly, most of these posts had similar language, suggesting a cut–and–paste situation—but To Leslie can only be called a ‘small film with a giant heart’ so many times. Was this some kind of conspiracy? Blackmail? A case of movie stars lacking a wide range of adjectives?

The answer, of course, is more familiar. Riseborough and her director Michael Morris are well–respected industry veterans. Riseborough is something of an actor’s actor, meaning she’s your favorite actor’s favorite actor. And as it turns out, money isn’t everything if you’re pals with Jennifer Aniston.

But Riseborough’s surprise nomination seems to have come at a price. Many of her celeb friends posted about how Black actresses like Danielle Deadwyler (Till) and Viola Davis (The Woman King) were guaranteed a nomination, but that narrative didn’t stick when the results were announced. It’s impossible to say that an actress could replace another in the race: Nothing is ever guaranteed at an award show, but the absence of any Black nominees was startling when coming from an industry that preaches dedication to racial equality but can never back it up.

Davis and Deadwyler did everything right when it came to campaigning for that award: the right dinners, dresses, interviews, and precursor awards. Celebrities in the press praised Riseborough’s “grassroots” campaign in favor of traditional pushes, but it’s hard to call a campaign created entirely in an insular group of very famous friends “grassroots.” It’s also worth considering if this type of campaign could produce the same results for Black performers.

So does this feel–good narrative about the industry supporting one of its most underrated performers really feel good? And if a Black actress, like Davis or Deadwyler, does everything that they are “supposed to do” on the campaign trail and is still turned away in favor of a white actor with a lot of friends, can they ever get in? Will this system ever reward Black women?

The Hollywood machine is made to insulate itself from the possibility of change. The Riseborough nomination did not come from a desire to recognize inequity in campaigning, but from the traditional impulse of an overwhelmingly white voting body to rely on their networks and friends to tell them how to vote. Given that the Academy has pledged to promote actors of color, it’s important to realize that handing out one consolation prize a year to promote “representation” in the industry does not rectify institutional desires to favor whiteness.

Awards recognition is a sign of respect from your industry and your peers. The Oscars tell us, each year, what ideas and which people the most popular and famous members of our largest media industries consider valuable. When will Hollywood consider women of color valuable?

If there’s any justice in the world, Hollywood will answer the aforementioned question for us on March 12. Michelle Yeoh puts it best: “Please frigging give me the Oscar, man.”