Sarah Kane (C '23) sheepishly admits that she entered the world of science because of the cult classic series Star Trek. In particular, as a young kid, Sarah felt most deeply connected to Star Trek’s blind engineer. “It was the first time I had seen a blind person represented in science like that,” she says. Born legally blind, Sarah continues to defy barriers to pursue her passions in physics and astronomy.

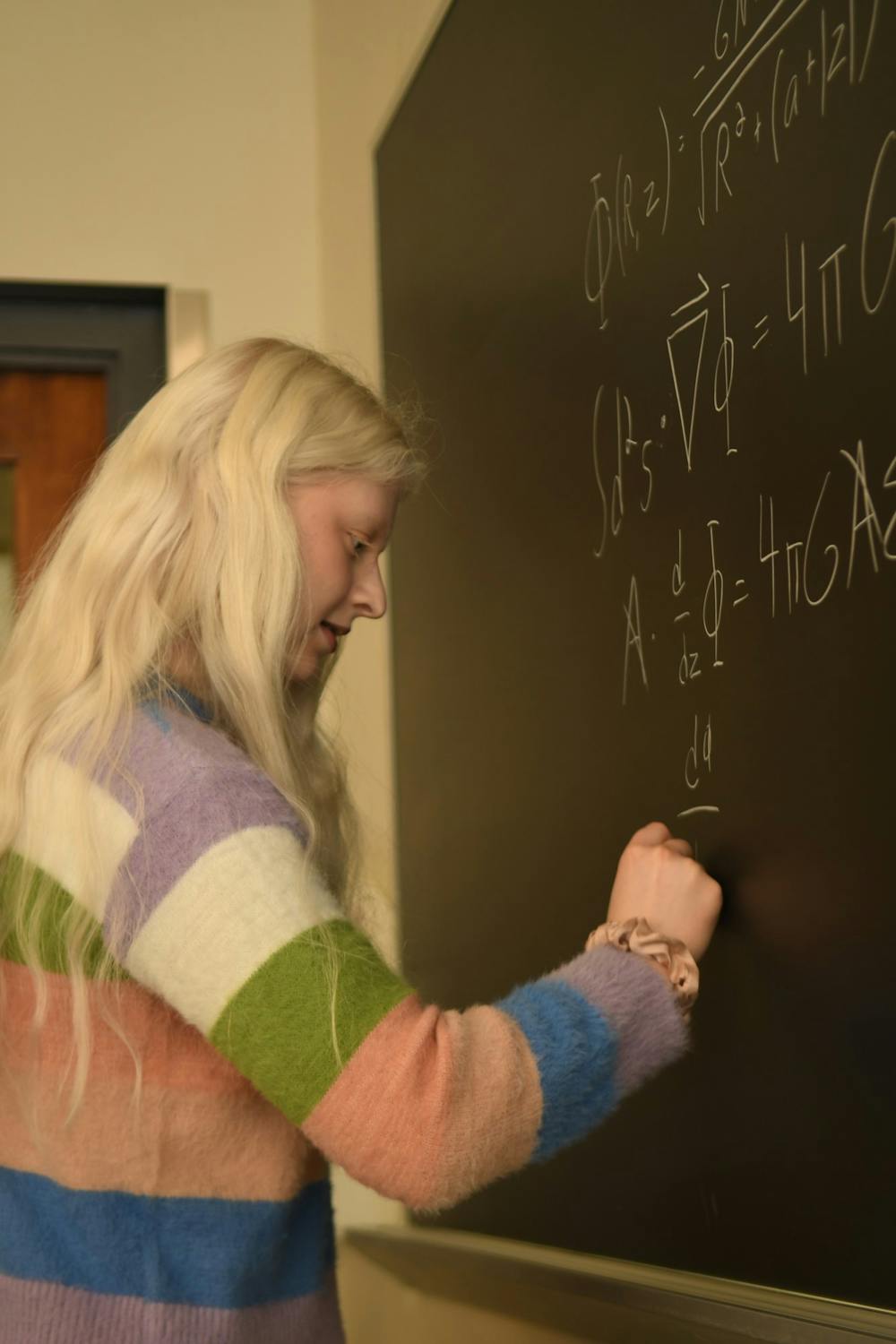

Sarah began her research at Penn with professor Bhuvnesh Jain in the galactic archaeology field, which focuses on the structure and formation history of the Milky Way. For her senior thesis, Sarah is using a machine learning algorithm to look for metal–poor stars, typically the oldest stars in the galaxy, to gain insights into the earliest stages of the Milky Way's formation.

Yet despite her groundbreaking work, Sarah is keenly aware of the barriers that exist in science as a blind woman. She notes, “Generally, we visualize astronomy data. We make it a plot or a graph or an image. And that’s not super accessible.” Shortly after her first year at Penn, Sarah was introduced to Astronify, an initiative that specializes in sonification: transforming types of astronomical data into sound with the purpose of making it accessible to blind people. “That really—pardon the pun—opened my eyes to this broader world of disability advocacy within science,” she says.

For over two years, Sarah has worked as an accessibility tester for Astronify and is passionate about the intersection of science and disability advocacy. “There’s value in advocating for the inclusion of disabled people in science,” she says. Sarah has also worked to lead initiatives in order to connect visually impaired individuals with opportunities to pursue science on campus, including coordinating a trip for students from the Overbrook School for the Blind to Penn’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

While Sarah diligently works to reach scientific breakthroughs, she is not afraid to shy away from challenges in her own life. Sarah, who has used a cane her entire life, claims that one of her bravest feats was choosing to get a guide dog from The Seeing Eye before her sophomore year. “It was quite scary to decide to get a guide dog,” she says. “It was frightening to change something from the way I'd always done it [and] to trust an animal to guide me around rather than a cane, where you are really relying on your own senses.”

As she sits beside her guide dog Elana, Sarah reflects that she leads her life through faith in others. “I'm trusting that people aren't going to try to interfere with my guide dog. As a small blind woman, I'm trusting that people aren't going to behave badly towards me. I'm trusting that if I stopped someone on Locust Walk and asked for directions, they'd stop and give me a hand,” she says. “Sometimes that trust is met with disappointment, but oftentimes it's not.”

As Sarah heads off to earn a PhD in astrophysics at the University of Cambridge next fall as a Marshall Scholar, she can’t help but ruminate on her beginnings.

“I got interested in science because of a fictional character on the fictional show Star Trek. It was great, but it wasn't real," she says. “I didn't know that other blind people in astronomy existed, and didn't know that anyone would care about making it so that we could be here.”

Sarah strives to be a role model and advocate for others, promoting resources for more disabled people to get involved in science. “What is most enjoyable and rewarding for me is the idea that I am holding open the door for the person behind me. Hopefully, the next little blind girl who wants to study astronomy won't have her only role model be a character from a fictional show.”