The audience sits tight in Kelly Writers House, neatly tucked away from the bustle of Locust Walk, in an appropriate sanctuary given the guest speaker that will be coming in any second now: Ling Ma, the author of Severance and Bliss Montage, reputed for her astute and poignant criticism of modern society. Ma’s writing style effectively transmits the somberness of our modern condition through the coquettish use of satire that simply yearns to be read with ease, never sacrificing one for the other. Her impressive ability to interweave the dark and the light is not lost on contemporary readers, and she boasts handsome accolades including winner of the 2018 Kirkus Prize, a spot on New York Times Notable Books of 2018, and being shortlisted for the 2019 Hemingway Foundation.

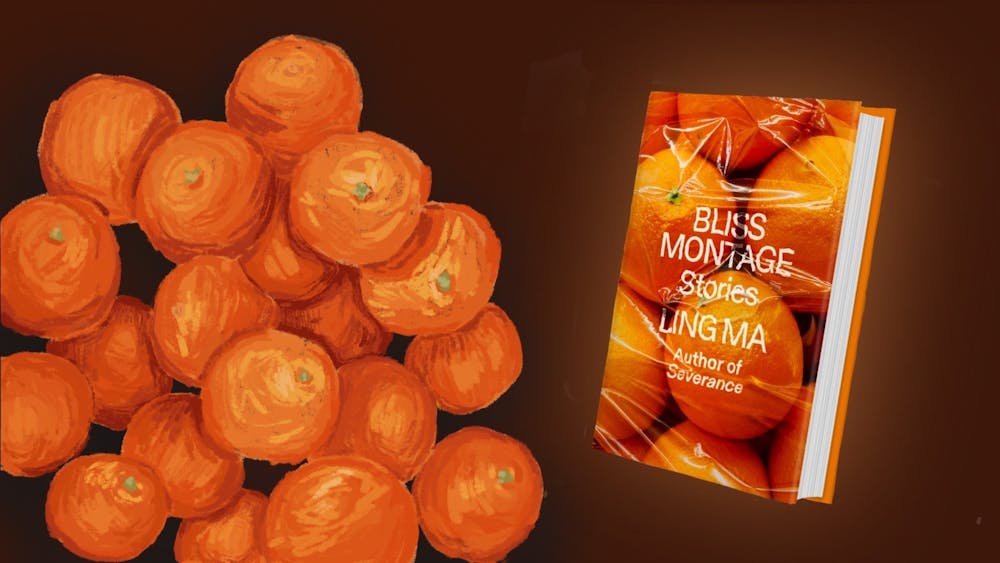

There's a subdued air at the event, conversations hushed yet charged with the soft murmur of excitement. The audience twitches with an almost palpable energy—hands and feet fidget, torsos sit upright, bodies tense with bursting energy. Stacked Bliss Montage copies line the room, each person eagerly awaiting Ma’s reading and subsequent Q&A. Will they get a glimpse of her brilliance, of the inner workings of the woman behind these books?

Severance’s blend of tropes is marvelous. Candace Chen, the protagonist, is a young woman working and working and working in New York when her world is seized by a COVID–like pandemic induced by the ever–spreading Shen Fever. As the outbreak continues, turning people into consumerist zombies that endlessly repeat the most extreme symptoms of capitalism until their putrefaction (including engaging in endless consumption and watching TV), Candace flees the city with a group of survivors.

Through this painfully familiar setting, we follow Candace as she navigates the mind–numbing aspects of corporate culture and the ultimate futility of work. Pre–pandemic, we see her lived experience of modern capitalist exploitation, following her monotonous routine and obsession with brands. Post–pandemic, we see her fellow LinkedIn friends stuck in equally mind–numbing consumerist routines, utterly alienated from their labor. Her book, in this regard, cannot help but be read as an acute and relevant commentary of late capitalism.

And yet, Ma weaves further nuances into her novel, presenting Candace’s experience as a Chinese American in an honest and simple way: a fact of life. Ma tells us Candace is invited to a shark–fin soup dinner party, organized by a wealthy Chinese businessman, rife with disheartened New York City corporates searching for enlightenment. It's a dinner party not mired in cultural wealth and an accordant celebration of Chinese culture, but rather an event where this cultural emblem is presented as a social commodity and conduit for networking: the ultimate severance from culture and its fetishized repackaging into a social token.

Equally, in a ‘surprising’ twist, Candace’s firm sends her to China to negotiate a bible book business deal, in what invariably reads as a comical plot sequence underscoring the absurdities of neocolonialism. It is in these very moments—at home, in China, and across temporal frames—that we see Candace grapple not only with the phenomenon of one’s alienation from labor, but equally the gravity of alienation from one’s culture and identity. In these moments, Ma presents a striking exploration of the immigrant experience and the way in which Candace’s identity rests very much on an imagined China, spatially and temporally dislocated.

Despite what reads as a beautiful criticism of capitalism, so poignant to our modern condition and so raw in its presentation of life, Ma does not read her book as such. Nor, more heartbreakingly, did she write it as such.

I scribble my question in the notebook precariously perched on my lap, calling the moderator over. I’ve thought long and hard about her book, done the readings (dear old Marx), and am certain that what I will ask will cut to the heart of the book. I will reach Ling Ma through the blinding haze of her superior intellect. This is my time.

“Did your book Severance begin with an acute criticism of late capitalism and our subsequent alienation from capital or as more of a general exploration of its conditions? I ask because elements of the book remind me of both Marx’s Capital, Volume 1 and equally Graeber’s anarchist texts. Did you intend it to be read in this expressly political manner or do you have any thoughts regarding this reading?”

Silence.

Ma stares back at the audience before sharing that in reality, Severance is merely an exploration of her Candace’s—our Candace’s—anger about work. She explains that she views her novels as opportunities to give these characters and their struggles the space to live out their realities. In other words, Severance (as the novel) functions as the fictitious set of boundaries against which Candace’s story unfurls, while Ma’s words function to activate the action within this space. Severance merely exists as a product of Candace’s journey and the words Ma has given her, in what can only be understood as a dynamism between author and fictitious subject.

The disjuncture between Ma’s work process and the meaning we attribute to it, overflowing with analogies for capitalism and our present state, point to our postmodern tendency to assign meaning to any form of art. More importantly, this lackluster moment of truth should be cause for reflection: Are we merely constructing and extracting an elaborate meaning from Severance, or is that meaning a reflection of the very things we witness around us?

In other words, does Severance function as a mirror of that which we feel regarding our present everyday lives—the tangible woes of corporate culture and capitalism? If this is the case, Severance—and her new collection of stories, Bliss Montage—should be, above all, read as a warning call.