Despite having been painted more than 150 years ago, Édouard Manet’s Olympia continues to resonate throughout the art world. In 1865, the painting debuted in Paris’ prestigious Salon, controlled by the French Academy of Fine Arts, immediately scandalizing the scene. The work subversively approached the reclining female nude with its daring technical, stylistic, and thematic choices. While she was created by a man, Olympia has consequently joined the ranks of groundbreaking and influential women, both in the art world and beyond.

Newspaper critics at the time were quick to scrutinize the avant–garde painting as one that broke from tradition—and not in a good way. In contrast to conventional works which prioritized naturalism, impeccable technique, and classical subject matters, Olympia boldly and overtly rejected tradition with its aggressive, imperfect brushstrokes and harsh lighting and coloration. But, while Olympia certainly breaks with artistic predecessors, it still references tradition—just not in a manner the Academy appreciated.

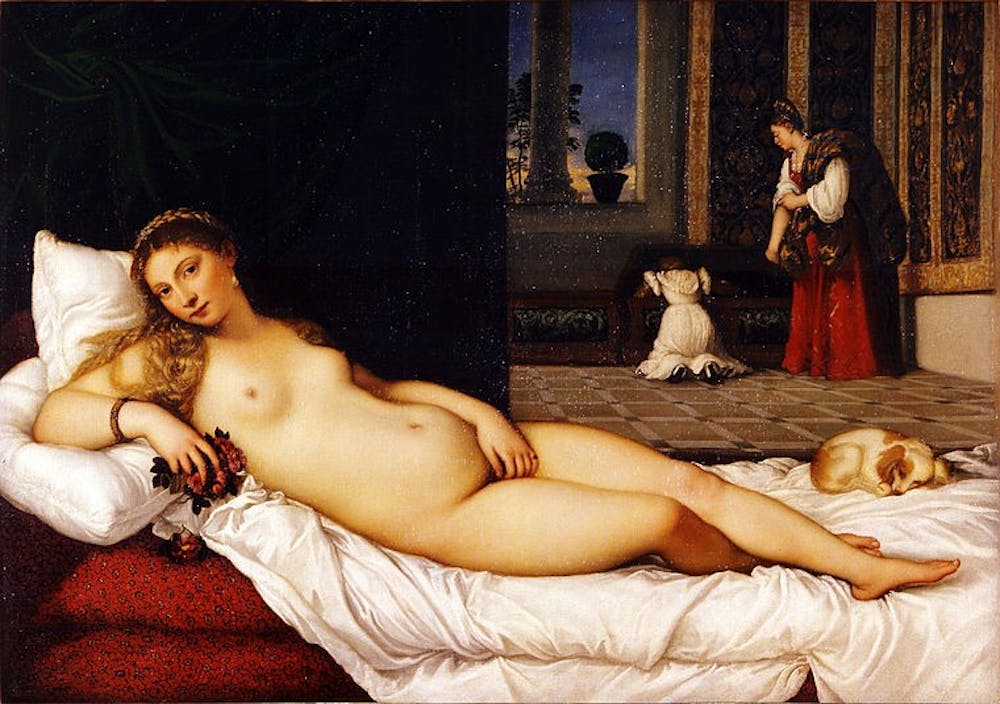

Clearly inspired by Titian’s Venus of Urbino of 1538, a pious, sensuous representation of Venus, Manet created his own warped version of the figure, stripping what once was a goddess of her moral purity through subtle sexual details.

André Dombrowski, Frances Shapiro–Weitzenhoffer Associate Professor of 19th Century European Art, describes Manet as "the artist who is perfectly aware of tradition, and actually cites it very deliberately, but at the same time updates it in a way that it doesn't exactly become unrecognizable. But there's also a high degree of disruption.”

Specifically, situating the title of the work within its historical context reveals that the sitter is a courtesan. The figure’s stark, pale skin tone (especially compared to the warmth of Titian’s Venus) shocked critics, who likened her to a corpse. Manet does away with Titian’s soft, blended technique using textured brushstrokes which give the work a sense of harshness. Olympia defies traditional notions of femininity, with stubble under her armpits as well as dirty hands and feet. While Venus lays clean, pure, and comfortable on her impeccable couch, Olympia does the opposite. She is stiff, sitting upright on wrinkled sheets.

She covers her crotch with ownership and power, seen in the deep shadowing of her hand that indicates it is flexed. Venus, by contrast, lays her hand gently and in a position many have characterized as inviting, complementing her sultry gaze. Most starkly, Olympia is confrontational—a demeanor, particularly for a sex worker, that was unacceptable and baffling to the French art world at the time. Even the black cat at the edge of the bed offers a contrast to Titian’s Venus, who lays with an adorable puppy by her feet; it symbolizes deviant sexuality as opposed to fidelity.

While the reclining female nude is an artistic motif portrayed time and time again even before Manet was born, through technical and thematic subversions, the artist effectively stirred controversy that, depending on your perspective, either marred or revitalized the trajectory of art. Professor Dombrowski explains this phenomenon: “From the moment Olympia is shown in the Salon of 1865, it becomes kind of the touchstone for avant–garde representations of female nudity,” he says. Some artists who interpreted and responded to the work in later art history include Paul Cézanne, in his A Modern Olympia (1874), Paul Gauguin in Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892), and Henri Matisse in his Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) (1907).

But while Manet and those inspired by Olympia previously mentioned above certainly dismantled artistic expectations with an avant–garde approach, many gendered norms at the time remain intact in their works. Professor Dombrowski gives some much–needed historical context: “Remember that when Olympia is painted, women cannot vote. There is almost a complete disenfranchisement of women in the political sphere, but also in the artistic sphere. The Academy of Fine Arts in France doesn't admit a woman until much later in the century,” he says. “This has produced a 19th century in which the presumed position from which one paints, from which one looks, from which one buys sex from, from which every kind of commercial and emotional transaction originates, is male… And for all the kinds of questioning of tradition that Manet does, he does actually quite little to interrogate or to dismantle that overarching presumption he's working with.”

Olympia cannot be blindly considered the pinnacle of revolution and subversion in painting. However, it shook tradition with its overt sexuality, sending ripples in the art world. Because she started to toy with social and artistic norms, Olympia is key to today's radical art—in all her unapologetic glory.