In Amedeo Modigliani’s case, it was destiny. Painting was the only path for the winsome, sickly boy whose mother once wrote, “He behaves like a spoiled child, but he does not lack intelligence. We shall have to wait and see what is inside this chrysalis. Perhaps an artist?”

That he became one of the most recognizable artists of the 20th century isn’t shocking. Now, just over a hundred years after Modigliani’s death, the Barnes Foundation unites over 50 works for a retrospective without precedent in scale, focus, and ambition.

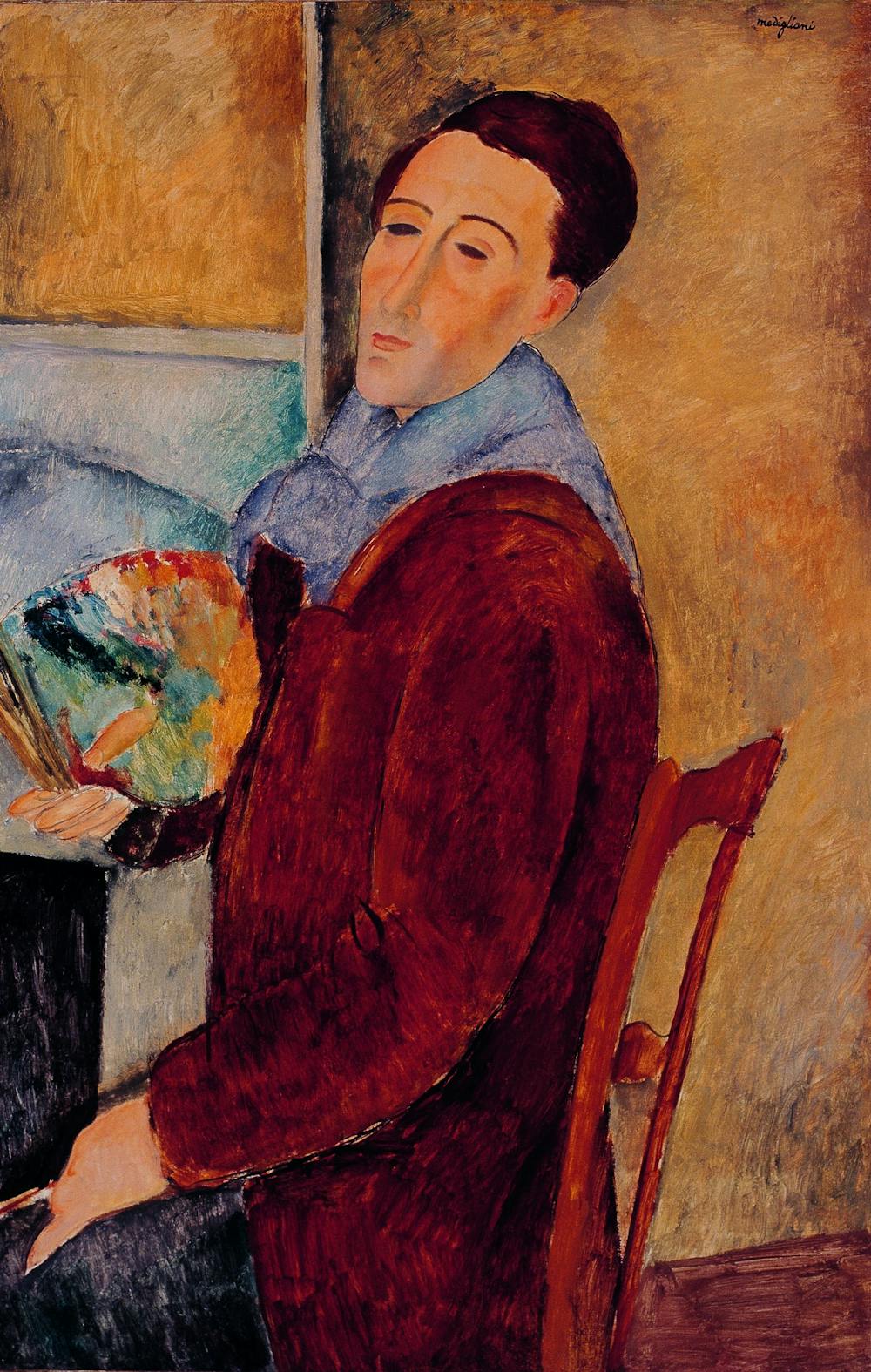

Amedeo Modigliani. Self Portrait, 1919. Museu de Arte Contemporanea da Universidade de São Paulo, Gift of Yolanda Penteado and Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho 1963.2.16 / MAC USP Collection [Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP Collection, São Paulo, Brazil]

Photo courtesy of the Barnes Foundation.

Spearheaded by Deputy Director for Collections and Exhibitions Nancy Ireson, Modigliani Up Close comes on the heels of the Tate Modern’s major 2017 retrospective. In contrast to this earlier show, the Barnes’ exhibition exceeds Ceroni’s catalogue raisonné, the most definitive compilation of Modigliani’s works. Four previously unlisted paintings are on display here in the third gallery. Sweeping in scale, the show unites works from locations as varied as Jerusalem, Dallas, Turin, and Paris.

The decision to display these objects together is hard–won, resulting from years of rigorous technical analysis. In preparation for the exhibition, an international cohort of scholars, curators, and conservationists performed X–radiography of the works. Pictures were then submitted to the Thread Count Automation Project. The process uncovered new connections between canvases from different stages of Modigliani’s career; we now have reason to believe that works made in Paris and the South of France were literally cut from the same cloth.

This diligence makes sense in light of Modigliani’s exhibition history. Perhaps more than any other celebrated artist, forgeries of his work abound. When fakes were discovered at a 2017 exhibition in Genoa, Italy, the displaying gallery was shuttered and the sponsoring foundation dissolved. Hence, precision is essential.

Yet, technical analysis always runs the risk of estranging the viewer from the work. What do fiber counts and canvas measurements have to do with why a painting compels us?

Mercifully, the Barnes’ efforts are subtle, purposeful, and targeted. They have the effect not just of bringing new works to the viewer’s attention, but of offering precious insight into Modigliani’s craft. The exhibition reveals that Modigliani often reused existing paintings, adding new layers onto previous artists’ works. Even as his circumstances changed drastically, such as when he moved from Paris to the Mediterranean, he continued to rely on his trusty dealer for supplies.

Watching the continuity between these works unfold is uniquely rewarding, while the various historical tidbits revealed throughout the exhibit lend us a new perspective on their creator. We learn, for example, that the stone for many of Modigliani’s sculptures was likely acquired illicitly, giving some credence to the myth of Modigliani the maverick. (The legend endures of the artist as an inveterate womanizer, alcoholic, and drug addict.)

Though much is gained by this focus on the works’ physical characteristics, the show falters slightly when it comes to that other, inner substratum: Modigliani’s private universe. In its understandable reluctance to dredge through Modigliani’s many muddled influences, the Barnes merely grazes the artist’s debts to history.

Modigliani was the self–appointed inheritor of a long tradition. It doesn’t take a keen observer to recognize his African influences. There are many records of his visits to the Musée d’ethnographie de Genève near the turn of the century—consistent with the budding avant–garde interest in so–called “primitive” art hailing from Africa, Oceania, and East Asia. These frequent jaunts left their mark: The planar, elongated faces common to so many of his pieces are an instant tell.

At the Barnes, this visual affinity is apparent in the limestone Head of a Woman (1912). One can argue that the drooping arch of her nose, rosebud mouth, and narrow face were all cribbed from equatorial Africa.

Amedeo Modigliani. Head (detail), 1911–12. Limestone.

Photo courtesy of the Barnes Foundation.

But in its sweeping overview of Modigliani’s creative methods, the Barnes treats these knotty contingencies—or debts, to speak frankly—like small potatoes. The omission smarts somewhat in light of the recently closed Isaac Julien show. Any institution that mans the gates of the so–called canon has special responsibility. The stakes are too great to be ignored when admission to the club can be life–changing. Occlusion, especially in the case of historically overlooked and exploited creators, is often fatal.

That said, the presentation of these sculptures at the Barnes is both novel and satisfying. We learn that trace amounts of wax were discovered on the objects, and land on this charming image: Modigliani likely used the sculptures as candle stands. A fitting use for the medium, stone is firm and definite. It can be held and played with in a way that a painting can’t. And this makes irony possible in sculpture, a special affordance of the medium.

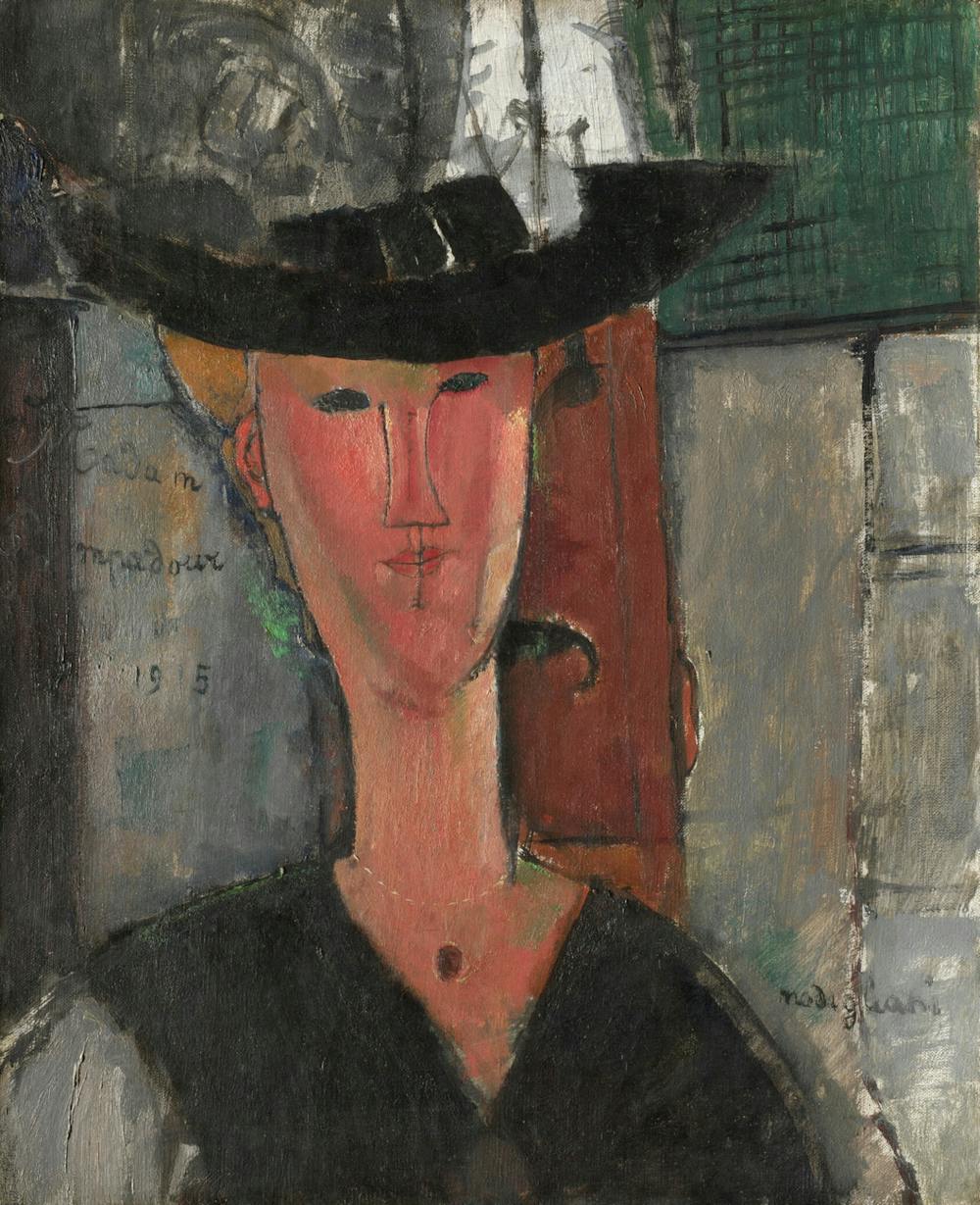

Modigliani made the peculiar choice to cast that irony aside along with the sculptural mode. When he reverted to painting by the mid–1910s, he also committed to an unwavering formal clarity. Unlike the limestone busts, which lend themselves to tactile play, these later works were destined to be looked at—and only that. Their characteristic flatness, frontal compositions, and subtle shifts in color invite a detached viewing position. And though Modigliani’s paintings exist uniquely qua paintings, there are little glyphic nods here and there. This is the case in Madam Pompadour, which bears a slight verbal inscription.

Madam Pompadour. 1915. Oil on canvas, 61.1 × 50.2 cm. 1938.217. © Art Institute of Chicago,

Joseph Winterbotham Collection.

Photo courtesy of the Barnes Foundation.

This shift in his working methods took place for health reasons (painting is less labor–intensive than sculpture), if Paul Alexandre’s account is to be trusted. But perhaps there’s another reason, that absolutes are vital for the artist who lived in extremes. And in Modigliani’s world, illness is fatal, love is redemptive, and poverty keels over into opulence. Moreover, the heights and depths of this biographical drama have a solid foundation.

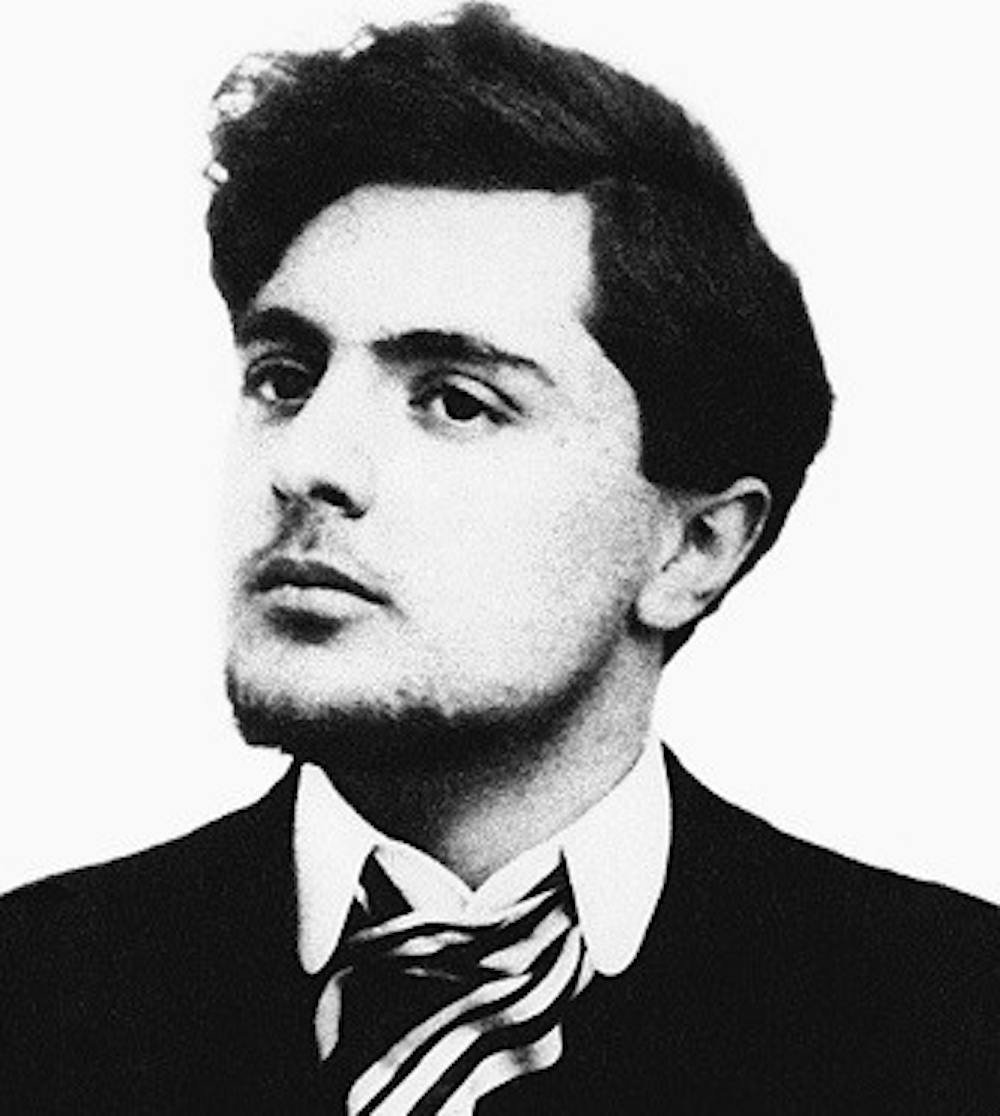

Much has been said already about Modigliani’s character—handsome, volatile, and highly gifted, the artist labored under a persona of fated creative agony. To many, his prophetic, exceptional status was visible even in his perfect features: Long, straight nose; high cheekbones; dark, haunting eyes. Modigliani was the rare artist who both exuded beauty and extracted it.

Somehow, I’ve never felt alienated by Modigliani’s women the way I have with other artists of his period. This despite the fact that his female subject is bounded by a sexual halo, and is so often contorted into offering herself. In Reclining Nude (1917), she archly peels away on a mattress. Or she caresses her own decolletage, as in Woman with Red Hair (1917). Maybe she simply bares her chest, as in Nude with a Hat (1908). And yet the artist can’t fix her—she remains impenetrable.

Among women, this dynamic is common wisdom. Cynical as it sounds, to love and be loved by men is to draw away constantly, to retreat into the imagination. We make the choice, day after day, to perform a peculiar alchemy, turning pity and boredom into affection. And somehow we’re happy in love.

Often, we find ourselves enjoying an embrace not for the texture of the lived–in moment, but for the mere fact of being embraced. Because for all the progress of the last century, few would argue that we’ve achieved true male–female sexual parity. There’s still a desiring subject and a desired object, and what this lack of reciprocity entails for women is the following routine, learned by rote:

I can’t count the times I’ve heard a girlfriend, after a glass or two, stare at the ceiling and sigh, Oh, but he’s so boring/unimpressive/mediocre. But we go on. What always redeems this or that bum is his power to discern. In the right circumstances, anyone can be led to behold the more polished dimensions of our character. And, indeed, our beauty.

Maybe Modigliani saw this, maybe not—but it’s there in the gravid blankness of his models. He’s the rare male artist who lets women look at themselves without any attempt at self–stroking artifice. At the Barnes, this comes to bear in the glorious, ethereal Jeanne Hébuterne (1919). The picture lets us finally behold ourselves as we are: inscrutable. There’s a total absence of any attempt to temper or ennoble the confusion of staring at the beloved. No smile. No eyes. She grants us nothing.

Amedeo Modigliani, Jeanne Hébuterne, 1919. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nate B. Spingold, 1956 (56.184.2) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource

But one might protest: What about those luminous, brilliant nudes? They, at least, surrender to the artist. They are comprehensible. And it must be granted that these nudes are a representational triumph of an entirely different order.

Modigliani doesn’t hurl himself on the female figure. Unlike Pierre–Auguste Renoir, whose pictures are strewn throughout the Barnes collection, this artist doesn’t inflate his subjects into formless beings. Rather than avail himself of women’s anatomy, he grants his subjects the essential quality of eroticism—exclusion.

Georges Bataille, in his comprehensive study on the topic, makes the case that eroticism rests on difference. There’s an essential discontinuity between the desiring subject and the desired object, and to overcome this gulf would be to die. The temptation to dissolve this discontinuity and cross over is the erotic impulse.

Accordingly, the bodies here are exposed and extended away from the viewer. The famous Reclining Nude (1917) recedes even as she welcomes our gaze. To borrow again from Bataille, “Eroticism … is assenting to life up to the point of death.” Here is a woman suspended between the two.

The result is painted bodies that brim with erotic charge. More than that, they tower—and judging by Modigliani’s lasting popularity, they endure like all the best–constructed wonders of the ancient world. Modigliani has captured the gulf between lover and beloved.

His is a subtractive eroticism, where beauty and temptation are found in what’s absent. Small wonder that these bodies appear carved out of a whole, muscle and bone alluded to as mere curves but never fully articulated. The truth Modigliani lays bare is that we’re attracted to the question mark: whatever is implicit in the body, what can only be coaxed out by an artist or a lover.

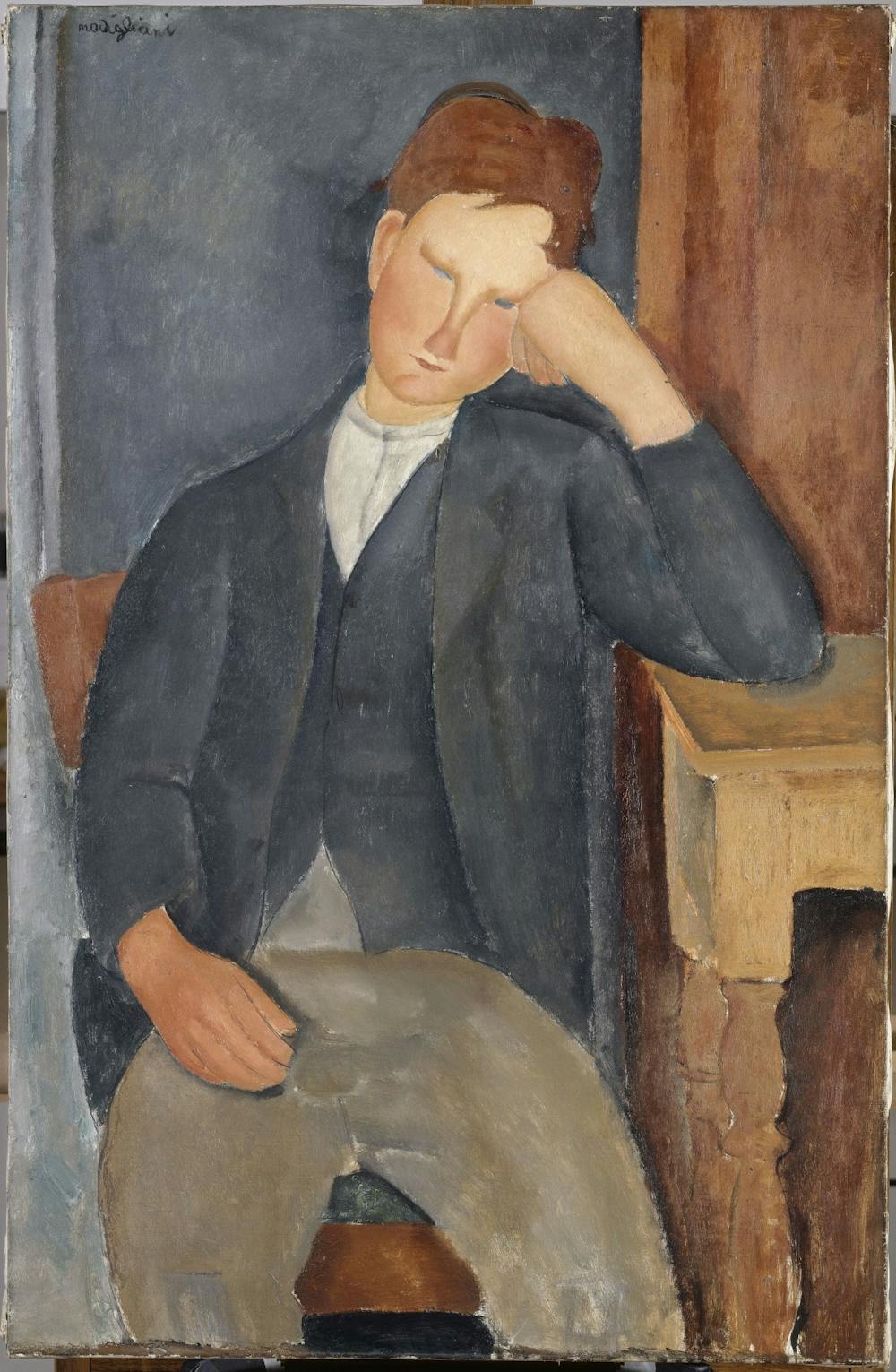

The Black Hairdo, or Young Brown Woman Seated. 1918. Oil on canvas, 92 x 60 cm. MP2017-30. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY Photo: Adrien Didierjean.

I look at these nudes, see his earnest longing, and feel a surge of guilt. My love, unlike Modigliani’s, is cowed by insecurity, fickleness, and cruelty. In front of Standing Nude (Elvira) (1918), I remember one face in particular. What it must be doing now—chewing the end of a pen, squinting at some difficult text, tumbling through a thousand brilliant thoughts. Recently, I found a note that I never sent for lack of courage:

I think of what to paint and always come back to your face. If I close my eyes and try to reconstruct it feature by feature, it’s no challenge. I can see you as clearly as if you were standing in front of me.

I never delivered the portrait I promised. But Modigliani plates that lovely, haunting face up to me now, along with a thousand others. John Berger called his work an “alphabet of love,” but that love, rendered in such firm and finite form, feels remote.

To return to the notion that women can see themselves in Modigliani, if these portraits feel like mirrors, the reflected image stings. Walking through the galleries is akin to cycling through a rolodex of hurt. Here are the ghostly faces of the mother you never call, the front–row girl you gossip about, the niece or nephew you snapped at. The saint and the sour–faced lover keep each other quiet company.

Caught between these mute, listless faces, one is tempted to hew to the cliche of Modi maudit: the damned painter who ravaged his body, his young lover, and his unborn child—and, for that matter, the subject of love for all subsequent painters, for as long as these images persist. Modigliani peeled back the horror of loving another; without even considering his tragic trajectory, these portraits are inscribed with the knowledge that the intoxication and surrender of love can so easily unravel into suffering.

One look at the angelic, impassive face of The Little Peasant (1918) stops me dead in my tracks. There’s no recourse against the figure’s judgment because there are no eyes to meet. Instead, the portrait implores and accuses and locks you in its disappointment. Like so many Modigliani works, the painting kills.

But maybe there’s another way, the way of Modi the gutter king, who made poverty sumptuous. Modigliani’s destitution is a known fact. He’s the artist who could feast on only bread and water, who could make the naked body stately. To live on simple, sparse matter, to have everything you own fit into a suitcase, means existence, down to the crumb, has become naked and frontal.

Fabric, sunlight, blood, sky, sex—in Modigliani’s visual lexicon, these terms are equal, and equally venerable. This unique visual register—crude, earthly, and devastating as it is—is apparent in his portraits of his pregnant lover, Jeanne Hébuterne. Here, he offers a way to begin life, not inside another human being, but on a canvas.

The circumstances of her death bear repeating. A century later, they remain unfathomable. The day after Modigliani died of tubercular meningitis aged 35, the heavily pregnant Jeanne threw herself out of her parents’ apartment window. She was 21.

In the years since, her estate has been notoriously guarded about the details of her brief, tragic life. There’s a grandson who doggedly refuses to cooperate with biographers, so we’re left with few relics of Hébuterne and the unborn child. The intricate circumstances of their deaths—the cold and the hunger, the father’s illness and the mother’s fatal distress—are, miraculously, made cogent here.

Modigliani Up Close’s emphasis on physicality is fitting, given that the paradox of Jeanne Hébuterne (1919) is the paradox of all representation. That child knew no existence, save what’s implied in this unintended memorial. Yet, its being is captured for all eternity. So, too, is Hébuterne’s. And here lies yet another articulation of eroticism: the longing for the sacred, the elevation of human to ghost. The real bodies denoted here are nothing but dust, but the fickle, vaporous feeling of love has been made matter. Flat, sure, on the skin of the canvas. But real matter.