Iris Brown, a founder of the gardens at Norris Square Neighborhood Project, sits at a picnic table against the backdrop of a bright–colored pergola inscribed with the word “hope” in three languages as she shares the story of how the Kensington–area urban garden came to be.

“We had nothing in this community until we started gardening,” she says.

A native of Puerto Rico, Brown moved to Norris Square, a neighborhood in West Kensington, in 1970. During her early years, she remembers Norris Square to have been a vibrant and close–knit community, where four generations of Puerto Rican residents lived. She could walk to any local business, be it the bank or the corner store, and know the owners by name.

Associate professor of city planning and urban studies Domenic Vitiello explained that Kensington was once the “textile capital” of the United States. Just a few blocks away from Norris Square, Stetson Hats had employed 5,000 people at the beginning of the mid–20th century.

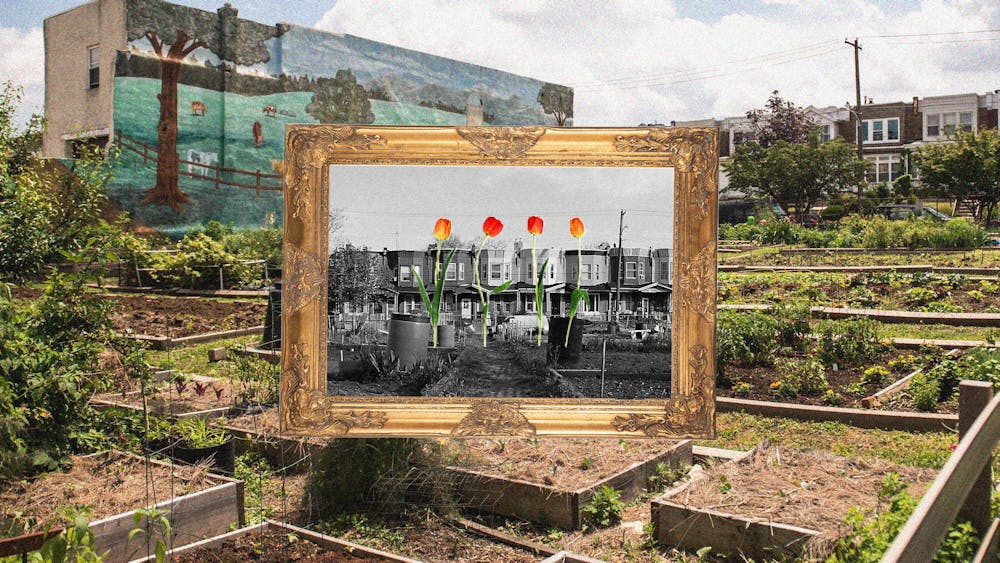

Yet, by the mid–1970s, the loss of manufacturing jobs associated with ongoing deindustrialization, combined with the arrival of drugs, hollowed out the neighborhood’s institutions. Brown remembers this period as “a nightmare.” Drugs were sold on every corner, sirens and gunshots pierced the air, people died of overdoses on the streets, and houses burnt to the ground, turning the block into a shell of what it once was.

In response, many of her neighbors moved to other parts of the United States or back to Puerto Rico, Brown explains. The banks, hospital, and other community spaces closed. As the neighborhood emptied out, vacant lots emerged that soon became sites of open–air drug markets.

In the 1980s, an anti–drug raid incarcerated about 60 members of the community who were involved with the drug trade. Brown and others had hoped this would improve the neighborhood, but their removal ultimately had the opposite effect.

The aftermath of the drug raid was “a different kind of suffering,” according to Brown. It ripped families apart, leaving some children without caregivers. There were no social workers or other forms of support offered to families impacted by the raid.

“Our community never had much, but what little we had was gone,” Brown says.

In response to the community’s struggles, Brown and a group of neighborhood women called Grupos Motivos committed themselves to providing a much–needed support system for the community. They joined forces with Natalie Kempner, a local elementary school teacher who founded NSNP as a nature center for children in 1973.

One of their first priorities was figuring out how to transform the vacant lots scattered throughout the Norris Square neighborhood into spaces that could uplift all of its inhabitants.

“What can you do in an empty lot?” Brown asks. “A garden is the only option.”

Over 45 years later, NSNP offers local youth a safe space to develop their leadership skills, build relationships, explore culture, learn about urban agriculture, and express their creativity through art.

It is this dedication to community enrichment that is at the heart of NSNP’s mission.

Approximately 40 eighth–grade and high school students currently participate in an after–school program “designed to keep them off the streets, be fun, and teach 21st–century skills,” says NSNP Director Teresa Elliott. The program offers technology, arts, and gardening education as well as homework support. Meanwhile, outdoor kitchens provide a space for cooking demonstrations. Students also participate in running a weekly farmer’s market, selling produce to the Norris Square community.

Themed gardens also celebrate Puerto Rican culture and instill heritage pride, paying homage to the community’s roots. One such garden, Las Parcelas, features a traditional Puerto Rican farmhouse, while El Batey includes a Taíno hut—providing opportunities for residents to engage with different elements of Puerto Rican history. Murals portraying Puerto Rico’s past and the women of Grupos Motivos overlook the students as they learn together.

In 2006, Brown developed Villa Africána Colobó as an exploration of the Puerto Rican African diaspora. The garden features both African and American plants and crops, while African proverbs line the fence. The cottage situated in the center, filled with an eclectic mix of masks, books, patterns, and more, is Brown’s storytelling hut, where people gather around the table to learn and exchange stories.

Brown emphasizes that the inspiration for the hut came from witnessing frequent fights over race among Puerto Rican youth. She views it as a space to instill pride and “explore the beauty that came from Africa.”

Several decades after the founding of NSNP and two and a half miles west, Tommy Joshua Caison, the founder and executive director of the North Philadelphia Peace Park, was facing a similar predicament. Debating how to fill the vacant lots surrounding the Norman Blumberg Apartments, a 499–unit housing project in the Sharswood area of North Philadelphia, Caison too believed that installing a garden would best serve the interests of the local community.

Caison’s background as a neighborhood resident, longtime activist, and educator allowed him to bring people of many backgrounds together to make his vision a reality. In 2012, the North Philly Peace Park opened its doors to the public.

“We believe ourselves to be introducing an alternative development model,” Caison says. “We felt that it was something that the whole city and even the country could learn from and benefit from.”

Sharswood was historically a hub for African American arts and culture, Caison notes. Pearl Bailey, Duke Ellington, and the Nichols Brothers performed at the Pearl Theater, a local jazz and dance venue that closed in 1971. Famous activists—including Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Cecil B. Moore—worked, spoke, and marched the district’s streets during the Civil Rights Movement. This legacy continues: Today, Sharswood is still 76.4% Black.

As well–paying job opportunities declined in North Philadelphia, crime and drug–use rates rose. Today, about 56% of residents live below the poverty line, making Sharswood one of the poorest communities in the city. The North Philly Peace Park, Ciason highlights, serves to uplift and empower this population that has traditionally been underserved and overlooked by local government.

“I started the Peace Park as both a stance against our current conditions and a continuation of the African American quest for democracy here in America,” he says.

Caison explains that the park serves as an extension of African American attempts to revolutionize the Constitution and expand the notion of citizenship beyond a white male property owner. He draws inspiration from his early experiences in the outdoors, including visits to his uncle’s farm in North Carolina and explorations of abandoned warehouses in Fairmount Park.

“Just like somebody would use paint or clay, I view soil as a medium for human rights, human creativity and community,” he says.

Similarly to NSNP, the Peace Park has also made youth engagement a pillar of its mission.

The Peace Park seeks to encourage Black pride and an understanding of Black history. Cutouts displayed in and around the garden pay homage to Black activists, artists, and teachers.

This pride extends to the park’s afrofuturist design. Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthetic that fuses science–fiction, history, and fantasy to examine the Black experience.

Caison explains that afrofuturism allows African Amercians to “reconnect to a time before enslavement or colonialism and challenge the anti–Black status quo.” Peace Park creators utilize afrofuturism to “imagine without limits,” he says.

The afrofuturist lens has been combined with sustainable building practices to create a community–designed school house, which is scheduled to be complete in fall 2023. The school house will support a “dynamic, culturally relevant” STEM education to further what youth are already learning through their involvement with the park’s gardens.

“We’re looking to produce innovators and humanitarians who can go on to solve some of the problems in the world,” he says.

Caison highlights that combating the food insecurity plaguing the North Philadelphia area has also served as the catalyst for much of work being done at the Peace Park. Before a Grocery Outlet Bargain Market opened in March 2022, Sharswood was labeled as a food desert, with the closest grocery store over a mile away.

The Peace Park seeks to combat food insecurity by teaching community members how to grow their own food effectively and sustainably. They also promote healthy consumption habits, holding a regular food distribution program to give out produce and non–perishables to people in the community.

“Food is the foundation, but it's all about a full spectrum of community programming that empowers people and extends a democratic revolution,” Caison says.

The Peace Park has also extended its efforts to address other health and wellness challenges faced by Sharswood residents. Therapists, drug and domestic violence counselors, and nutritionists are available to support neighborhood members in need.

To address the ongoing poverty crisis, the Peace Park launched a Green Wall Street program in 2020, challenging neighborhood residents to develop natural products, many of which are derived from the garden’s harvest. The Peace Park helped those who could do it form LLCs and provided a weekly market to sell their products.

“All of our focus areas stay true to our vision of reclaiming the land,” Caison says.

Skip Wiener, a native of West Philadelphia’s Haddington neighborhood, returned to the community to found Urban Tree Connection in 1989. Decades later, UTC has transformed 29 vacant lots, totaling more than 86,000 square feet of land, into a space for communal growing and gathering, sustainable food production and distribution, and multigenerational health and wellness education.

After receiving a master's degree in landscape architecture from Penn, Wiener worked as a landscape architect at John Rahenkamp Consultants. When he lost his job, he knew that he wanted to continue his vocation and saw an opportunity to use his skills to enrich the neighborhood that he grew up in.

That same year, the William Penn Foundation had taken on a project to provide after–school enrichment for students who live in high crime neighborhoods, including Haddington. Wiener got involved with the effort, engaging students in neighborhood gardening projects.

“I met some of the brightest, most competent kids living in Haddington,” Wiener says. “But their days were lacking structure. Our programs became a source of stimulation for them.”

The students brought Wiener to an abandoned lot that had become a drug hotspot. The group began to garden on it, covering the area in wood chips and plants. Wiener described the process as “very organic,” with no initial long term plan.

Wiener pointed to the Haddington block captains—residents who opt to lead cleaning and community efforts—as essential contributors to the growth of UTC. The block captains suggested neighborhood lots that could be improved through UTC, and they worked together to redirect kids involved with the drug trade and violence.

“While some people looked at UTC as a funky garden program, I saw it as a community development program,” Wiener says. “You could hire for and fund the technology of farming at any level, but you could not deal with how kids were spinning out of control, guns and drugs without a community dialogue.”

At UTC, the development of youth educational programming has created a space for community dialogue and relationship–building.

Monthly workshops teach gardening skills and act as a space for discussion about the neighborhood. Conversations are “often rooted in food, land, and environmental justice in a way that speaks to people’s daily lives,” according to Noelle Warford, who assumed the role of UTC executive director after Wiener retired in 2016.

Like the North Philly Peace Park, UTC’s programming also hopes to address many of the major concerns facing residents—including food insecurity.

In 2009, Haddington residents expressed a desire to repurpose a vacant lot being utilized as a chop shop for stolen cars to create a community farm that would generate affordable, chemical–free, and Haddington–grown food available to anyone in need. A lawyer recommended Wiener go to court and share a video describing his plans for the land and to request ownership of it.

“The judge stood up ten minutes into the video and said ‘I don't want to hear any more, it's yours. Take the piece of land,’” Wiener says.

Weiner received superfund money to remove contamination from the land and to prepare it for growing. He had no agricultural background but soon found support among the community’s older members.

“All these Black 70– and 80–year–olds came out of their houses and said, ‘You're doing it wrong, this is the way to do it,’” Wiener says. “All of a sudden, I had tapped into a southern Black farming culture that was dormant.”

In the farm’s early years, a portion of the food grown on the land was donated to community organizations and food banks. The rest was sold by residents at farm stands throughout the neighborhood at affordable prices.

When the COVID–19 pandemic hit, UTC changed their model to make all farmed produce free. In collaboration with city block captains, UTC began a door–to–door delivery service—a practice that “aligns with their goal of uplifting community leadership,” Warford says.

Through a collaborative process, UTC has provided support to the community and has innovated in the face of new challenges.

While the work of these community leaders has brought much–needed resources to underserved neighborhoods, many of their land reclamation efforts have been met with pushback.

In March 2022, renovations to the UTC memorial garden in honor of gun violence victims were completed—providing residents with a well–lit walking trail in line with their desires. A month later, right before an open house revealing the improved space, UTC got word that the garden—along with 30 to 40 other lots—was slated for redevelopment.

Warford learned that the redevelopment was part of the city’s Turn the Key initiative, which is intended to support affordable housing. The $400 million dollar plan will build up to 1,000 houses on publicly owned land. The monthly mortgage will be less than the median monthly for a two–bedroom apartment, and the Neighborhood Preservation Initiative will also be offering up to $75,000 in soft loans on the houses for first–time buyers.

Yet, Haddington residents were skeptical of the plan. They were not told about the development nor informed about the cost of the finished housing, making them feel like it wasn’t being carried out in their best interests. UTC gathered over 100 signatures of neighbors who wanted to save the gardens.

Through the petition and support of other city organizations, UTC was able to save half of their land. Still, the other half will be developed in line with the Turn the Key initiative.

“It’s very frustrating how we often get pitted against affordable housing,” Warford says. “The roots of housing and food insecurity are the same.”

The community’s concerns are not unfounded. While Turn the Key’s maximum sale price of $280,000 may be affordable when considering the median income of Philadelphia county as a whole ($105,400 for a family of four), the average annual household income in Haddington is $32,000—leaving the new development well out of reach for many locals.

As UTC continues to fight to preserve the other half of their land, Warford emphasizes that the issue has sparked conversation in the neighborhood about other forms of development that are occurring.

“We have to be able to develop a shared and collective goal towards preserving these spaces, holding decision makers accountable, and having clear demands,” Warford says. “This creates accountability so that public officials are doing things that actually improve people's daily lives and don't create more harm.”

Such challenges extend to the Kensington neighborhood as well. Around Norris Square, new homes are interspersed with older ones. NSNP has been impacted firsthand by this gentrification.

On Dec. 23, 2021, right after NSNP had closed for the holidays, developers started digging into the El Batey garden without any warning or communication with Elliott and the rest of the NSNP team. The developers destroyed the garden’s raised beds and shifted their fencing.

Elliott called the police to report trespassing. Soon after, a surveyor was brought in to review the land. With legal counsel and support from community partners, NSNP was able to reach an agreement with the developers, and they regained control of the garden.

Yet, this incident was not without loss. The developers built right in front of the butterfly mural that lined the garden, removing the garden’s access to morning sun and eliminating the view of the mural.

“[This loss] was extremely emotional for me. It certainly wasn’t in my job description,” Elliott says. “It’s like we’re starting all over with this garden.”

Although the mission of the North Philly Peace Park is now supported by the city, Caison explained that this backing was not won easily.

In 2014, after being alerted by a neighbor, Caison attended a Philadelphia Housing Authority meeting at Miller Memorial Baptist Church—just a few blocks away from the original Peace Park site—where he discovered lawyers and developers in conversation. Caison tried to introduce himself and speak to the value of the park and to push for dialogue about development. Ultimately, he says he was ignored.

Caison and others who supported the Peace Park began attending these meetings regularly, transforming them into a “lively debate.”

“We stopped being farmers and became revolutionaries,” he says.

The PHA eventually recognized the Peace Park’s resistance efforts. When the PHA surveyed the Peace Park’s land, they reached an agreement to consult the park on major decisions.

Yet, soon after, Caison received an anonymous email from a PHA employee warning him that PHA intended to run stabilization tests on the property—a clear violation of the agreement. Caison reached out to PHA to request reconsideration and received no response. Instead, he awoke one morning in winter 2014 to news that the PHA had arrived to drill.

Caison and others arrived at the park to protest, and the PHA retreated. He says that the encounter “electrified the neighborhood,” attracting the mainstream media and city hall in the process.

In the spring of 2015, the PHA fenced in the park. Caison recalls this as “extremely traumatizing.” Neighborhood kids were in tears, unable to understand what was happening to their park.

Caison mobilized a resistance and took the fence down. In response, one prominent city politician personally threatened to arrest him for trespassing and destroying city property.

“I was like an outlaw,” he says.

This period of resistance and altercations with the PHA lasted for over six months. Eventually, Caison and other Peace Park leaders decided to engage in a land trade, swapping the property for new land with guaranteed security. The Peace Park moved to their current location on 22nd and Jefferson streets, around the corner from the original location. They lost all that they had built in its first three years, including gardens and an earthship.

“It was very difficult to walk away from all that we had achieved and invested in the original park, but revolution is a process,” Caison says. “Sometimes in order to take two steps forward, you have to take one step back.”

Despite some continued challenges, the PHA and the Peace Park have forged a working relationship. Caison and the Peace Park team are in the process of expanding the park over a full city block utilizing an afrofuturist lens.

“I hope that the Peace Park will stay true to its principles while also continuing to outdo itself,” he says. “And I hope the mission will grow across Philadelphia and to new cities.”

The people who tend Philadelphia’s urban gardens are united by a willingness to take initiative and learn as they go. Like the neighborhoods in which they flourish, their progress is not always linear and the hurdles they face sometimes come from people who purport to be allies in the struggle to better their communities.

“We cannot sit and wait for somebody to give us things because they’re often the wrong things,” Brown emphasizes.

It’s unclear what the future has in store for Philadelphia’s community gardens. As property values rise citywide and neighborhoods struggle to hold onto their histories amidst ongoing gentrification, community initiatives like these gardens remain a source of collective power.