If you're a fan of Matisse, Philadelphia is the place to be this fall.

Matisse in the 1930s is the latest exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), but the story it tells begins at the Barnes Foundation. When emblematic French artist Henri Matisse visited the United States in 1930, he made a special trip to see Albert Barnes, whose personal collection contained many of his works. Barnes commissioned Matisse to paint a mural that would fill the three lunettes on the southeast wall of his main gallery. The only site–specific work in this collection at the Barnes Foundation, Matisse’s The Dance was a watershed moment in his career, ultimately pulling him out of a creative rut and ushering in a new era of style and success.

The exhibition at the PMA—in collaboration with the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris and the Musée Matisse Nice—is the first one solely dedicated to this pivotal decade in the artist’s career. Prior to the exhibition's opening to the public, the PMA was in the midst of a workers’ strike which ended with a union contract on Oct. 17. Including over 100 works ranging from paintings and sculptures to photographs, film clips, and even an illustrated book, Matisse in the 1930s opens a window to the icon’s reformulated artistic process.

The exhibition spans across several galleries, each with a different theme. We begin with a prologue titled Interiors and Odalisques: The year is 1917, and Matisse paints the south of France, illuminated by soft Mediterranean light and adorned with intricately patterned textiles. This naturalistic approach, based on the observation of light, space, and figures, dominated his work in the 1920s. But shortly thereafter he would find himself adopting a new style which departed from that precedent, finding new ways to correlate subjects with strong visual forms in experimental ways.

The next room traces the genesis of the Barnes mural from beginning to end. Its walls are covered with sketches, compositional studies, and photographs that Matisse used to map out the task ahead. Here, we begin to understand the creative process and how it manifests in the work itself. Matisse used pre–colored cut papers that his models and assistants helped him rearrange on the mural canvas to plan compositional arrangements, a process that would later inspire his famous paper cutout collages. There is a large painting at the far end of the room to demonstrate the scale of the mural—it stands nearly 11 feet tall. The section includes a film clip of Matisse at work in a rented garage in Nice, complete with his dog Raudi frolicking around.

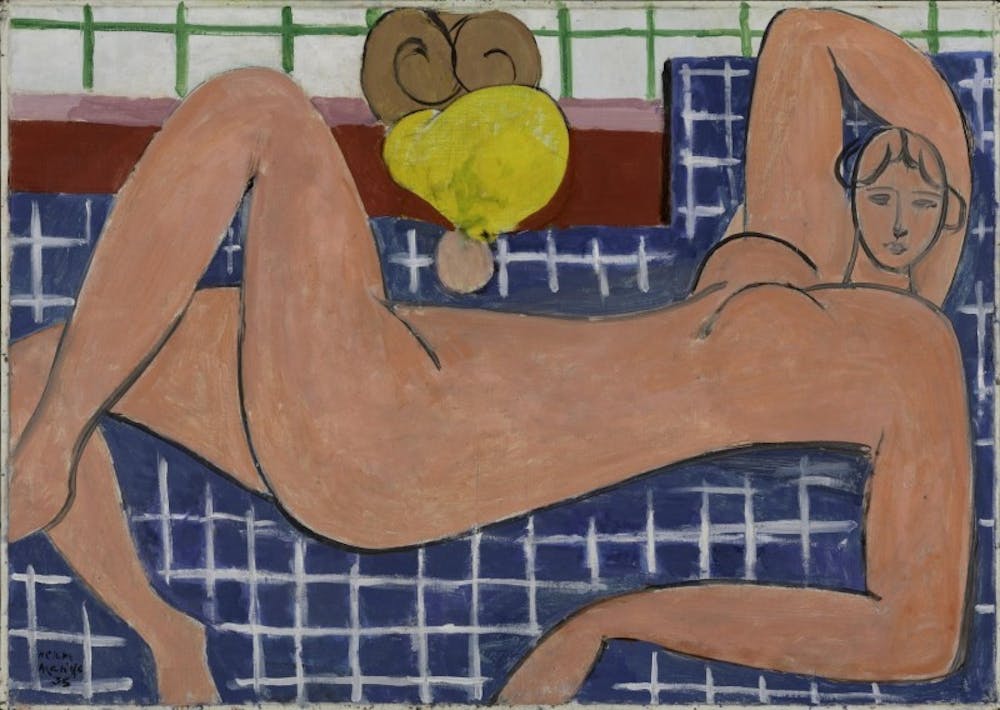

The following section highlights the female figure, anchored by Matisse's Large Reclining Nude. Continuing to depart from the naturalistic, the dreamy feeling of the mural persists in this painting. Accompanying it is a series of progress photos, taken by Matisse himself to document the changes in his work. This section also features two types of drawings: charcoal pieces that utilize a stumping eraser to create tone and record, and pure unshadowed ink drawings with no correction possible.

The gallery titled Working in the Studio continues the theme of artist and model. Here, however, Matisse’s subjects are fully clothed, dressed in modern European chic fashion. He posed the model in his studio to create works where colors and shapes were informed not only by the body, but by the design of the clothing. Woman in Blue, one of his more widely recognized paintings, is a portrait of Lydia Delectorskaya in a billowing blue skirt that she made herself at Matisse’s request. Line and design become distinct, and the rhythm between them becomes the subject of the picture. Another painting, Le Chant (The Song), was commissioned for Nelson Rockefeller’s home fireplace. The figures are animated in a musical way, and Matisse’s use of jet black paint both knits the composition together and sets off the other tones.

Henri Matisse

Woman in Blue

Oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 29 in.

© 2022 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The concept of dance surely occupies Matisse’s thoughts. Enter A Mural in Motion through an arched walkway to watch his collaboration with dance troupe Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. The choreographer of the symphonic ballet Red and Black, inspired by the mural at the Barnes, commissioned Matisse to do the set and costumes. The backdrop features three arches, just like the original lunettes, and the dancers’ leotards are dressed with subtle geometric patterns.

The exhibition ends with an epilogue—reflective on process and method—that looks back on the decade. Matisse stayed in France when World War II broke out, retreating into his studio for a mental escape. In ‘41 and ‘42, he primarily focused on drawing after facing a health crisis that left him too physically weak to paint. Ultimately, he produced 158 drawings of two subjects—female models and still lifes—organized into 17 sets, each represented by a letter. The exhibition displays two complete sets. He would begin with charcoal to learn the motif, and then go in with line drawing, doing so until his emotional investment in the subject was exhausted.

In the depths of World War II, he had the sets published in a book, referring to them as Themes and Variations. It was a meta–pedagogical exercise, revealing his method to give a look under the hood and into the mechanics of his art—and tying a neat bow on the exhibition.