Rays of light seep through the branches of the aged and leafy trees, shrouding the vendors of Clark Park Farmers’ Market and their patrons. The historic space’s paved paths connect Philly residents through produce, pottery, accessories, and art. Through rows of color and chatter, encyclopedic botanical prints catch the eye.

Amid environmental degradation and diminishing biodiversity, botanical illustrations encourage nostalgia for discovery—an untainted curiosity about nature that may feel lost today.

According to the Royal Horticultural Society, “the best botanical illustration successfully combines scientific accuracy with visual appeal.” Historically used by physicians, pharmacists, scientists, and gardeners for identification and classification, botanical illustrations precisely depict the form and features of plant life.

Wearing a cyan tie speckled with green leaves, hazel branches, and orange fruits, Dr. John Pollack, Curator of Research Services at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, carefully lays out two medical Herbals. Herbal is a term that has been adopted to refer to a whole category of texts that contain information about plants. Dr. Pollack calls to the Latin origins of his work title, caretaker, to describe his 27 years at Penn spent safekeeping historical materials and creating the conditions that make them accessible.

The botanical illustrations in the Kislak Center’s possession range from manuscripts to prints, from colored paintings to black and white illustrations, and from Western to Eastern accompanying texts. “Because people at Penn have been teaching biology and botany for decades, some of these books … have been used by students before you,” says Dr. Pollack as we sit in the MacDonald Reading Room alongside Herbal in the Tradition of Dioscorides and The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes.

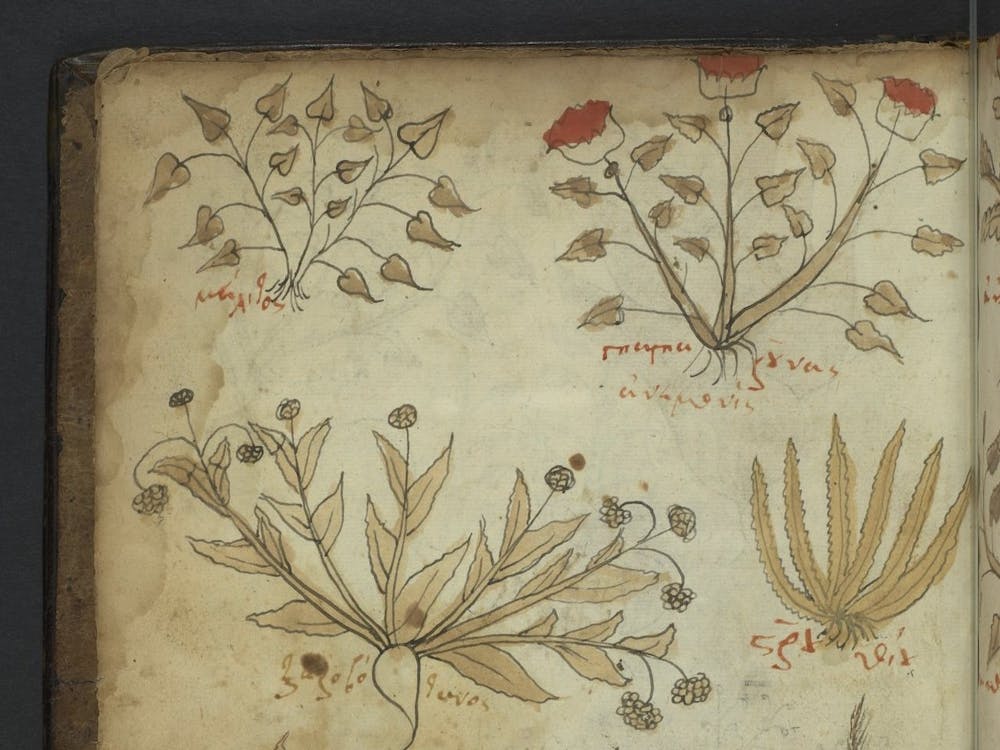

Herbal in the Tradition of Dioscorides is a Greek manuscript from the 15th century written in the Eastern Mediterranean. Bound in a 17th–century Greek binding, the pages emanate a deep, earthy fragrance and are browned at the edges, indicating extensive use. Flipping through the aged, delicate pages felt much like an interactive museum visit.

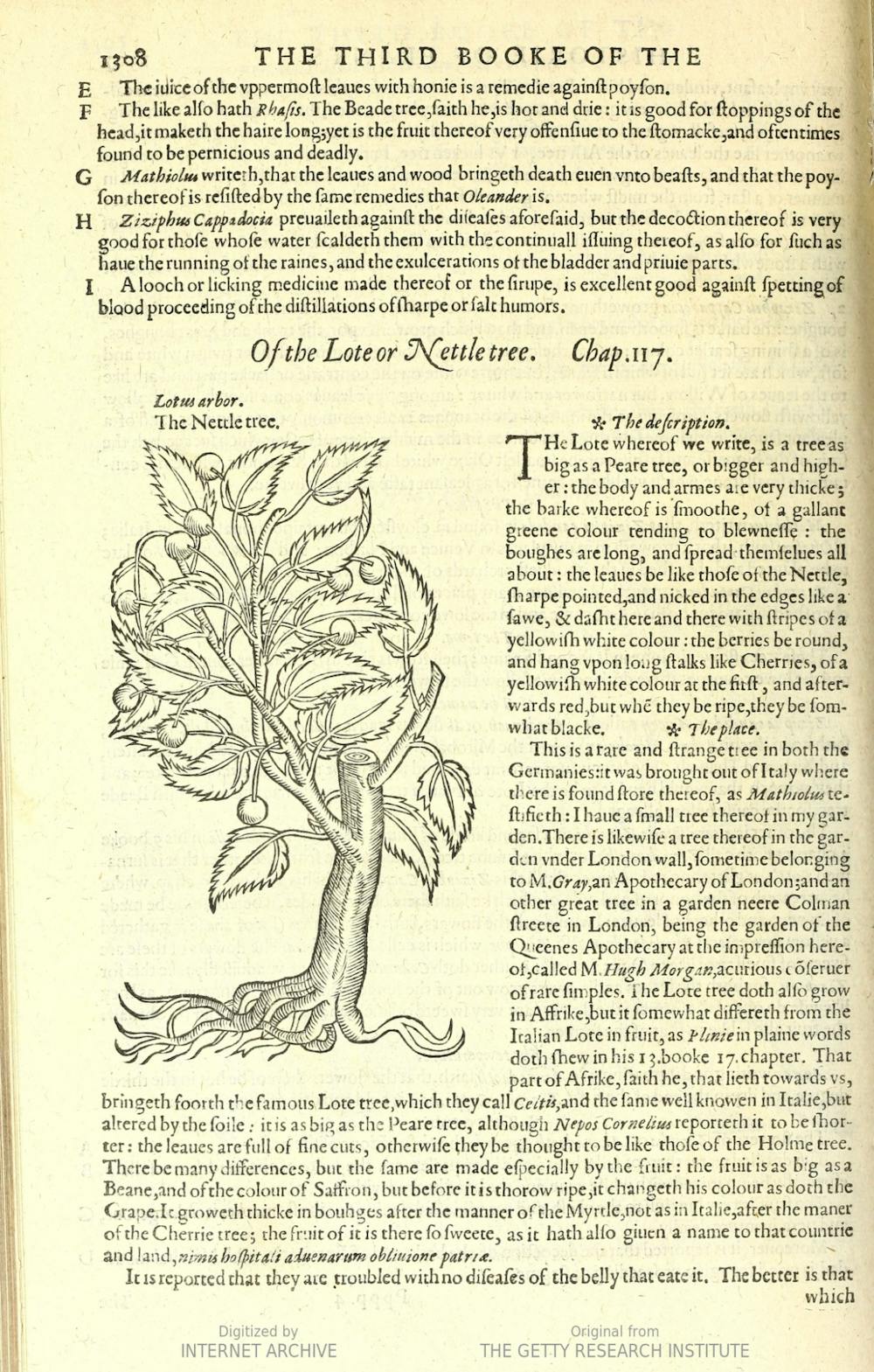

The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes is an English book printed in 1597 London, primarily authored by John Gerard. As I danced through the 1400–page book, Dr. Pollack paused to verbalize a section of the text: “the roots and seeds of grass,” he encourages me as I finish the sentence, “… are of more use in physic (medicine) than the herb, and are accounted of all writers, moderately to open obstruction and provoke urine.” Noticing how Gerard uses the word “I,” I reflect on the effect of the first–person point of view within scientific and artistic documents. “I find that the most engaging texts involve people.” In response, Dr. Pollack says, “Being personal is considered a negative but it wasn’t always that way, and there is no inherent reason that it should be that way.”

At the Clark Park Farmer's Market, I sort through the selection of prints at the Pretty Green Terrariums stall. Many shoppers share the same attraction to botanical illustration as I do. They linger by the stall, curiously inquiring about and sorting through the prints. By celebrating craftsmanship and creativity, botanical illustrations continue to hold sway, infiltrating personal spaces and decorating homes.

Back at the Kislak Center, an illustration of the nettle tree catches my eye. I realize that it matches the fruit pattern of Dr. Pollack’s tie. His attention, however, is elsewhere, as he observes the illustration’s exposed root which would be unnatural to capture via photograph. “Sometimes historical materials can teach us things that just looking forward cannot.”

The history of science cautions against the assumption that there is always progress, that there is always objectivity, says Dr. Pollack. As a forward–facing field, science rarely looks back. Botanical illustration offers a window into the potential of collaboration between science and art. It gives us a taste of the thrill of scientific discovery.