Content warning: This article contains references to anti–Asian racism and descriptions of graphic imagery, which may be disturbing and/or triggering to some readers.

This is a ghost story.

Remember eighth grade? You’re so close to being a young adult you can taste it, so you’re already trying to pretend—with mascara dolled onto eyelashes and a liquid liner flicked into a cat eye you don’t know is already out of style. You’re getting dinner with a friend at a restaurant with outdoor seating, and it’s one of those nights where the air moves electric. Just for this moment, you’ve caught the snowflake of independence on your tongue.

In the middle of learning what cavatappi is, a man approaches your table. He asks if you attend the college on the sweatshirt you’re wearing, and you (a little embarrassed) say no. He tells you that his ex–wife attended that school. You don’t know what to say to this, so you nod. He tells you you're very beautiful, that you look like his ex–wife, and asks if you’re Asian. He is looking at you like he’s expecting something, but you don’t know what to offer him.

He goes away soon, but his presence has sat down at the table. The snowflake has melted on your tongue.

I’m being arrogant. I assume you’re reading this as me, or someone like me, but maybe you remember it differently: passing a night–warm restaurant, a girl’s form catching your eye, sickening you with desire. She might remind you of someone. She might not. But you have to tell her you know what she is, and therefore that she could, one day, belong to you…

My mother says sometimes I’m determined to believe the worst of people. This brings me to another story.

One of my grandfathers (the one I do not call "haraboji") served in the Korean War. I know this because when I was 14, he helped me unpack boxes of war memorabilia in his back room. We find his discharge letter, written by a superior officer and addressed to my grandfather’s family. It comes with warnings: “LOCK YOUR DAUGHTERS IN THEIR ROOMS” and “Be especially watchful when he is in the company of women, particularly young and beautiful specimens.”

There are also boxes of projection slides. Mostly bar and club scenes, the men all white, the women all Korean. We look at them together, and my grandfather goes quiet as the women and men dip and kiss for posterity. When we finish the box, he laughs.

“Thank God that’s it,” he jokes. Or doesn’t.

Would you give him the benefit of the doubt? Would you believe the best of him?

This story could have ended differently. Let me tell you how.

You’re 18, and an adult now. You’re working a school event on campus. Last week you missed a step going down some stairs, so your foot is in a boot, meaning you cannot run.

A visitor has started asking you questions about the panel, and you are smiling because you like to smile and you like to talk to strangers, especially about things you’re knowledgeable about. It’s all going well. It’s going like it should. Until he says you're very pretty, and asks if you are Asian.

“I’m Korean,” you say back, but your heart is beating faster.

In response, he tells you he served in the Korean War. And to prove it, there is a box in his attic full of Korean ears.

You think, run, run, run.

I want to believe that the man who tells me I remind him of his wife says that because he’s lonely, and he misses his wife. I want to be honored by that, because to be a reminder of anyone’s loved one is an honor.

But that is not what this is.

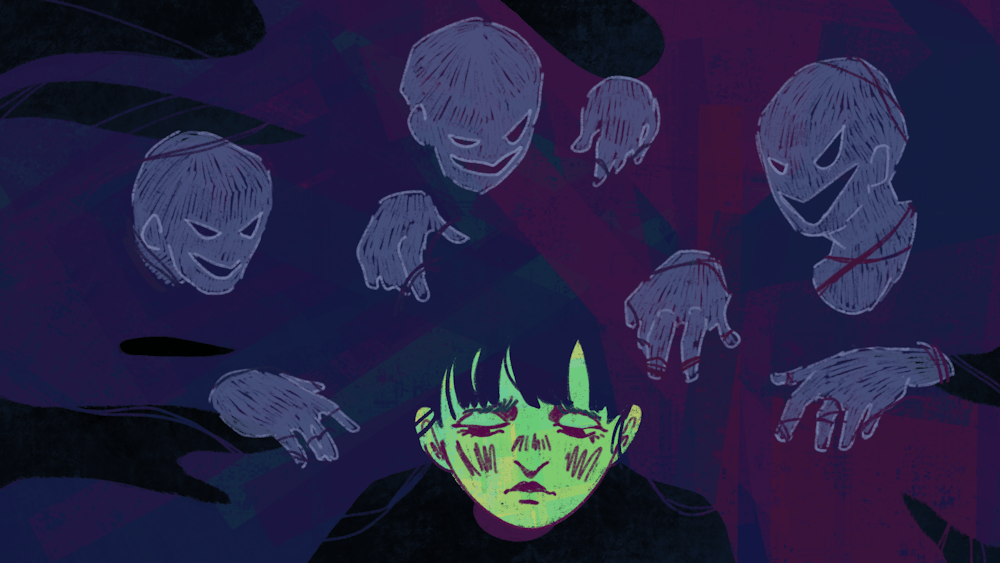

Technically, “to mourn” means to express sorrow over something you’ve lost. But you can also mourn something you have. You could call it being haunted.

I am full of ghosts, but probably not the ones you’re thinking of. I’m talking about the things you are forced to carry with you, or the things that follow no matter what. The university–attending ex–wife is a kind of ghost. The women in my grandfather’s pictures are ghosts. The box of ears, what of my mother can be found in my face, a country cut in two—all of those are ghosts, too.

Some of these I’ve chosen to bear. Others have been dumped in my lap. Some of them make me so angry I forget to breathe, and others make me despair so much I want to. None of this will change that they are there, with me, in pictures of me at bars and in the tips of my ears. Or that I will probably continue collecting them until I am a ghost myself.