Black Pegasus, 2021

ink on canvas

64 1/2” x 87 3/4”

Photo Credit: Carl Kostyál Gallery

The head of a black pegasus cast against a background teeming with foliage, its expression eerily blasé; a pair of floating, gloved hands menacingly hovering in a corner; a mountain of trash masking a cartoon tombstone captioned, simply, “Klansman.” These dystopian images belong to the world of Mark Gibson, a 2022 Guggenheim Fellow and a recent Philadelphia transplant. With their mix of jagged brushwork and vibrant Seussian details, Gibson’s illustrations present an unflinching indictment of our current political moment.

Don’t be swayed by the splashes of color and comic book figures: Gibson’s illustrations cut to the heart of our current ills. At bottom, his work critiques the devolution of political discourse into bitter, reactionary spectacle—from oily politicians to street–corner hustlers, Gibson’s pitch–black ink work takes us to task for our collective indifference to callousness.

Gibson asks: “Why, [collectively], do we usually make heroes out of callous people?” The answer lies, in part, in sheer convenience; according to Gibson, indifference to human suffering simplifies complex situations. When you remove that extra variable, difficult moral questions suddenly turn easy. But the dangers of this mode of thinking are clear.

Things escalate quickly when we become immune to callous logic. Before you know it, “you hear people say stuff about other communities, and they get to the point where they start talking about elimination of people.” Gibson observed this troubling pattern come to a head in the years of the Trump administration. He channeled his unease into a critique of political alienation that won him a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship—an honor he doesn’t take lightly.

Everyone Should Have One On Their Wall, 2021

ink on canvas

69 3/4 x 89 1/8” inches

Photo Credit: M+B Los Angeles

Gibson intends to use the fellowship to continue exploring the themes of his most recent exhibition: Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood, which premiered at M+B Los Angeles last year. That show’s purpose, as Gibson describes it, was concerned with starting a frank discussion about racial politics. The show sought to establish a benchmark about issues concerning white supremacy: “[The show] was an offering to open up a common conversation or a certain marking of terms. Like, can we all agree that the Klan is wrong? Can we all agree that certain morality tales around power and powerful individuals don't hold up?” But the conversation is only beginning. As Gibson says, “Going forward, the work is always negotiating this level of communication,” trying to form a common idiom with the viewer.

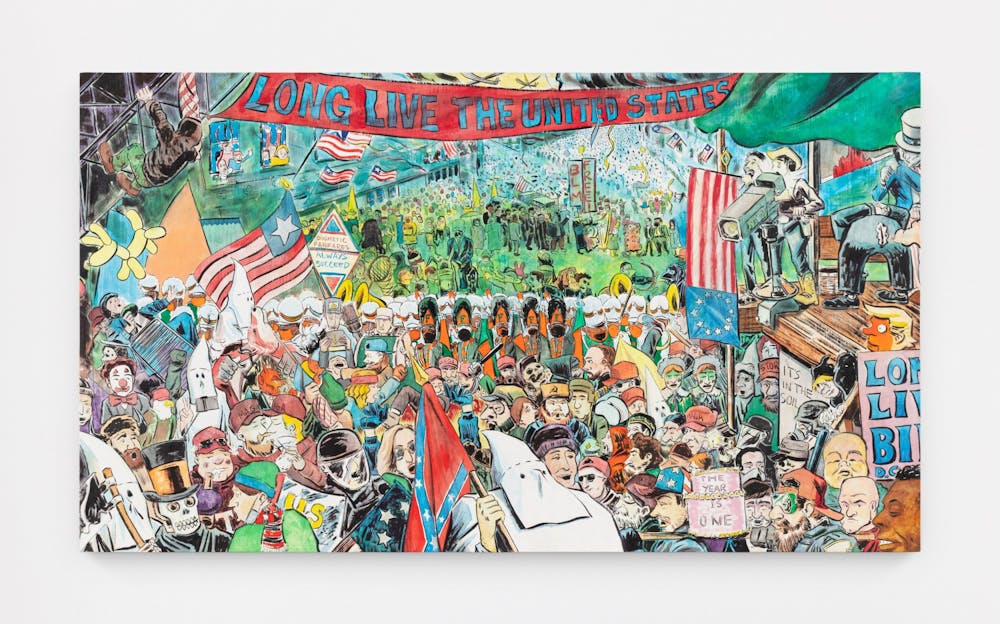

But, as timely as it may be, Gibson’s work wasn’t conceived—nor does it cease—overnight. With a new administration in office, his satire remains as scathing as ever. While many praised President Joe Biden’s election to the White House as a return to normalcy, Gibson refused to sit on his laurels. He remains just as sensible to the hollowing out of political discourse. Case in point: One of his more recent illustrations, Biden’s Entry into Washington, depicts a parade celebrating the newly elected president—but the festive crowd is punctuated by a few jarring figures: a scythe-wielding skeleton here, a Klansman there. The message is clear: same old, same old.

And yet, even as things appear to stay the same, Gibson isn’t about to lose hope and hang up his boots. If there’s a through line to all his work, it has to be his dogged commitment to compassion, his disavowal of cruelty in any form—if not to stop it in the moment, then to honor its victims. In the age of ever–shorter media bites and internet amnesia, people’s stories tend to get erased. But art, good art, can preserve them: “We are in a culture that's very quick to forget … even though we have so many more ways to actually document behavior. We have people's texts, we have emails, we have paper trails. And yet, when we're told, when we see something horrible, ‘I don't believe your lying eyes.’” Gibson’s art documents unfolding injustices not just to challenge them in the present, but for posterity.

Biden's Entry Into Washington 2021 (American Portrait as Landscape), 2021

ink on canvas

52 1/2 x 92 inches

Photo Credit: M+B Los Angeles

But if Gibson’s work is born of the current moment, the same can’t be said of all his artistic influences. He takes inspiration from sources as varied as Goya, Edo–era Japanese printmaking, and comic books. There’s no conscious calculus—Gibson is drawn to artwork almost instinctively. “It's just like, I'm gonna hunt.” He describes entering bookstores and “gravitating” toward certain works (paper prints especially) in awe of a carefully constructed color palette or well–articulated line. And while Gibson doesn’t say it outright, this instinctive method of appreciating art is another example of his willingness to go against the grain—this time, by moving beyond reductive binaries of high art and low art.

It’s a mindset that also serves him well as an educator. Besides working as a practicing artist, Gibson teaches at Temple University. His educational approach has been molded by his own experience at the rigorous Cooper Union, and he actively practices openness with his students. He sees promise in unlikely places, always remaining hopeful that “the work is already there [within the artist]. And I'm just not there yet. There's always that possibility.”