Nate Garcia lives by a simple creed: Make comics, and don’t give a fuck.

I’m sitting on the shredded hardwood floor of his West Philadelphia apartment, trying to take in the flashes of color and the sound of art utensils hitting the ground as they fall haphazardly from his desk. Nate lounges a few feet away in a low rolly chair at a wide, slanted desk, littered with hundreds of pages of sketches, notes, and inked strips. He is unassuming—face framed with thick, black glasses and shaggy brown hair, and he speaks in a low, lazy tone, like he’s discovering his backstory as he puts it into words.

His work, however, is anything but unnoticeable. Vibrant illustrations spill over the top of his workspace, original pages from his zines hang precariously from a bulletin board, and copies of his latest book line the wall in his makeshift bedroom–studio.

Nate is a 19–year–old Puerto Rican artist, adult comic sensation, guitarist in the underground Philly band scene, and “obese, probably, according to doctors.” He tells snappy, colorful stories inspired by his own life and imprints them on the page, from awkward dinners, to cold–blooded murder, to pierogi sex. “Comics is about paper. It’s about reading in your brain,” he tells me.

Nate grew up in Allentown, Pa., reading graphic novels like Bone (really anything except superhero comics). His first–grade teacher thrilled her class with stories of her roommates, cat, and ex–boyfriends, which felt like the stuff of comics Nate wanted to be reading. She tucked booklets of stapled computer paper into his folder to take home, and he brought back illustrated moments from her life—her cat even got a spin–off series.

“All these kids were confused as fuck, but I would just make zines about each story,” Nate says. “She still has them all, I’m too afraid to ask for them back.”

Nate always knew he wanted to make comics full–time, but he didn’t have the opportunity until the pandemic hit. Early in 2020, he was working at a cash–only hot dog place in his hometown for scraps, serving a never–ending stream of “old people … coming up giving me their dirty pennies for a hot dog.” After a few untenable months, he quit. Nate’s mom has multiple sclerosis, and he wasn’t about to risk exposing her to COVID–19. He made more money on unemployment, anyway.

Nate moved to West Philly later that year to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts but quickly dropped out (“I actually unenrolled before school this semester started, but it does sound cooler to say dropped out,” Nate quips). He remembers totaling up the cost of attendance and deciding that he was better off pursuing art on his own. Now, he spends long days as a caricature artist at the Philadelphia Zoo and nights hunched over his drawing desk or playing shows with his band, Attack Dog, whose music is “really loud, dirty, and kinda fun.”

Nate says the Zoo is a fun topic. “The people come, and they say, ‘Don’t draw me fat.’ I say, ‘Okay,’” he explains. “I draw them, not fat. They say, ‘It doesn’t look like me.’ I say, ‘That’s because you’re a fat bitch.’”

He breaks off, chuckling. No doubt, this story will end up in the pages of a zine if it hasn’t already.

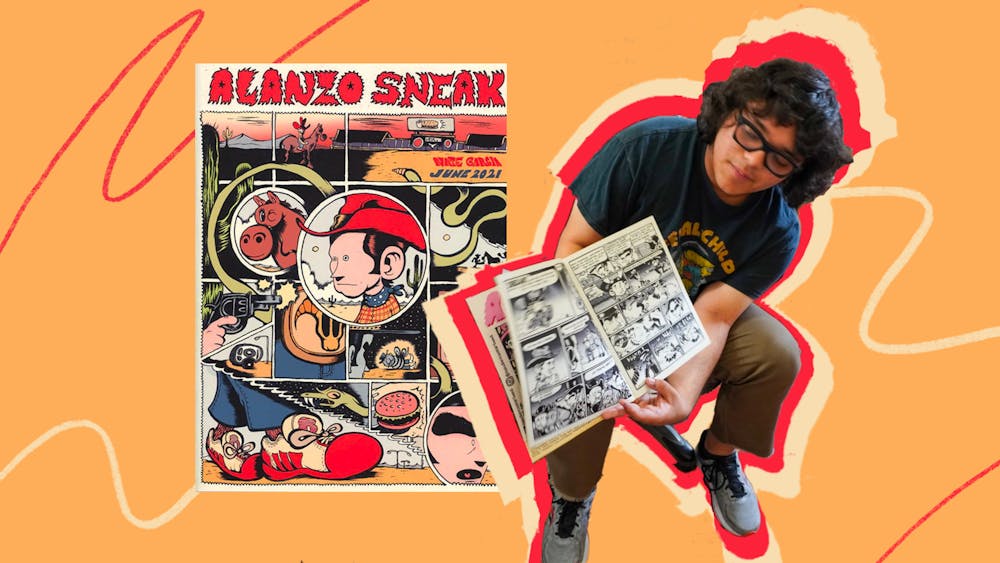

Pulling the bright volume from his spinning rack of comics, Nate shows me his latest book, the chaotic masterpiece Muscle Horse, which features Alanzo Sneak, a profane cowboy who wears sneakers instead of cowboy boots.

Nate does everything himself. He starts with a sketch, pulled from the growing list of ideas on scraps of loose–leaf paper tucked inside his notebook. He does one pass to make the strip funnier, then outlines with cheap pens. “I’ll never in my life draw on a fucking iPad,” Nate says. “I just use disposable pens—I kill the Earth every day.”

Nate draws a page per day. He flips over some sketches on his desk, revealing lopsided columns of writing scribbled in dark ink. “I use the back of every page as a diary because I can never keep a diary,” he explains.

The writing on the other side of the page is his, as well. Nate hand–letters each of his stories, although he says most artists just make a font of their handwriting. “I can never use a font in my comics. I would rather die,” Nate opines. “That’s the human touch.” When a publisher reached out to sell his work in France, Nate wrote the whole zine again in French. He’s smartened up since then—artists rarely do their own lettering for works sold in other countries at risk of fumbling the translation—but for French and English, “I just did the whole thing myself like a fucking psycho.”

After inking, Nate colors the pages in Photoshop. Once he’s drawn and colored a full volume, he has a friend put together a PDF of the final zine. “I don’t know how to make a fucking PDF, I need to learn,” he adds. Nate has always self–published, but he used to put the zines together himself, spending hours stapling the final products, before he connected with printers who sped up his process.

“It’s just stapled paper. That’s my favorite thing,” Nate says, running his hand over the seam.

A few years ago, Nate sold maybe 20 copies of his work to friends and family. Now, he’s shipping out hundreds to indie comic stores across the country, and his work is sold in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The reason? Instagram, a fact Nate both detests and reserves a begrudging admiration for.

He started posting finished comics on his Instagram, @nategarciascartoons, in April or May of 2021. Before then, he put up sketches and occasional promotional materials, but “nobody wants to see that.” Since switching to full–color series, his popularity has skyrocketed—Nate has over 7,000 followers.

“Instagram is very much a part of how I pay my rent, which is very fucked,” he remarks.

Nate posts webcomics in a format he calls “swipe comics,” sets of ten frames of illustrations. He’s not the biggest fan of Instagram—he much prefers paper media—but he enjoys when commenters theorize about the narrative arc of his work and character relationships in real time.

Gesturing to his desk, Nate shows me an installment of his current webcomic, "Gecko," in which Alanzo Sneak accidentally steps on a gecko and kills it, then dines at a restaurant owned by geckos. I ask him what inspired his latest stroke of creative genius.

“My sister had a gecko and she fucking killed it with her foot,” Nate says, breaking into a grin. “She was like, ‘This is the only thing that made me feel like I could be a mom,’ then she stood up from the couch and 'crunch.' That motherfucker died so quick.”

He adds that the gecko vet told them that the gecko was actually going to die anyway because it was malnourished, and that his sister “goes through these pets like underwear.” Nate is magnetic, and the story is edgy and twisted—I can’t stop listening.

Riding his newfound internet stardom—in–part due to the popularity of Muscle Horse, which started as a webcomic—Nate went on a tour of indie comic stores across the Northeast earlier this year. “I emailed a shit ton of shops, thinking that maybe one would say yes,” Nate says. “I didn’t realize that these shops want to have events.”

He took off work from the Zoo and rode Greyhound buses to Columbus, Ohio, as well as Hudson, New York City, and Buffalo in New York. The tour leveled up Nate’s career and served as an opportunity to connect with other indie comic artists, which are few and far between. “Everybody knows everybody,” Nate explains. “Comics is so overpowered by mainstream comics like Marvel and DC, but [small artists] care about the art form, not just trying to make movies.”

At each stop on his tour, Nate projected a scene from Muscle Horse for a reading, then signed copies of his work for tasteful customers. “It’s basically like five minutes of me moaning into a microphone with a PowerPoint presentation,” he says. “It’s really fun.”

Back in Philly, amid the mold, rodents, and water damage of his creaky apartment, Nate reflects on the corner of the city that’s allowed him to pursue this incomprehensible existence. “I’m madly in love with this place,” he says. “A lot of stuff that happened to me here ends up in a comic, and it’s only stuff that can happen here.”

I ask how he can continue creating at breakneck speed—especially in the highly scrutinized environment of social media. He lapses into silence for a moment. Then: It takes recognizing that “nobody gives a fuck about you, because no one should give a fuck about you except yourself.”

When he walks me down three flights of stairs to the exit of his building, showing me how the banister shakes to the touch, I review my notes: Nate is weird and obnoxiously talented and says “fuck” a lot. He has awkward meals at places where fries already come on the side, hates the creative medium that pays his rent, and loves the touch of fresh paper. He tells stories masterfully and effortlessly.

“It’s out of love, it’s out of obsession, and I have this obligation to do it for myself,” Nate says firmly. And I realize that he gives more fucks than anyone else in the world.