On a brisk morning in February 2022, Michael Cogbill was mounting a campaign. The 32–year–old union organizer knocked on hundreds of doors in North Philly to collect signatures that would secure his spot on the ballot for Pennsylvania’s 3rd Congressional District in the May primary. In Philly’s unpredictable winter weather, the task proved easier said than done, but conversations with eager voters kept Cogbill hopeful.

While most well–funded campaigns rely on a network of volunteers to find names for their petitions, Cogbill took up the task himself—splitting some forms with his Committee Chair Hasan Tippett, who is also his barber. Over the next month, the pair collected about 2,000 signatures to establish Cogbill’s candidacy, more than enough to put him in the running.

The campaign soon swelled to a loyal cohort of volunteers, including an intern and some of Cogbill’s former classmates. They officially opened an office on the first day they qualified for the primary and began hosting events at A King’s Cafe, a local eatery owned by old friends.

Despite his efforts, in late March, Cogbill found himself going toe–to–toe against a formidable election lawyer in the Office of the Philadelphia City Commissioners. A rival campaign had challenged hundreds of the signatures on his petition, and Cogbill, representing himself, spent two days refuting each claim to maintain his position on the ballot. The opposing campaign ultimately withdrew their challenge a few days after facing defeat—but Cogbill’s legal triumph is just a small piece of the arduous journey to getting his name on the ballot.

When we meet at the Starbucks at 34th and Walnut, Cogbill explains that it’s been a long week. A few days prior, he successfully defended his spot on the ballot—but his work had just begun. As we take a seat under a speaker blasting elevator music, Cogbill gingerly unwraps his pastry and launches into his story. It’s not “his story,” in a political sense—it’s his life, a series of events that happened to him from his upbringing to his campaign and how he worked to change his circumstances.

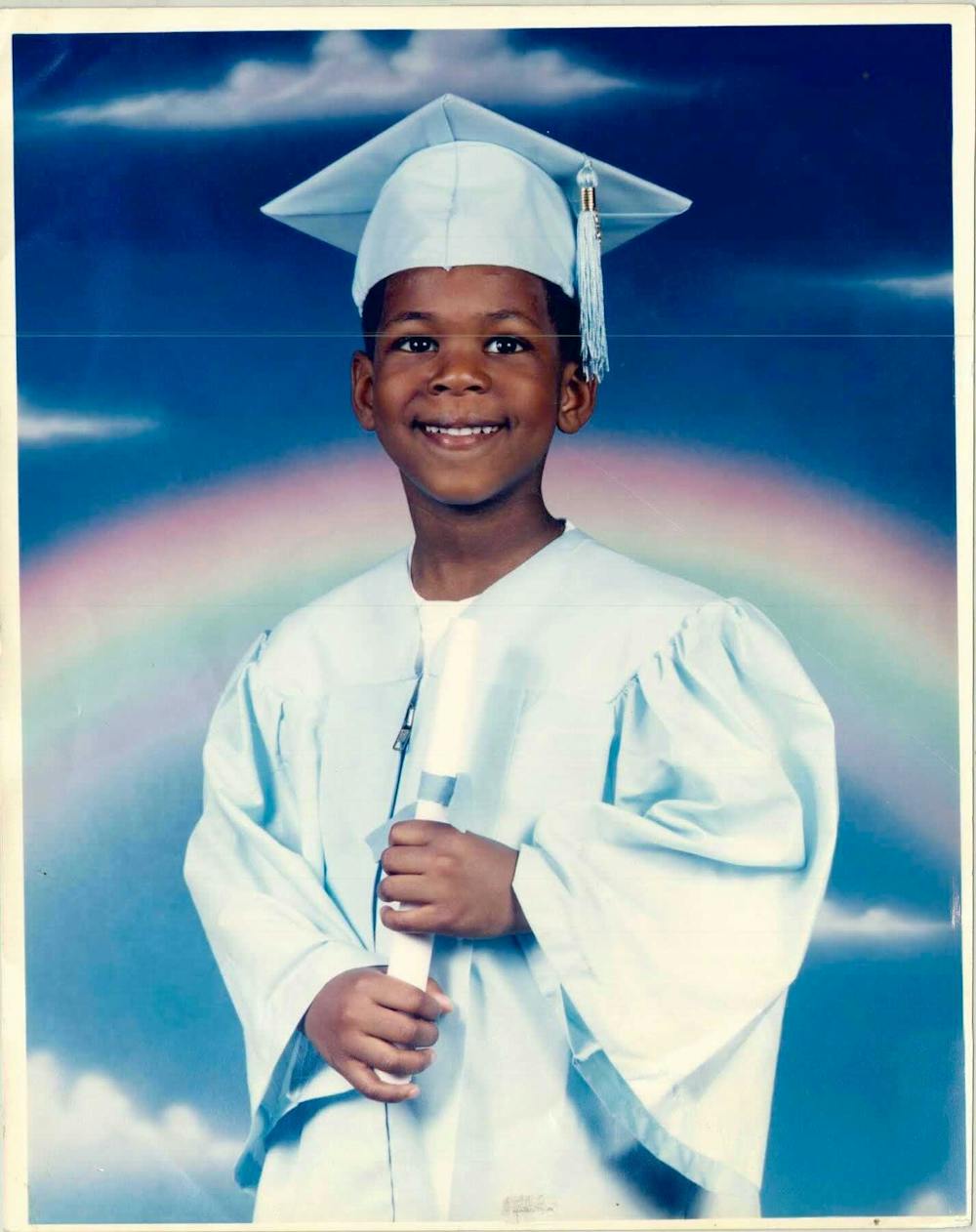

Cogbill grew up in North Philly, raised by a single mother (who he still calls every day). She had a union job driving a bus for SEPTA and made $25 an hour, which was enough to put Cogbill through “decent schools and summer camps.” Although his experience may be foreign to the average Penn student, it’s not uncommon in neighborhoods like his, some of which are only a few blocks from campus.

“I don’t think I have a sad story,” he says matter–of–factly. “I grew up in a single–parent household, but so many kids in North Philly grew up in zero–parent households.”

While his mother raised him, Cogbill’s aunt, Philadelphia City Councilmember Cindy Bass, nurtured his love for community service and social impact. He recalls the first movie she showed him: the 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning, which chronicles New York’s bustling ballroom subculture.

“She sat me down and told me, ‘You’ll never have it harder than a woman,’” Cogbill says.

Bass played an instrumental role in exposing Cogbill to Philly politics, but he insists that he’s never used her position for his personal gain.

“I've wanted to be on my own so that I'm not indebted to a system or to a machine in which I'll compromise my policymaking,” Cogbill explains. He doesn’t take any favors so that he doesn’t have to repay them later in a way that would betray his community.

However, no lesson in Bass’ advocacy playbook could have prepared Cogbill for running for congressional office—or the ballot challenge he would face in the process.

Pennsylvania’s 3rd District—which includes West Philly, Center City, and parts of North Philly—is the most Democratic district in the country, according to its Partisan Voting Index, and most of its residents are Black. Rep. Dwight Evans (D–Philadelphia) has represented the district in the U.S. House of Representatives since congressional redistricting in 2018.

Evans has held political office for the past 40 years—first as a Pennsylvania State Representative, then as a Congressman. He is a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, but his critics, and some primary opponents, say that the moderate Democrat is not doing enough to deliver for Philadelphians. Cogbill and other congressional hopefuls are pushing for sweeping environmental, housing, and labor reform.

The process of running for office, according to Penn Political Science professor Marc Meredith, begins with potential candidates collecting signatures from registered voters in the district they hope to represent. Candidates aspiring for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in the 2022 midterms needed to have collected at least 1,000 signatures by March 15.

Meredith explains that this year is unique because it took longer than anticipated for officials to finalize the congressional redistricting maps. As a result, the timeline to collect signatures was significantly shorter than usual, which made it “harder for everyone, but specifically harder for candidates with less resources.”

Collecting signatures is a mechanism used to determine if there is enough interest around a candidate before they are officially listed on the ballot, according to Meredith. But, he says, there is also a question about whether or not this is a barrier to having more open elections.

“There is this trade–off between wanting to give equitable access to everyone who wants to run for office and letting them be on the ballot,” says Meredith. “If you get too many candidates, the process of trying to select which candidate to vote for can become really challenging.”

By March 15, 2022, four candidates turned in their necessary paperwork: incumbent Dwight Evans, Alexandra Hunt, Melvin Prince Johnakin, and Michael Cogbill.

With no Republican candidates filing to run for the election this year, the primary on May 17 will determine who will represent nearly 800,000 people for the next two years and wield a key voice for working–class Philadelphians.

Cogbill’s path to the primary wasn’t an easy one—he lacks the finances, education, and campaign infrastructure that his competitors have. Nonetheless, Cogbill’s lived experiences with working–class issues inform his policy positions and discerning eye for advocacy.

After high school, Cogbill attended Lincoln University, a public college in southern Pennsylvania and the first degree–granting HBCU in the country. Cogbill had intended to study astronomy, but he was restrained by his admitted lack of physics knowledge and the university’s deteriorating facilities—another mark on the history of underfunded HBCUs. Its high–powered telescope was not functioning, so instead, he studied political science.

Throughout college, Cogbill took up odd jobs. His first was at the Philly nightclub and gay bar 12th Air Command, where he sipped soda and played on his Game Boy while he worked the door. Part–time gigs at Bloomingdale's, Macy’s, Whole Foods, Target, and as a lawn–keeper for former 3rd district Congressmember Chaka Fattah followed.

“It’s normalized to work, like, 1,000 jobs,” he says. “I’ve never been known to not be working.”

Cogbill never graduated from Lincoln. After taking a gap semester that became permanent, he joined the workforce full time and continued his education when he had the time and means. “I tried to study at every school in Philadelphia,” Cogbill tells me. He took classes at Penn, Temple, and the Community College of Philadelphia, but never toward a degree. “I wanted to take whatever course I was interested in,” Cogbill says. “Create my own curriculum.”

His hodgepodge college experience allowed him to observe educational inequities up close—the differences manifested in every corner of the classroom. Cogbill remarks that kids at Penn take notes with their laptops and iPads, while students at his HBCU still use notebooks and notepads.

“The education apartheid in our communities, the asbestos and lead in the schools, is really a microaggression against Black and brown people,” Cogbill says.

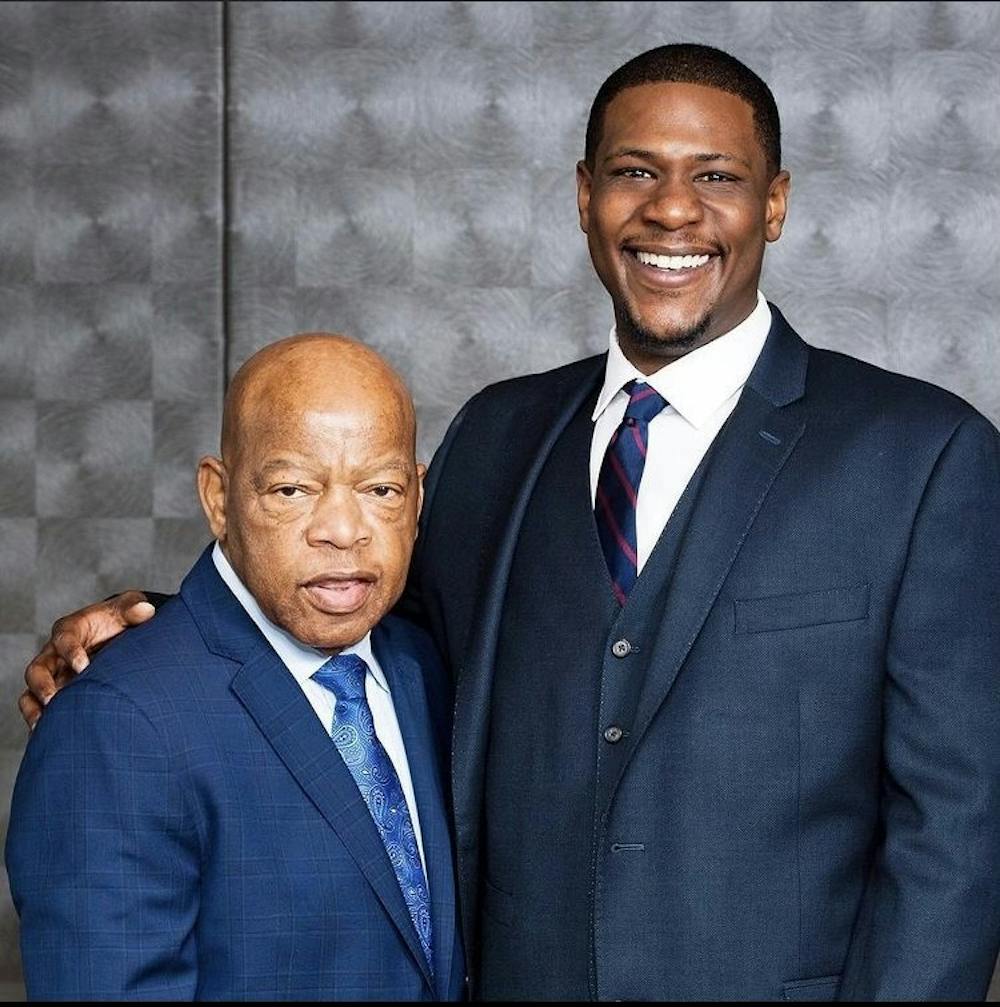

Over the decade after leaving Lincoln, Cogbill held an impressive arsenal of progressive organizing positions. He served on a handful of statewide and local Democratic campaigns, served as an intern for community service projects like Mural Arts Philadelphia, and worked at advocacy organizations like CeaseFirePA.

Most recently, Cogbill served simultaneously as the Pennsylvania state coordinator for Civic Engagement of the NAACP and as the first Black Political Director of the Philadelphia Council AFL–CIO, a coalition of over 100 local labor unions. This proved a delicate balance.

In February 2022, Cogbill left the AFL–CIO to forge a new path: running to represent Pennsylvania’s 3rd District in Washington. The departure had been on his mind for some time. He worked unpaid for the AFL–CIO for a year during the 2020 presidential election—relying on unemployment to pay his bills—and developed sciatica in his back after long days driving around Philadelphia to turn out voters ("I didn't have an office—my car became my office," Cogbill says). While he’s grateful for the impact he’s had in Philly’s organizing scene, Cogbill explains that he frequently faced blatant racism in white–dominated political environments.

“That’s white politics and Black politics in one city,” Cogbill says, referring to the disconnect between his work at the white–dominated AFL–CIO and the Black political refuge of the NAACP.

That’s why he chose to run for Congress in the first place—Cogbill wants to upend the structural inequities that impact his community.

But his place in the race was almost taken before it had even begun. When one of his primary opponents, Alexandra Hunt, filed an objection to hundreds of Cogbill’s petition signatures, he had to fight to keep his spot on the ballot.

Hunt is a public health researcher and unabashed progressive who has gained a following from her campaign’s robust social media presence. Although Hunt hails from upstate New York, she holds degrees from both Drexel and Temple universities and has resided in Philly for a few years. She champions progressive policies and aims to provoke—her slogan “Elect Hoes” references her stint as a stripper in college and appeals to a new wave of leftists, most of whom are white and degree–holding, like her. Her tagged photos on Instagram are dominated by white individuals posing in her merch in far–off locations: Denver, Chicago, Washington. They reflect her campaign’s focus on nationwide progressive issues as opposed to the 3rd District’s community–specific concerns.

The challenge capitalizes on a discrepancy of financial resources between the candidates. Hunt's and Evans’ campaigns, which have both raised hundreds of thousands of dollars, can pay staff to collect signatures and afford lawyers to challenge petitions. Cogbill, who has raised a few thousand dollars since declaring his campaign in February of this year, was left to defend himself against Hunt's lawyer in elections court.

In the process of reporting this story, Street spoke with Cogbill himself, a member of his campaign, and elections lawyer Larry Otter, who also functions as Alexandra Hunt’s campaign counsel. We obtained statements from Hunt and a representative of Dwight Evans’ campaign. Street also reached out to Melvin Prince Johnakin, who has since withdrawn from the race. Finally, we analyzed public records such as candidates’ affidavits, signature lists, and court documents to verify their statements.

Larry Otter replies to our email in a few sentences littered with haphazard capitalization. He’s the lawyer who argued against Cogbill’s petition in Pennsylvania’s election court, a microcelebrity among Philadelphia–based elections attorneys.

Otter answers each question about the process of filing an objection to a candidate’s petition in great detail, interspersing anecdotes from his years of experience running for office and representing candidates.

“The main thing I tell candidates is please come in [with] at least double or triple the number [of signatures] you are required,” Otter says. “Otherwise, especially in a Philadelphia State Representatives race, you're guaranteed to be challenged.”

Otter has been involved with election law for over 30 years. He remarks that he is “considered one of the best guys in the state.” In a post–call voicemail, he emphasizes that while he is a registered Democrat, he has represented Republicans, Independents, members of the Socialists Workers Party, and Green Party candidates in the past.

He explains that it is common for candidates to file objections when their opponents are close to the minimum signature cutoff—with the goal of knocking them out and limiting the number of competitors in the primary.

Otter describes the process of filing an objection, first noting that the most common method is a line–by–line challenge of specific signatures on a candidate’s petition. He also makes it clear that these challenges are not part of a larger conspiracy.

“A lot of people ask, ‘Oh! Is this fraud?’” Otter says. “No. They are just simple mistakes.”

Some of the most common errors in a petition, he explains, are signers not being registered voters, moving to a new address but not changing their voter registration information, or filling out their personal information incorrectly.

In a classic Otter aside, he reminisces about the MLB star signatures of old, when Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig perfectly penned their names on a spherical surface. Now, he says, baseball players just don’t sign their names like they used to, and neither do congressional district residents adding their names to a candidate’s petition.

“Scribbles happen with a clipboard in the middle of February when it's freezing outside the Wawa,” Otter says.

Individuals must submit their objections to Pennsylvania courts by March 25. Both Cogbill and Johnakin received challenges filed under the names Michael E. Kennedy and Samuel S. Whitely—names that almost perfectly match those of two individuals who collected signatures for Hunt’s campaign.

Those individuals, Michael E. Kennedy and Samuel Whiteley, provided their addresses on Hunt’s petition—and they live just a few blocks from her listed home address. Despite the potential misspelling on the court document of Whitely's name, it’s certainly plausible Hunt would ask two of her volunteers to challenge Cogbill’s candidacy on her behalf.

Many candidates may hire an election lawyer at this point to do the “tedious” work of analyzing an opponent’s petition closely. When asked who hired him to challenge Cogbill, Otter quips, “That, as they say in the trade, is none of your effin' business.”

Emails to Hunt’s campaign mailing list suggest otherwise. In two separate emails sent this spring, the latter of the two entitled “Don’t mess with the Otter,” Otter is identified as “Lawrence M. Otter, Esquire,” and “counsel for the Hunt campaign.”

Hunt provided context to her challenge of Cogbill’s petition in an emailed statement, saying, “There are some people who wake up one morning and spontaneously decide to jump into races or are planted there to undermine a competitive challenger. We were concerned that Michael didn't actually have the signatures he needed to make the ballot and didn't want our campaign's hard work to be undermined.”

A quick Google search reveals that Cogbill has a long history of labor and racial justice organizing within the city, suggesting that his campaign is a legitimate endeavor. Johnakin, on the other hand, sought the GOP nomination to run against Evans in 2020, but he was unable to collect enough signatures—blaming complications with the COVID–19 pandemic. He previously told Philly Leader that he has “always been a Republican.”

Johnakin did not respond to a request for comment, but he withdrew his candidacy after being removed from the ballot earlier this month.

Hunt’s challenge to Cogbill comes out of left field—she speaks extensively on social media about defending her own campaign from legal attacks. In a tweet on March 12, she writes, “We know our opponent will continue to fight the legitimacy of our campaign. Their legal team will comb through our list, looking for technicalities to throw out!”

In a handful of posts and emails from the past few months, Hunt paints a picture of her campaign under attack, referencing an unnamed “opponent” out to undermine her candidacy. In her emailed statement, she references that her campaign has received “multiple threats that they would be kept off the ballot,” but she never received a challenge to her petition.

A statement from Evans’ campaign asserted that “This campaign has made no legal challenges of the 3 primary opponents and has instead focused on communicating to the voters about the Congressman’s record and the resources he has brought back to the 3rd Congressional District.”

Prior to the court date, Otter explains that the challenger must meet with the candidate’s committee to talk through each challenged signature and come to an agreement.

Cogbill and Otter met on March 26 and 27, spending over 16 hours analyzing the challenged lines in Cogbill’s petition. After two days of back and forth, they reached a point where there were not enough unresolved challenged signatures to continue the process. Otter says that while Cobgill was annoyed at times—as all candidates are when they see their work disputed—he makes it clear that “it never got that contentious.”

Otter recounts an instance in 2006 when representing a Green Party candidate, a fistfight broke out in Harrisburg over the U.S. Senate petition—compared to this, he calls his time with Cogbill “cordial.”

Hunt’s emailed statement explains that after her team found no evidence that “election law [was undermined], we withdrew our challenge." On March 29, Cogbill secured his place on the ballot for the May primary next month.

With 49 days left until the primary, Cogbill, the comeback kid, was back on track.

Cogbill's upbringing and organizing career underscore every inch of his policy agenda. He doesn’t quite have “top issues,” because there are so many improvements that Philadelphians need, but he speaks at length about firearms and labor rights. Midway through the conversation, Cogbill launches into an analysis of Pennsylvania’s gun legislation, policies with which he’s intimately familiar from his work with CeaseFirePA. He is also a gun violence survivor–"I have been robbed, shot at, and lost a friend in the same year," Cogbill says. He explains loopholes for domestic abusers, the most dangerous and accessible types of firearms, and ways people equip their weapons to maximize harm. At the time of this article’s publication, Cogbill is the only Gun Sense candidate supported by Moms Demand Action in the state.

He’s especially invested in the intersection of education and labor movements. Cogbill champions a $25 minimum wage, the golden number that allowed his mother to provide for him as a child. He also approaches student debt with a pragmatic, working–class mindset. He thinks the government should cancel student debt, but “a lot of people in the 3rd [District] don’t have student debt because they haven’t even fathomed the thought of higher education, let alone finishing high school.” If elected, he would work to cancel not only student loans, but also utility debt or financial burdens that impact low–income individuals.

Cogbill recognizes that education is not always an equalizer, especially where he’s from. While he was able to snag a coveted job at the AFL–CIO, he’s seen his friends with college degrees rejected from the building trades.

“A lot of his policies are statistically backed, but are also rooted in thinking of humanity and the greater good,” says Adam Leghzaouni, an intern on Cogbill’s campaign and first–year student at Drexel University.

Cogbill knocked on the door of Adam’s family business, a meat market near Cheltenham, when he was collecting signatures in February. Adam joined the campaign to help with social media and build a base of youth volunteers. He admires Cogbill’s community–centered policies and his “charismatic, genuinely kind” personality.

“He’s a breath of fresh air,” Adam says, “just something that you hope to have in the U.S. Congress.”

Even so, Cogbill continues to face challenges when going against the status quo. He says that Bass, the aunt who inspired his commitment to social impact, does not support his campaign for Congress—endorsing the more established candidate Evans. This doesn’t phase Cogbill; he's fine charting his own path.

“I'm gonna count on my community and not the establishment to get me over the hump,” Cogbill promises. “If the establishment wants to support me, I'll take [it] and I'll be grateful for it, but I think everybody has to know and everybody has to be aware that I'm going to side with my neighborhood every single time.”

Shrugging on his coat, Cogbill says he's excited for a publication run by young people to be the first to tell his story. Crossing Starbucks’ threshold onto Walnut Street, he continues onto Penn’s campus. He’s going to take a quick photo, he says.

Two days later, Cogbill posts on Instagram. It's an image of him posed in front of Brick House, Simone Leigh’s tribute to Black beauty. Snow dots his curious winter coat–camo pants–sneakers combo, and a smile spans the width of his face. “Made by a Black woman, raised by Black women…” the caption reads. It’s all of the authenticity, tenacity, desperation, and love of his campaign wrapped into one photo. And it’s extraordinary.