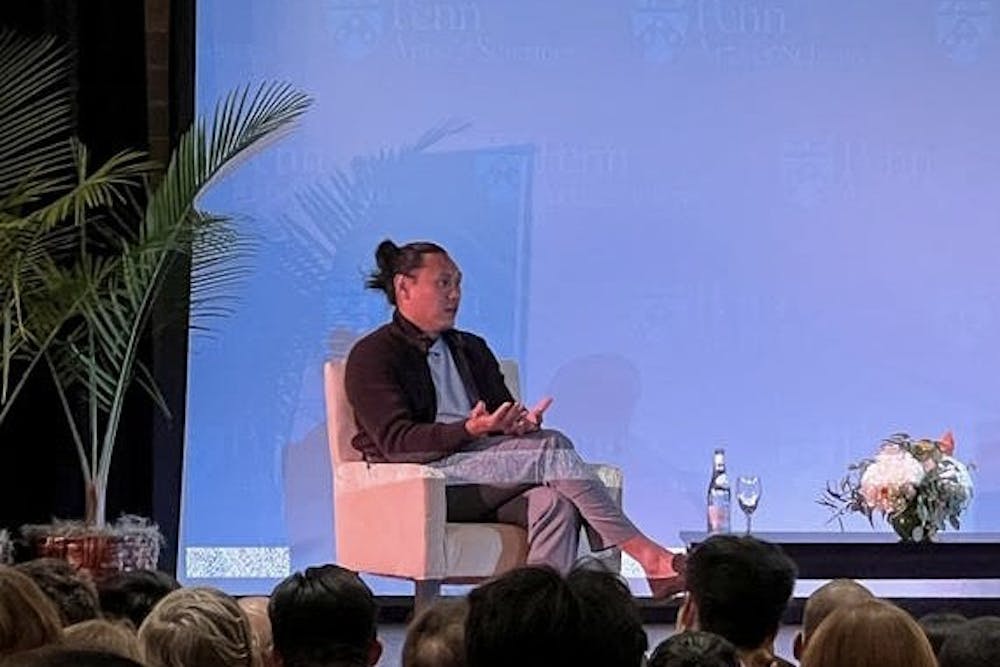

An hour before Penn’s Crazy Determined Asians: Jon M. Chu and the Power of Representation event began, the emerald–tiled Harrison Auditorium was silent with its green velvet seats entirely empty. Then suddenly, as if the great and powerful Oz himself had appeared, murmurs and conversations immediately rose with the arrival of a certain individual. At that moment, Jon M. Chu entered the room and began to admire the space’s grandeur and beauty.

“I was just looking out here and it looks like very Wicked colors,” Chu grinned as he referenced his forthcoming film, Wicked—Universal Pictures’ film adaptation of the Broadway show—starring Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo.

Chu, at his core, is a curious storyteller, who loves to be immersed in people’s heritage and culture. Hollywood can be a brutal industry, but this hasn’t fazed Chu, who remains a genuine, passionate, and down–to–earth filmmaker.

Before there was Hollywood Jon M. Chu, director of the cultural phenomenon Crazy Rich Asians, In the Heights, Now You See Me 2, Justin Bieber: Never Say Never, two Step Up movies, and the upcoming Wicked, there was film student Jon M. Chu. As a student at the University of Southern California, Chu was given the opportunity to refine his filmmaking skills after spending his childhood in Los Altos, Calif. editing and filming movies for his friends and family. While Chu might be best known for directing films that celebrate diverse cultures, like Crazy Rich Asians, which, when released, was the first major Hollywood picture with an all–Asian cast in 25 years, Chu started off his professional career by avoiding stories that were personal to him. He admits that “in a weird way, [he] was rewarded for not doing [films] about [his] own heritage.”

In college, Chu watched a student’s short film about a girl’s dating habits where the final joke was her slamming the door on a man simply because he’s Asian; at this point, the whole audience, except for Chu, erupted with laughter. The joke didn’t connect with Chu because being Asian was not a joke to him—it was part of his identity. In response, he made a short called Gwai Lo: The Little Foreigner, a musical about an Asian American man torn between what his family and friends want him to be, which included personal experiences from Chu’s life growing up Asian American. But after insecurities over the film’s message, Chu never submitted Gwai Lo to film festivals. It would be over a decade before he directed another film that connected to his own roots: Crazy Rich Asians.

In recent years, there has been a “Jon M. Chu effect,” where Chu’s films like Crazy Rich Asians and In the Heights have become a launching pad for actors of color—including Awkwafina, Henry Golding, Gemma Chan, Constance Wu, Anthony Ramos, Melissa Barrera, Leslie Grace, and many other talented performers—to become leads in dozens of new projects. Chu’s championing of representation allowed these actors to be cast and have the spotlight to shine.

Here are edited excerpts from 34th Street’s conversation with Jon M. Chu.

JP: What helped you make the jump into making more personal stories that are rooted in family and heritage like In the Heights and Crazy Rich Asians, after previously avoiding those topics in college and your earlier films, including Gwai Lo, which you chose not to submit anywhere?

JMC: It was a long journey. In college you’re very idealistic and naive to the world. I made Gwai Lo which means “white devil” in Chinese, and that’s what they called me when I went to Hong Kong for the first time, where everyone looks like you and you start to feel like, ‘Oh wow, they treat me like I’m family.’ But then at the same time, they’ll call you "Gwai Lo" because you’re not from there, either. In film school, you shoot and show your dailies to your class, and even the comments from my class where I was one of probably three Asians, people would question parts [in Gwai Lo] when people would call me names. And these comments questioned my experiences, as if I was overreacting or had too much victimization. When we showed Gwai Lo, it got a great reception. But I felt very sensitive about what I was saying in it. So I buried it and instead made another short called When the Kids Are Away about the secret life of mothers which had nothing to do with being Asian and that was the one that got me into the business [after Steven Spielberg watched it].

After doing Now You See Me 2, I just felt like, ‘What am I doing here? Anyone could have made this movie, and it didn’t have to be me.’ So I went back to the things that I felt scared to talk about, and of course, it goes back to when I was in college and it was my Asian identity. It just so happens that this book [Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians] that my family was reading was both commercial and had flowery, fun things. But at the core was Rachel Chu which was very much what Gwai Lo was based on.

JP: Why did you sign up to do In the Heights and how was casting similar to Crazy Rich Asians, where you tried to find undiscovered or underappreciated talent?

JMC: I signed up for In the Heights before [Crazy Rich Asians] because it spoke to this immigrant family community that I very much grew up in, even though it wasn’t Latino or wasn’t in Washington Heights. I understood that Lin[–Manuel Miranda] had this amazing ability for making his stories very universal, so getting into that story felt like we could do it again, and so rather than find the typical Latin stars, we went to go search for the ones that could rise, and for people like Leslie Grace and Melissa Barrera and Anthony Ramos, it just gave them a platform to do that.

JP: I am very jealous that you know Lin–Manuel Miranda, as I’m one of his biggest fans. What is he really like?

JMC: He’s amazing and is just a kind person. He acts the exact same way off and on camera. You should meet him.

JP: Well, it’s a little tough to meet him, he’s a little busy right now.

JMC: [Laughs] Yes, that’s true.

JP: How was it like filming on location for projects like In the Heights in Washington Heights and Crazy Rich Asians in Malaysia and Singapore versus filming in a studio, which I’m assuming will be where Wicked is primarily shot?

JMC: Yes, we’re not going to Oz. When we shot Crazy Rich Asians, being in Singapore really dictated the look and allowed me time to learn about the style, and so I knew for In the Heights, we had to do it in Washington Heights. It was also the idea of, how do you take a Broadway show about a block and make it real? Lin wrote that music in the language of those blocks in rap and hip–hop and in all of the different styles and it was all around us as we framed our shots. We’re in Washington Heights, so where can we point the camera to?

JP: Many of your movies include food sequences, including the dumpling scene in Crazy Rich Asians and the dinner scene in In the Heights. How is food an aspect of storytelling, especially since you grew up around your parents’ restaurant, Chef Chu’s?

JMC: Food was so naturally a part of my life. I was around food and that’s how my parents communicated their love for me. When you basically live at a restaurant, you tell stories to customers who are learning about our family, and so I see [the restaurant] as a house of stories. In these movies, you have a great opportunity to show off a culture’s food and make it look delicious, instead of exotic and strange.

JP: In any film, you need to edit scenes. But for a movie musical, especially an adaptation of a Broadway musical, you must also need to cut entire songs out, which you did for In the Heights. How do you choose what songs to keep in the final version, as you look toward Wicked, which I assume you will need to cut some songs from. Or maybe not?

JMC: You never know, you never know. In a way, In the Heights was easier to translate because it’s not built like a movie, it’s very much a slice of life. It was also way too long, but it was almost like a buffet, finding scenes that moved me the most and then defining an order, which for me was Usnavi at the center, telling this story about his neighborhood to his children. That was our center, and anything that does not have to do with that is not needed.

JP: What is the preproduction for movies like Wicked and In the Heights which has years of preparation prior to the actual filming?

JMC: Well, for something like Wicked, it’s years, and I think they’ve been working on [Wicked] for 15 years, and I have just come on in this last year. You also got to shoot when you’re ready, and for me and Lin, it was about getting to know each other, and Quiara [Alegría Hudes, writer of In the Heights] and I had to break the script many times before we found the right combination. By the time we’re making the movie, I know what is important to everybody.

JP: Finally, In the Heights has moments of spectacle, but the story is very grounded in the community of Washington Heights, centered on Usnavi’s life and dreams. What was the importance of having the spectacle aspects and smaller character moments tied together?

JMC: I wanted to paint what it feels like to be a dreamer in a community because that’s what I relate to so much. I grew up in a Chinese restaurant [Chef Chu’s], and my dreams were so beautiful and so much bigger than my town, and I know talking to Lin and Quiara that that was their experience as well. When you are the child of immigrants and [your family’s] dreams and hopes are pretty high, you dream big, so we needed to visually show that. I wanted to give as much grace and elegance to people’s dreams and to the dreams of their parents and grandparents than any movie musical does for its characters.