“Are bookstores even a thing anymore?” says my Social Psychology professor, apropos of nothing, in the middle of a lecture on social cognition. Long gone are the days of couches in Barnes & Noble and Kanye West rapping “we met at Borders.” Even further in the rearview mirror is a distant era when a romantic comedy like You’ve Got Mail could be powered by the David and Goliath struggle between a mega chain bookseller and a beloved, independent local bookstore. Maybe that’s because it feels like Goliath wins every time.

In 2020, retail bookstores made up only around 34% of the $25 billion of books sold that year. And according to the American Booksellers Association, more than one independent bookstore closed each week at the beginning of of the COVID–19 pandemic. These are astronomical losses for the communities that grew within and around the havens that bookstores create. And Philadelphia is no stranger to these casualties. In June of 2020, we lost People’s Books & Culture, and just last month, Center City’s beloved Joseph Bookshop sold its last book after 70 years.

In spite of these inhospitable conditions, for every bookstore we’ve lost, another remains—or has even sprung up out of the ground to take its place. Philadelphia’s share of radical, feminist, and queer bookstores spans decades—old institutions and modern incarnations that evade being labeled as “bookstores” at all, but they share the same ethos—and reckon with the same challenges—when it comes to supporting, educating, and invigorating anyone who steps foot inside.

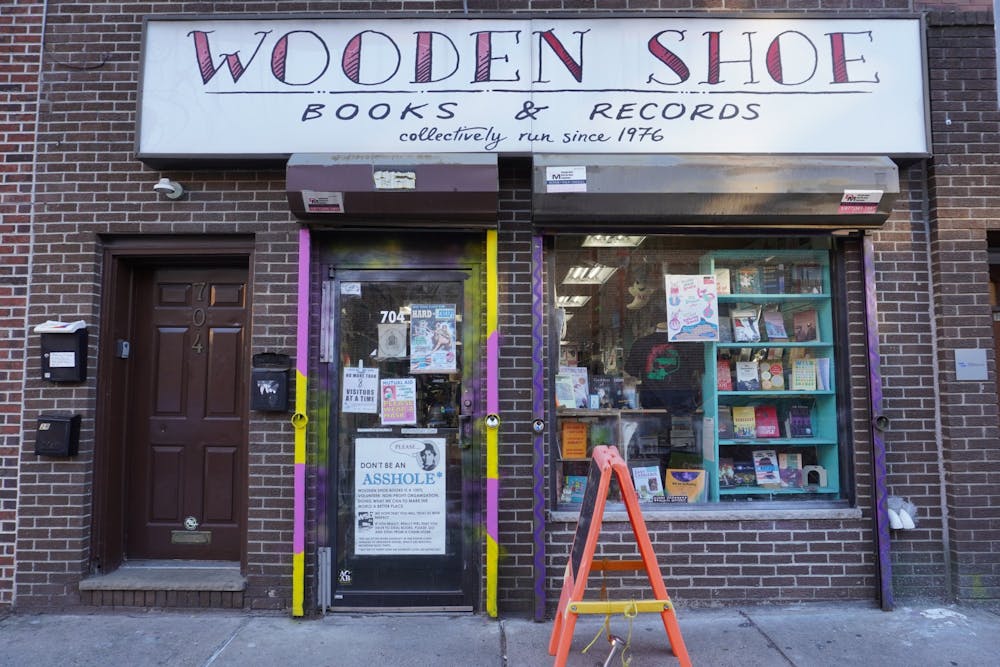

Giovanni’s Room, Philly’s destination queer and feminist bookstore, and Wooden Shoe Books, which specializes in radical literature, have both stuck around for some 50–odd years, and are deeply enmeshed in their respective corners of the city. Meanwhile, their newcomer counterparts, like Making Worlds Bookstore and Social Center and Harriett’s Bookshop, are pushing into districts that may be more or less receptive to their ideologies. These are all bookstores, but the role they serve in their communities—the buildings, blocks, neighborhoods, and city they occupy—goes far beyond just selling books.

Katharine Milon is plenty familiar with having the significance of her work disputed or disregarded. During our conversation, Milon, a manager at Giovanni’s Room, which is right on the border of Philadelphia’s Gayborhood, describes a customer who came into the store that past Sunday: “He looked me straight in the face and said, ‘Do you really think people need gay bookstores anymore? I wouldn’t think they needed them anymore because it’s become so mainstream.’” Milon was incredulous. She grew up in the Washington, D.C. area, where she hung around Dupont Circle and the now–shuttered LGBTQ bookstore Lambda Rising—experiences fundamental to her queer adolescence.

Milon grasps that “It’s hard to explain the importance of physical spaces to people who are either not used to them or [who] are so used to them that they don’t question them at all.” But Giovanni’s Room and other brick–and–mortar bookstores are important precisely because of the physical space that they occupy. They pay rent. They’re part of a neighborhood. They have doors you can open, chairs you can sit in, and rooms you can have conversations in.

It’s hard to think of a bookstore that’s more entrenched and integral to the fabric of Philadelphia’s queer subculture than Giovanni’s Room. A brief trolley ride from Penn, it happens to be the oldest queer and feminist bookstore in the country.

But it’s been a hard road keeping it around for almost half a century—the bookstore wouldn’t exist today if not for an intervention from another city staple.

Alan Chelak, another of the bookstore’s managers, was working at Philly AIDS Thrift when Giovanni’s Room announced, in 2014, that it would be shuttering its doors. Rather than let this happen, Philly AIDS acquired Giovanni’s Room. “It was kind of a no–brainer. Everybody was like, ‘Let’s do this, this makes sense. We have to save this place,’” says Chelak.

That thrift store mentality has permeated the way the bookstore operates. The store sells a combination of new and used queer books, some that get sent in by long–time patrons and others that have been around since before the store’s acquisition—still marked with their original Giovanni’s Room stickers.

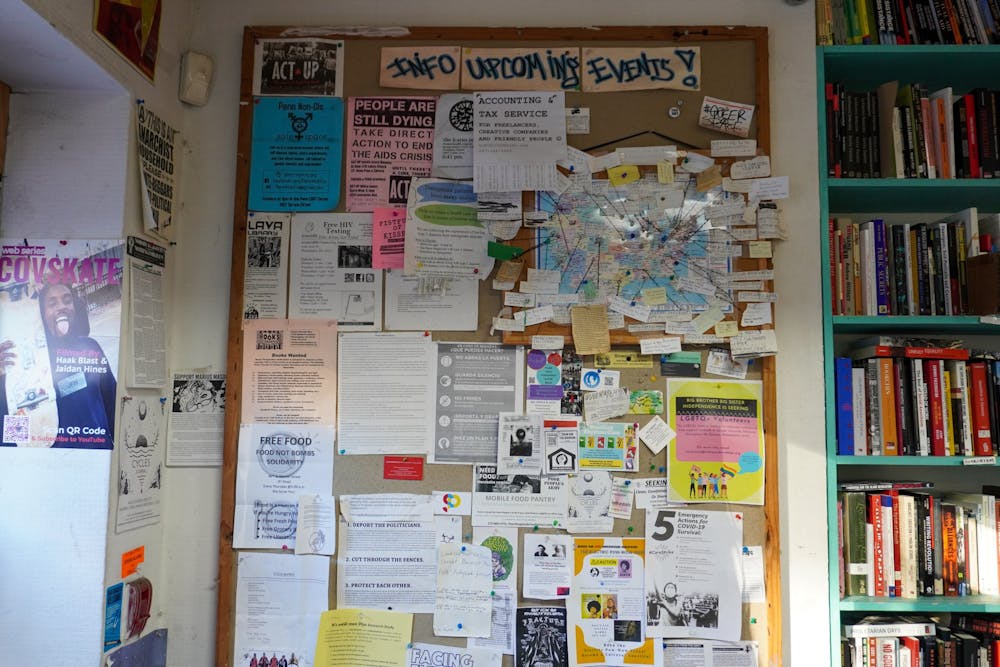

These stickers are not the only relics of the bookstore’s past. The walls are practically plastered with layers of old flyers, posters, and even graffiti that immortalize decades of queer activism in the city.

“Have you ever heard the word 'hauntology'?” Milon asks, eyes glimmering inquisitively behind her glasses. It’s the best word she’s found to capture the bookstore’s spirit, and she double–checks online to make sure she’s getting the definition right:

Hauntology

haunt·ol·o·gy \ ‘hȯnt-ˈä-lə-jē \

1 : “a range of ideas referring to the return or persistence of elements from the social or cultural past, as in the manner of a ghost.”

Nothing exemplifies Giovanni’s Room’s haunted quality better than the God of WordStock, a computer that’s at least a decade older than I am, and which resides in the store’s third–floor office. It runs on a tape and doesn’t even have a mouse, so the staff have to learn all the keyboard commands, but it also contains a running database of every LGBTQ book published since the late 1980s up to those that will be published six months into the future.

The risk of revolutionary literature is the ease with which it can be lost—from changing social values or simply the passing of time—when it only reaches a small group of people. With that in mind, a repository of books that exist at the margins, like the God of WordStock, is worth its weight in gold. More so, it’s proof that stores like this carry more history than can be obtained from just the pages on the shelves.

If there’s anyone who understands the challenge of keeping radical thought alive, it’s Carl Craft, co–founder of Wooden Shoe. “The Shoe,” as it’s referred to colloquially, is a collectively–run anarchist bookstore that opened in 1976. The store has always placed a premium on physical space, which is hard to find within anarchist organizing. A group of dissatisfied libertarian socialists, anarchists, and radical feminists originally conceived of the Shoe as a means of consolidating published anarchist materials into one location. Its aims have always been political first and literary second.

Craft recognizes the irony of this. “It’s funny, in one sense, the contradiction of being an anarchist, libertarian–left project that’s anticapitalist but has to swim in the ocean of capitalist retail,” he says. Craft laments the Shoe’s obligation to major wholesale book retailers like Ingram, which require they mark up the titles sold in the store by “200, 300—even 500%.” Craft adds that, “You have to live with contradictions of what you think should be done with books, information, [and] knowledge” on one hand, “and knowledge as a saleable commodity” on the other. Although he can laugh it off, there’s a palpable sadness when the best way to accomplish your political goals requires compromising them.

Both Giovanni’s Room and Wooden Shoe have become indispensable parts of their neighborhoods, which in turn have taught them how to best be of service. Gender, race, and sexual politics are all represented among the Shoe’s shelves, and that’s in large part because devoted employees and patrons curate their content. “If you’re a small, independent book retailer, you don’t have to go to a corporate office to get approval to buy anything,” says Craft. Their catalogs are in the hands of the community, not a corporation.

Will Clark, another manager at Giovanni’s Room, also notes how the store’s patrons influence the books they order. “There are people, literally, who will come in and have a list of books,” he says, “and they’ll say, ‘You should get these.’”

During my conversation with Craft, I observe a similar process at the Shoe—a customer comes into the store looking for a book they don’t have in stock. Before she leaves, Craft takes down the book’s title and author, making sure to spell everything correctly. He plans to order it, making sure that “Out of Darkness, Shining Light by Petina Gappah—G–A–P–P–A–H” will be available to anyone who comes in, whether they’re looking for it or not.

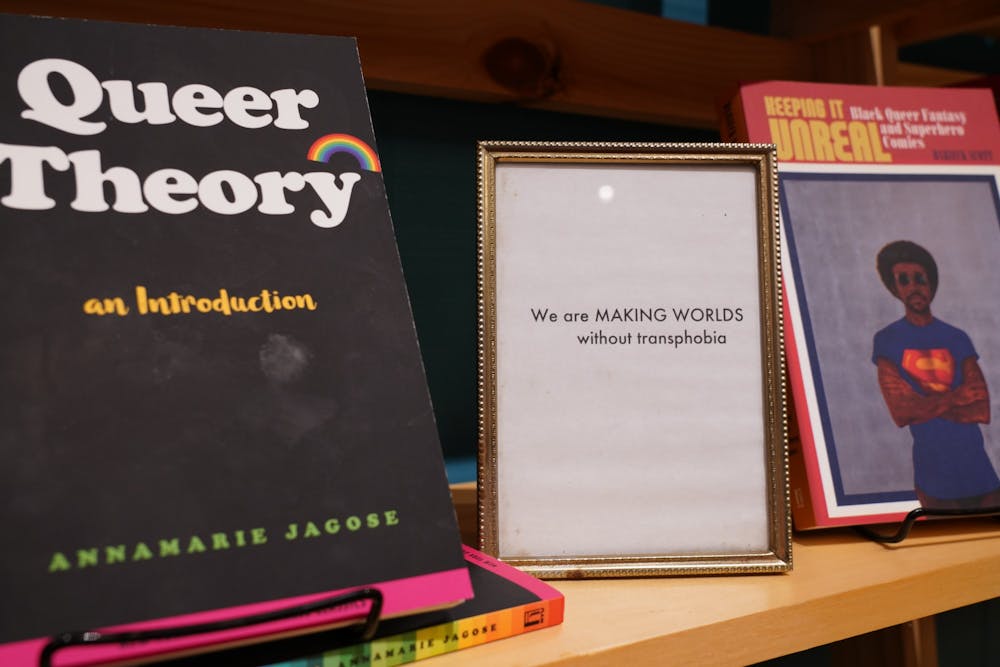

Jaskiran Dhillon represents the two sides of this reciprocity—she is both a curator and community member. Dhillon has been a resident of West Philadelphia for over 12 years, and now she works at Making Worlds, located at 45th and Walnut, as part of its co–op model. Making Worlds opened its doors on Valentine’s Day of 2020 as an extension of the publishing house called Common Notions, just one month before the COVID–19 pandemic forced the fledgling business to recalibrate its operations.

Both Dhillon, a Penn alum, and founder Malav Kanuga, an Annenberg School for Communication postdoctoral fellow, are reluctant to throw around that label of “bookstore,” and for good reason: Making Worlds has always extended beyond that humble premise. Dhillon is reluctant to box it in, arguing that spaces like this have the potential to be so much more than bookstores. They can “be a space where people find a set of encounters and access to conversations and experiences that allow them to continue learning, but also to bring things that they care about to the center of a neighborhood conversation.”

But Making Worlds is still a place where books are sold, and Kanuga plays a significant curatorial role in choosing which ones, largely focusing on those published by Common Notions as well as other “independent and movement–related publications,” end up in its display window. “We are all already carrying multiple worlds of experience, through largely the contradictions of how we’ve arrived at who we are,” says Kanuga. The books themselves are really just “openings to being able to read more fully and connect to a sense of your own imagination.”

Most importantly, Making Worlds has a meaningful presence in its neighborhood; it serves as a center point where community members can congregate. The shop is within walking distance of Penn, but there’s also a vast expanse of West Philadelphia beyond it—enough to house robust, flourishing West African, Vietnamese, and Laotian communities, to name only a few. Making Worlds is situated at a locus where many different ethnic, social, and cultural worlds intersect and overlap.

But what if you’re a Black business owner making inroads into a predominantly white neighborhood?

“How did I end up outside a protest handing out books?” That’s Jeannine A. Cook, sounding somewhat incredulous at her own anecdote. Cook is the founder of Harriett’s Bookshop, located on Girard Avenue in Fishtown, which is overwhelmingly white and one of Philly’s most gentrified neighborhoods.

As an undergraduate student, Cook started selling books from a stand at the corner of Broad and Cecil B. Moore, right next to Temple University. From our conversation, Cook’s DIY determinism and ability to galvanize those around her is obvious. “Sometimes if you want to get something done you just have to get it done yourself,” she says, and “Books have been a huge part of my ability to do that.”

Both Harriett’s and its sister store, Ida’s Bookshop, celebrate women authors, artists, and activists—their names come from Harriet Tubman and Ida B. Wells, respectively. In that sense, Harriett’s isn't so much “haunted” by things as it is haunted by people: Black women who have irrevocably changed the course of history but haven’t gotten their historical due. Cook situates herself in the lineage of these women: “Books have this incredible ability to help us time travel—reading helps us to read ourselves,” she says.

In the summer of 2020, at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests in Philadelphia and other cities around the country, Cook revitalized this practice. Instead of bringing signs, Cook and company brought books, a “guerrilla–style” act. Harriett’s’ activism doesn’t just exist within the confines of its storefront. “A lot of things have happened behind closed doors—behind four walls—for far too long,” says Cook. She’s made a commitment to reaching out to her community, whether that’s through handing out books at protests, or through Harriett’s’ soapbox reading series, which takes place in a circle on the sidewalk at the corner of Marlborough and Girard.

Why do we read? We read to learn about ourselves, about our world, and about our identities, particularly for those of us who can’t experience them—in all their nuance and complexity—through mainstream cultural representation. A cynically minded individual might say that any of this could be easily accessed online, but anyone who’s worked at—or even spent time in—a radical, feminist, or queer bookstore would be wary of that claim.

Ever the wordsmith, Cook warns of “keyboard gangsters” who spread misinformation and create ignorance. Will Clark, from Giovanni’s Room, puts it even more bluntly: “The internet’s a shitty place to learn things. I mean, it’s a good place to learn things. But honestly, in my opinion—I’m not a fucking Luddite or anything—but it doesn’t provide an environment.”

Entering a bookstore is completely free from commitment. You can walk into a place like Giovanni’s or Harriett’s without letting it define anything about who you are, other than a willingness to learn and expose yourself to new ideas. The accessibility of these bookstores—where all you have to do is open a door and step inside—plays a big part in that. Clark sums it up nicely when he says, “This is the nature of a bookstore: It’s a casual space, anyone can go in.”

But sometimes taking the first step into one of these spaces can be a really big deal. Milon paints a picture of people’s whole bodies “lighting up” upon entering the store, and Chelak, also from Giovanni’s Room, reaffirms this. “You can tell that crossing the threshold of the door is a really big, important moment for them. They’re excited to be able to find books about people like them or for people like them,” says Chelak. These bookstores allow young people to have profound experiences of their queer identities—of seeing and being seen.

Giovanni’s Room facilitates those experiences, and it’s nothing short of miraculous. I asked every person I interviewed why they thought it was so important that feminist, radical, and queer local, independent bookstores exist—each answer they gave was different, but interconnected.

Carl Craft of Wooden Shoe says they offer people an opportunity to put their money where their politics are, while Making Worlds’ Malav Kanuga emphasizes the importance of actually occupying buildings, asking questions like, “Who does the city belong to, brick by brick, neighborhood by neighborhood?”

For her part, Jeannine A. Cook fashioned Harriett’s Bookstore as an antithesis to institutional racism, trying to build an institution of her own that was based on the values of freedom and liberation.

But it’s Alan Chelak’s answer that’s perhaps the most viscerally compelling: “Why not? We’re allowed to. You gonna stop me? You're gonna stop all of these people from doing this?”

Giovanni’s Room cribs its name from a novel by James Baldwin, but it’s another Baldwin quote—this one from a 1963 Life Magazine profile—that best encapsulates why radical bookstores are so essential to the people that step through their doors. Back in the dusty, cluttered third–floor office, the same one that houses the God of WordStock, Katharine Milon opens up her laptop and reads it aloud to me: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”