There’s no denying it: It’s been a rough year. From lockdown blues, to stateside political upheavals, to an escalating climate crisis, we’ve had to learn to weather the challenges as they come. In the face of all this gloominess and uncertainty, it’s no wonder that so much recent academic research has a pessimistic bent. The past year has seen a spate of research on darker subjects like death, decay, illness, and depression by prominent scholars—all against the backdrop of recent trends towards doomsaying and reactionary rhetoric in and outside of academia. Pundits all across the board sound the death knell for democracy, civil liberties, and even basic human decency. Whoever you listen to, one thing is clear: the world as we know it is ending. But in the current moment of dystopian thinking, one scholar’s work stands apart from the crowd.

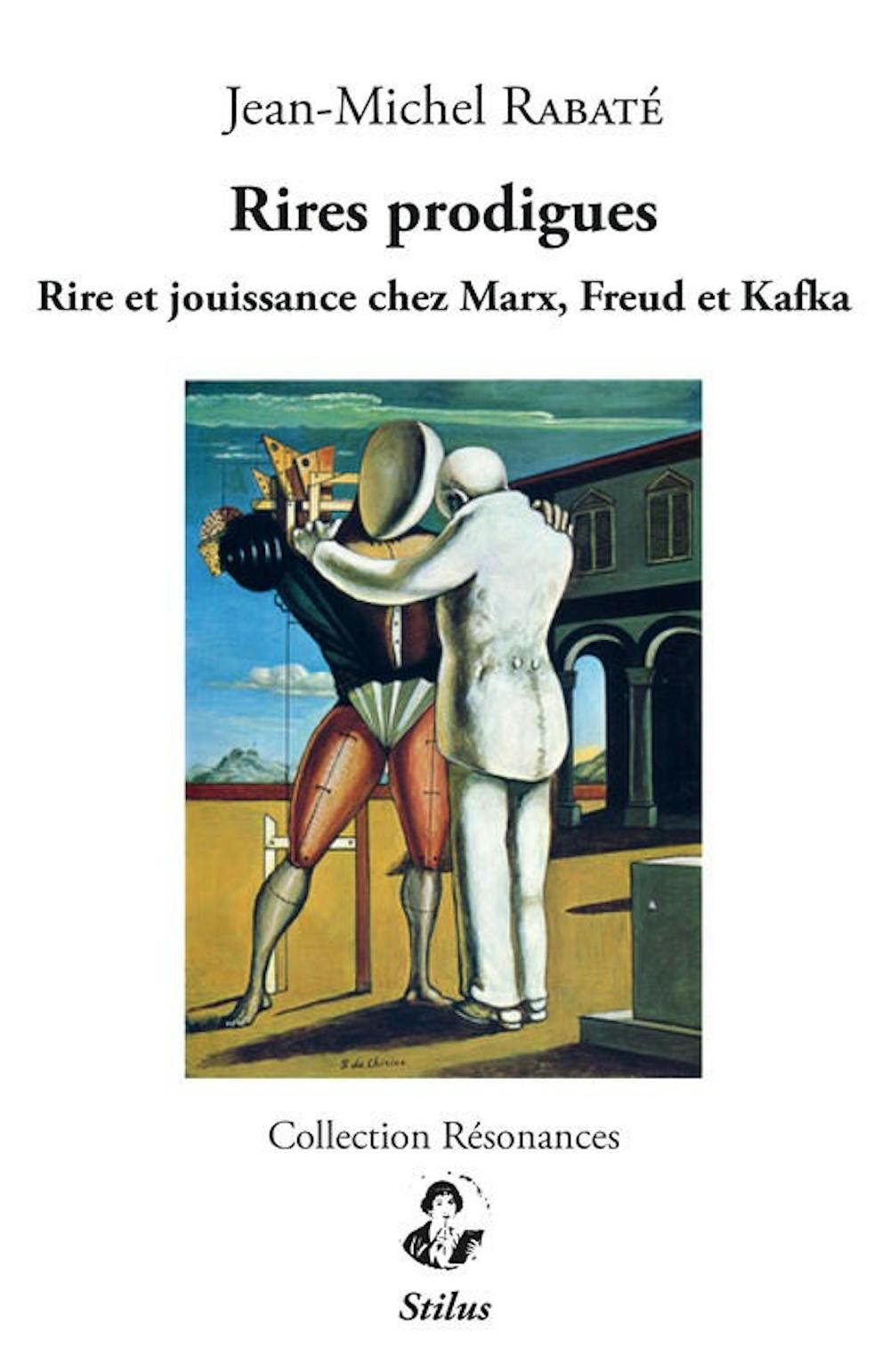

Enter Jean–Michel Rabaté, a professor in Penn’s Department of English and Comparative Literature. Rabaté’s bibliography runs the gamut from a comparative study on Beckett and Sade to an excavation of the term “modernity” and all its implications—but it’s his most recent book, a monograph on laughter, that really stands out. In Rires Prodigues: Rire et Jouissance chez Marx, Freud et Kafka (in English, that’s Prodigal Laughter: Laughter and Delight in Marx, Freud, and Kafka), Rabaté offers an irreverent take on the title’s intellectual heavyweights.

For a book that concerns itself with laughter, the tone is fittingly irreverent throughout. While Rabaté tackles his subjects by way of Lacan, Lacan himself is spared no jest. In fact, Rabaté opens with a delicious jab at the famed philosopher: “I will make a confession: oftentimes, Lacan made me laugh when I attended his lectures.” So Lacan, famously obtuse to the point of absurdity, could be funny—et alors?

In fact, the barb goes deep—Rabaté states that most of Lacan’s funniness was inadvertent, a result of his notorious tendency towards obfuscation. But the punchline here is that his students either failed to remark the obfuscations or dismissed them out of hand. Rabaté goes so far as to conjure the image of the rapt students sitting beside him, who followed teach’s every word with “serious, intense, devoted enthusiasm.” Rabaté pulls no punches here, eagerly interrogating the philosopher’s legacy. But if the book, in all its cheekiness, seems like a perfectly–of–the–moment antidote to all the pessimism and fear-mongering of 2021, rest assured that it’s been in the works for a long time.

Rires Prodigues emerges on the heels of what Rabaté views as a troubling trend in academia: scholars’ and students’ inability to laugh. “These days,” Rabaté says, “people are afraid to laugh and afraid to make statements that could trigger laughter because it’s felt as if laughter could too quickly aggravate, antagonize.” Whether this fear of laughter arises from reverence for the canon, fear of authority, or a simple instinct towards self-preservation matters little. Whatever its root, Rabaté finds this tendency problematic, not least because it goes against the natural instinct towards laughter. “Teachers are afraid of making jokes. Students are afraid of laughing. And I think this is not very healthy,” he says.

And in the world of humanities academia, laughter keeps the machine running—it’s at the root of every scholarly breakthrough. Without a willingness to poke the bear, there’s simply no way to move beyond conventional wisdom, no way to bring fresh takes to an age-old discipline. Rabaté, both as a teacher and a researcher, takes this willingness to break with the canon to heart. On paper, he’s attached to the English department, but his unique approach involves a blend of disciplines, including philosophy, psychoanalysis, and sociology—all key ingredients in his creative vocation. But it’s not just professional creativity at stake: our ability to learn also depends on our willingness to laugh.

Laughter, at its core, means taking a hammer to old wisdom and applying your own perspective to established ideas. It means going beyond a superficial understanding of a given text. It means actively inserting yourself into the issue at hand. Rabaté sees this as the key to engaging with old guard thinkers, Freud among them. It’s why the controversial thinker, often ridiculed in popular conversation, still resonates so deeply with his students. “He talks to certain situations like trauma, exclusion, racism”—issues that weigh heavily on students’ minds. It’s easy to make fun of ideas like the Oedipus complex or penis envy, but laughter doesn’t happen without a little reflection, and reflection drives us to learn.

Beyond the humanities bubble, there are broader stakes here. Jokes, with all their subversive potential, are powerful political acts. “It can be dangerous,” Rabaté says. But within that danger lies great possibility: to inspire, to reform, to revolutionize. Assuredly, there’s a line between reactionary jokes and progressive ones—but the challenge of distinguishing between them is all the harder if we aren’t willing to joke in the first place. So how can we free ourselves to laugh, at ourselves if nothing else?

Self–irony, like any virtue, takes practice. We might take a few cues from an unexpected maestro, Lacan himself. Rabaté witnessed firsthand the philosopher’s reaction when a student radical attempted to humiliate him. The key takeaways? Keep your composure. Turn the tables on the humiliator—revel in the embarrassment. Besides, there’s a certain unity in laughter and tears, as Rabaté sees it.

“Often,” he says, “you think you love because you are sort of happy, sunny, on the side of pleasure or enjoyment. And you cry if you are sad or melancholy.” But Rabaté challenges this way of thinking, arguing in Rires Prodigues that excessive enjoyment eventually amounts to suffering. And conversely, we so often laugh to relieve suffering, to cope with all our daily miseries. A key lesson emerges: to function in our ailing society, we must learn to weld the negative and positive tendencies together into one. Especially so in 2022. In the wake of the pandemic, we need laughter more than ever.